Assessing FY 2026 Appropriations

Without further appropriations, the federal government faces a partial government shutdown on January 30 as the continuing resolution (CR) funding nine of the 12 annual appropriations bills for Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 expires. With the discretionary spending caps from the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 now expired, Congress faces few limits on how much to appropriate. Nonetheless, Congress should ensure that any funding package reduces rather than increases the debt by appropriating at responsible levels, avoiding costly add-ons, and capping future discretionary spending levels.

In this piece, we explain that:

- A one-year freeze to discretionary spending could save about $350 billion over a decade. A ten-year freeze would save $1.5 trillion.

- Congress should reduce total funding to below current spending levels, while passing full-year appropriations for FY 2026.

- Additional spending increases are particularly unnecessary in light of the $382 billion appropriated by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and potential DOGE savings.

- Any funding bill should focus on appropriations and avoid extraneous spending or tax-cut measures – particularly without offsets.

- Congress should also renew discretionary spending caps in order to impose limits on appropriations, control spending growth, and reduce projected deficits.

Congress Should Appropriate Below Current Levels

Congress has not passed all 12 appropriations bills since March 2024 and has largely been operating under CRs – which essentially extend past funding – since then.

In November 2025, following the longest government shutdown in modern history, Congress enacted three of the 12 appropriations bills – for Agriculture, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction-Veterans Affairs (MilCon-VA) – and funded the remaining nine bills through a CR in effect through January 30, 2026.

Taken together, these bills result in annualized spending of $1.653 trillion for FY 2026 – $10 billion above comparable FY 2025 levels of $1.643 trillion.1

Lawmakers should not allow another wasteful government shutdown, nor should they continue to fund the government with stop-gap CRs. But with the deficit projected to total nearly $2 trillion this fiscal year and debt expected to pass 102% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), lawmakers should work to reduce rather than increase total funding levels.

Three additional bills that were recently announced by bipartisan, bicameral appropriations leadership (and already passed in the House) – for Commerce-Justice-Science, Energy-Water, and Interior-Environment – would reduce spending levels by nearly $4 billion from FY 2025. And an additional two bills announced this week (and passed in the House) – for Financial Services and National Security-State – would further reduce spending levels by nearly $10 billion. On net, this leaves FY 2026 spending levels modestly below adjusted FY 2025 nominal levels,2 so long as additional appropriations bills are set at or below FY 2025 levels.

Comparing Potential Appropriations Levels

| Budget Authority, Billions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriations Bill | FY 2025 Full-Year CR |

FY 2026 Minibus-CR |

FY 2026 Minibuses + CR for Remainder |

| Agriculture | $26.6 | $26.7 | $26.7 |

| Commerce-Justice-Science | $79.3* | $78.4 | $78.0 |

| Defense | $831.5 | $834.4 | $834.4 |

| Energy-Water | $58.1 | $57.9 | $58.0 |

| Financial Services | $26.1* | $26.3 | $26.3 |

| Homeland Security | $65.0 | $65.0 | $65.0 |

| Interior-Environment | $40.9 | $40.3 | $38.6 |

| Labor-HHS-Education | $208.2* | $207.8 | $207.8 |

| Legislative Branch | $6.7 | $7.2 | $7.2 |

| Military Construction-Veterans Affairs | $146.6 | $153.3 | $153.3 |

| National Security-State | $59.3* | $59.8 | $50.0 |

| Transportation-HUD | $94.4* | $95.8 | $95.8 |

| Total, Base Funding | $1,642.6 | $1,652.9 | $1,641.2 |

| Memo: | |||

| Nondefense | $750.1 | $755.2 | $742.6 |

| Defense | $892.5 | $897.6 | $898.5 |

Sources: CRFB analysis of CBO estimates, House & Senate Appropriations Committee documents, and legislation.

*Amounts for FY 2025 funding have been adjusted to include funding from FRA ‘side deals’ for apples-to-apples comparison but do not account for other Changes in Mandatory Programs (CHIMPs).

Unfortunately, there will be pressure to increase spending in these other areas. For example, the recently enacted National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2026 authorized $856 billion for Department of Defense programs – $21 billion above a CR level. Additionally, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed to increase the Transportation-Housing and Urban Development bill by nearly $5 billion above a CR level. Lawmakers should resist this pressure and instead identify areas to reduce spending levels.

Additional Spending Is Unnecessary in Light of OBBBA and DOGE

Although Congress usually increases nominal appropriations year over year – often to keep pace with inflation – such increases are particularly unnecessary when considering the recent cash infusion Congress provided to many agencies and reduced personnel costs many agencies now face.

We estimate the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) funded about $382 billion of mandatory appropriations to agencies normally funded by the discretionary appropriations process. This includes $153 billion of Armed Services funding, $133 billion of Homeland Security funding, $39 billion for Immigration and Law Enforcement, and over $50 billion of additional funding. Nearly all of that funding must be obligated by the end of FY 2029. Importantly, OBBBA borrowed to appropriate these funds and, in fact, added roughly $4.1 trillion to the debt overall.

Mandatory Appropriations in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

| Spending Category | Budget Authority |

|---|---|

| Armed Services | $153 billion |

| Homeland Security | $133 billion |

| Immigration & Law Enforcement | $39 billion |

| Coast Guard | $25 billion |

| Air Traffic Control | $13 billion |

| Space Exploration | $10 billion |

| Other Mandatory Appropriations | $10 billion |

| Total | $382 billion |

Source: CBO estimate of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act as enacted. Note: figures may not sum due to rounding. Does not include appropriations normally authorized by the Farm Bill.

Importantly, not all of this new funding can directly replace defense and nondefense discretionary appropriations – some is allocated for specific new (and in some cases one-time) initiatives that would not have been covered by appropriations. But clearly, much of the funding could be used to cover otherwise-expected cost increases.

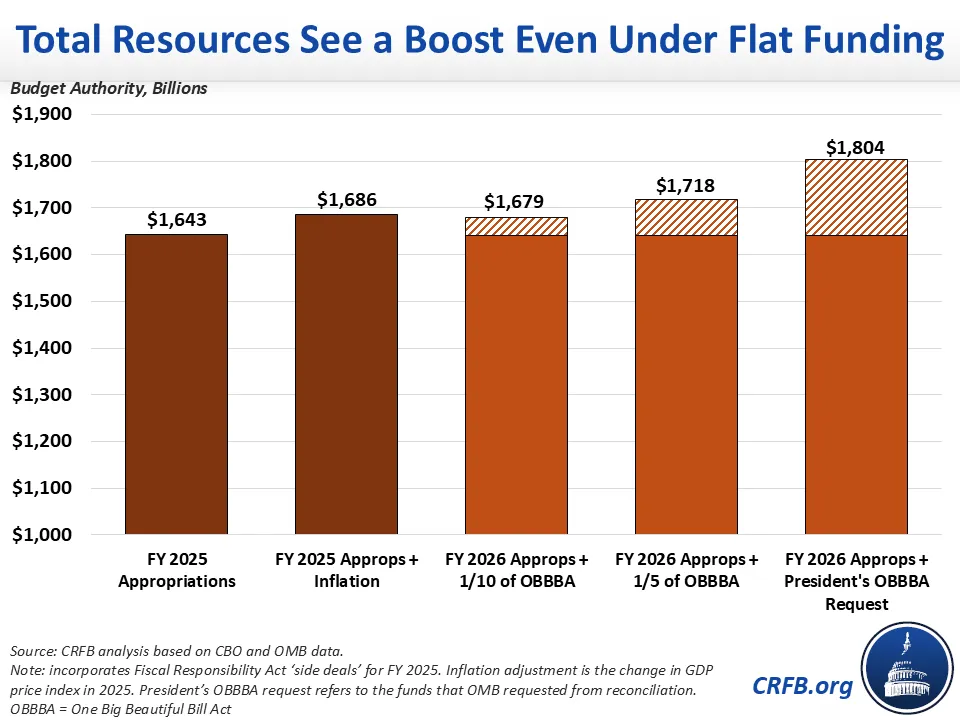

Indeed, the President’s discretionary budget request asked that more than $160 billion of OBBBA funds be used to support base discretionary funding in FY 2026, including nearly $120 billion on the defense side. With appropriations funding kept at current levels, this would result in a 10% increase from FY 2025.

Assuming instead that only one-fifth of the funds are used to support base discretionary funding, total appropriations would still rise by 5%. Even if only a tenth of the funds could backfill base appropriations, spending would rise roughly with inflation. This is true for both defense and nondefense funding.

Actions stemming from the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) – tasked with reducing overall spending – should also make lower spending levels even easier to enact. Although DOGE’s claimed savings from cuts to contracts and grants appear to be significantly overstated, their efforts (and companion OMB and agency efforts) appear to have resulted in roughly a 10% reduction in the size of the civilian government workforce. This could allow for $20 billion or more of spending cuts.

In light of the DOGE savings and OBBBA spending, policymakers have significant room to reduce both defense and nondefense appropriations levels. At the very least, they should be able to appropriate at FY 2025 levels, spending below the current CR.

Funding Bill Should be Clean and Costless

In addition to avoiding any discretionary spending increases, policymakers should resist calls to couple an appropriations bill with new mandatory spending or tax cuts – particularly without offsets.

All too often, what begins as a bill to fund the government and prevent a shutdown transforms into “Christmas-Tree” legislation, loaded up with extraneous and sometimes costly measures. In the FY 2020 funding bill, for example, Congress added more than $500 billion to the debt largely from repealing several taxes enacted to finance the Affordable Care Act.

Some examples of policies that lawmakers may be considering or may try to attach to full-year appropriations this year include:

- Extension of the enhanced Affordable Care Act subsidies

- Expansions of Health Savings Accounts

- Repeal of savings in the reconciliation bill

- Tariff repeals, rebates, or bailouts

- Extensions or modifications to tax cuts, such as changes to the gambling loss deduction or extending the temporary tax cuts enacted in OBBBA (no tax on tips and overtime, etc.)

These policies could add tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars to a debt that is already on track to surpass its record within three years. Rather than considering costly add-ons, Congress should pass clean appropriations or – if necessary – a clean CR. If any additional measures are included, they should be fully paid for – ideally twice over.

Lawmakers Should Restore Discretionary Spending Caps

In addition to agreeing upon responsible spending levels for FY 2026, Congress should restore multi-year discretionary funding caps going forward.

Appropriations levels have been subject to spending caps for 12 of the last 14 fiscal years – from 2012 through 2021 and then 2024 and 2025 – as well as throughout most of the 1990s. Throughout these periods – and especially earlier in the caps regimes – discretionary spending growth was meaningfully constrained and deficits were lower than they would have been without the caps.

For example, prior to the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011, discretionary spending had grown by about 8% per year from 2007 through 2010, whereas discretionary spending was essentially flat from 2012 through 2017. When Congress wanted to increase spending above the cap levels, bipartisan agreements offset the entirety of the cost for 2014 and 2015 and about half the cost of modest increases in 2016 and 2017.

Two further budget cap deals – the Bipartisan Budget Acts (BBA) of 2018 and 2019, respectively – raised the caps for 2018 through 2021. Unfortunately, BBA 2018 offset about a quarter of its costs, while BBA 2019 offset less than a fifth of its direct costs and a very small portion of its total costs including the effect on the discretionary baseline.

After two years of no caps – FY 2022 and 2023 – Congress renewed caps for 2024 and 2025 via the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. Those caps, after accounting for various side agreements that altered their effective savings, resulted in about $1 trillion of deficit reduction over a decade (even after accounting for the changes from the full-year FY 2025 CR).

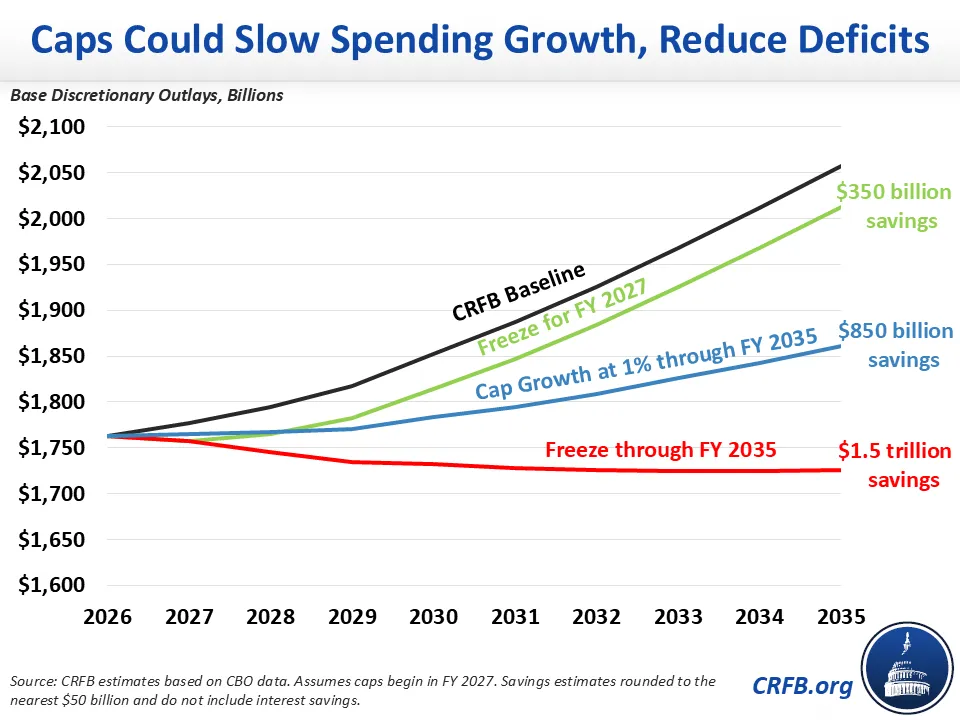

Given the high and rising national debt, Congress should once again employ discretionary spending caps to reduce deficits. Compared to the CRFB discretionary baseline, we estimate that funding the government at the current proposed levels for FY 2026 (minibuses enacted and a CR for the remainder) and freezing that funding for one year could save about $350 billion, freezing it through 2031 could save more than $1.2 trillion, and freezing it through 2035 could save $1.5 trillion. Even capping and limiting spending growth to 1% for the rest of the decade could save more than $850 billion. Importantly, actual savings may differ against CBO’s forthcoming baseline, which is expected next month.

Potential Discretionary Cap Options

| Cap Option | Ten-Year Savings |

|---|---|

| Freeze for FY 2027, then inflation | $350 billion |

| Freeze through FY 2029, then inflation | $850 billion |

| Freeze through FY 2031, then inflation | $1.2 trillion |

| Freeze through FY 2035 | $1.5 trillion |

| 1% Growth through FY 2029, then inflation | $500 billion |

| 1% Growth through FY 2031, then inflation | $700 billion |

| 1% Growth through FY 2035 | $850 billion |

Source: CRFB estimates. Savings are against CRFB baseline, which is a similar to but may differ from the CBO baseline. Savings do not include interest savings and are rounded to the nearest $50 billion.

Going forward, lawmakers should prepare well in advance of future-year appropriations by agreeing to multiyear overall funding caps for both defense and nondefense discretionary spending. These caps should reduce deficits by either freezing, cutting, or capping appropriations growth below the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline convention, which assumes that discretionary spending grows roughly with inflation annually. Discretionary spending caps give appropriators the certainty of a topline funding level while requiring them to pay for any increases above the caps.

***

With deficits on course to average more than $2 trillion per year over the next decade, interest spending on the national debt topping $1 trillion annually, and debt projected to reach a new record within three years, Congress should not add any further to borrowing through increases in discretionary spending. Policymakers should agree to flat funding this year and cap future year appropriations with renewed discretionary spending caps.

1 The entirety of the appropriated increase for the enacted bills can be explained by MilCon-VA bill, which has some of its veterans health funding appropriated a year in advance (so the FY 2026 funding was already appropriated in FY 2025). The minibus enacted in November actually reduced MilCon-VA below the amount that a “clean” CR from FY 2025 levels would have, while the Agriculture and Legislative Branch bills each got slight boosts above FY 2025 levels.

2 For an apples-to-apples comparison, we adjust FY 2025 appropriations to include the increased BA that was offset by funding rescissions to the IRS and Commerce Department and the emergency-designated spending for base needs, which were also considered ‘side deals’ agreed to as part of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. Without those adjustments, FY 2026 funding would be about 2.5% larger than FY 2025 so far.