Pell Grant Program Faces Serious and Immediate Shortfall

The Pell Grant program will end 2026 in the red and faces a cumulative 10-year shortfall exceeding $100 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) February 2026 baseline. Without Congressional intervention, this could lead to a disruption in full Pell award in the 2028-2029 school year.

CBO’s projection of the 10-year Pell shortfall is even higher than CRFB’s projections from December, which already showed a large shortfall. Using data from CBO, we find:

- The Pell program is projected to be $5 billion underwater by the end of this fiscal year, despite a one-time injection of $10.5 billion from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA).

- Without Congressional intervention, students may not receive their full Pell award amounts starting in the 2028-2029 school year.

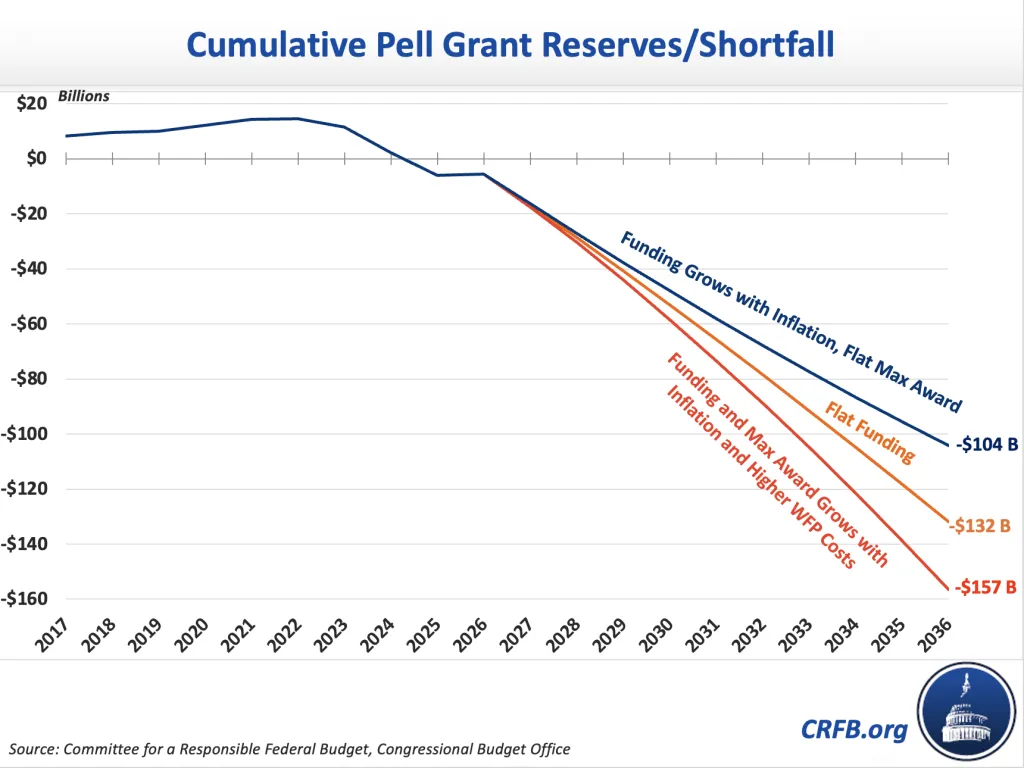

- Over the next decade, the Pell program faces a $104 billion to $132 billion cumulative shortfall, under CBO’s projections and assumptions.

- This shortfall could grow to $157 billion under our alternative assumptions.

The cost of Pell Grants has risen dramatically since Congress modified the award formula in 2020 and failed to adequately fund the new expansion, and has grown more due to expanded eligibility to short-term workforce programs ("Workforce Pell").

With the Pell reserves on the verge of depletion – despite a one-time cash injection – Congress can no longer delay action and should work to permanently fix the structural shortfall in the Pell Grant program.

Pell Costs Continue to Exceed Funding

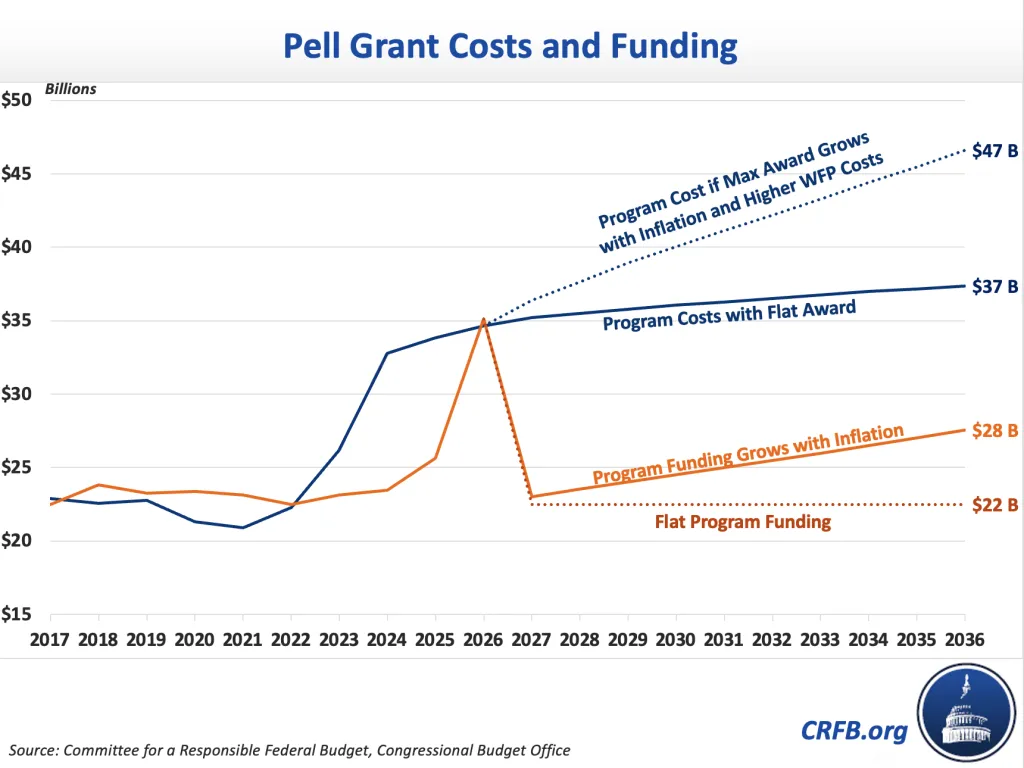

The cost of the Pell Grants program has grown significantly in recent years, from $21 billion in 2021 to a projected $35 billion in 2026, and CBO estimated it will further grow to $37 billion by 2036 assuming a flat maximum award. Meanwhile, annual funding is less than $24 billion this year, resulting in a projected deficit of over $11 billion 2026, when one-time fundings is excluded.

With inflation-indexed funding, CBO projects this shortfall will trend toward $9 billion by 2036 and total $104 billion over the next decade.

However, in recent years Congress has kept nominal funding levels flat for the Pell program. If they continue to do so, CBO projects the annual shortfall will grow to $14 billion by 2036, and total $132 billion over the decade.

Even these scenarios may be optimistic, however. If Congress continues to increase the maximum award with inflation (historically it has increased by at least that much, on average) and Workforce Pell enrollment grows faster than projected, even if funding grows with inflation, the Pell deficits will grow to $18 billion by 2036 and the ten-year shortfall would total $157 billion.

History also suggests that when new eligibility is created, enrollment often exceeds initial projections. expanded Pell eligibility to short-term workforce programs. While proponents argue this will help workers gain credentials for in-demand jobs, it comes at a fiscal cost. CBO estimates Workforce Pell will add roughly $2 billion to program costs over the next decade. However, we believe actual costs could be up to $7 billion depending on take-up rates, how states and institutions implement the new program, and how the Department of Education interprets and enforces the accountability measures in the law.

If Congress fails to increase funding or decrease costs to match the shortfall, the Department of Education would eventually run out of cash and need to proportionally cut everyone’s Pell Grant award to the point where it could pay out for that year. The last time Congress faced this sort of sustained shortfall, a mix of increased funding, new eligibility limits, and the elimination of a newly passed expansion to Pell worked to fill the shortfall.

Policymakers Must Address the Pell Shortfall To Avoid a Disruption in Benefits

The Pell Grant program is already projected to be in shortfall by the end of FY 2026, which means that students could see cuts to their Pell Grant by school-year 2028-2029. If a shortfall exists, then the Department of Education could run out of cash by the middle of the following school year and be forced to proportionally reduce students’ awards. Congress has also created rules that make it extremely costly for them to ignore the problem for more than one year of shortfall. The problem could be even more severe if CBO’s projections for the current fiscal year turn out to be too low (CBO has underestimated the cost of the end of each fiscal year since 2023).

While Congress could try to kick the can down the road once more by merely filling the shortfall this year, because costs are higher than funding for every year moving forward, this crisis will continue to occur every year until a more fundamental change to the cost and funding of the Pell Grant program is found.

To reduce the cost of the Pell Grants program, some options include: tightening eligibility based on income, enrollment status, or the cost of the program; tying the award to academic progress; eliminating the mandatory add on or reducing award amounts for some or all recipients. The Department of Education can also play a role in controlling costs by ensuring that Workforce Pell is held to the highest accountability standards possible under the law to keep out and kick out underperforming programs.

Alternatively or additionally, Congress could increase funding for the Pell grant program – either by boosting discretionary appropriations and providing mandatory appropriations. Either approach should include offsets – on an annual basis in the case of discretionary spending and over a decade without use of timing gimmicks for mandatory appropriations.

A number of potential offsets exist within the higher education space. Over a decade, eliminating the in-school interest subsidy on some undergraduate loans would save $15 to $20 billion, limiting or eliminating the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program would save $10 to $20 billion, and clarifying that the President cannot unilaterally cancel debt could save over $20 billion. Reducing higher education tax credits could also save around $130 billion over 10 years.

Congress chose to increase the cost of the Pell Grant program back in 2020 without paying for it, and has since ignored many opportunities to fix the problem, despite knowing about the looming shortfall. Now the bill has come due, and the late notices can no longer be ignored.