It's Time for "Super PAYGO"

“Pay-As-You-Go” or PAYGO rules and laws require offsets for new tax cuts and mandatory spending so they do not add to the debt.1 Too often these requirements are ignored with Congress voting to waive its own PAYGO rules and either delay or cancel the sequestration cuts triggered by the statutory PAYGO law. Given their importance for helping to keep the fiscal situation from deteriorating, existing PAYGO rules and laws need to be strengthened by making them harder to waive and altering the sequestration process to make it more politically achievable.

But even then, conventional PAYGO merely keeps the fiscal situation from deteriorating; it does nothing to make it better. Meanwhile, every dollar of revenue or savings used to pay for new initiatives is no longer available for much-needed deficit reduction. That’s why we need a new form of PAYGO – a “Super PAYGO.”

The concept of Super PAYGO was first introduced by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget in 2007 and was recently discussed by Harvard economist Jason Furman in a chapter of the book Strengthening America’s Economic Dynamism. Under Super PAYGO, every dollar of new spending or tax cuts would be offset by at least two dollars of revenue increases or spending reductions, thus ensuring that new tax cut and mandatory spending legislation also includes deficit reduction.

So, for example, if lawmakers wish to enact a $100 billion spending program, they would need to identify at least $200 billion in tax increases or spending cuts. New initiatives would be both paid for and coupled with deficit reduction.

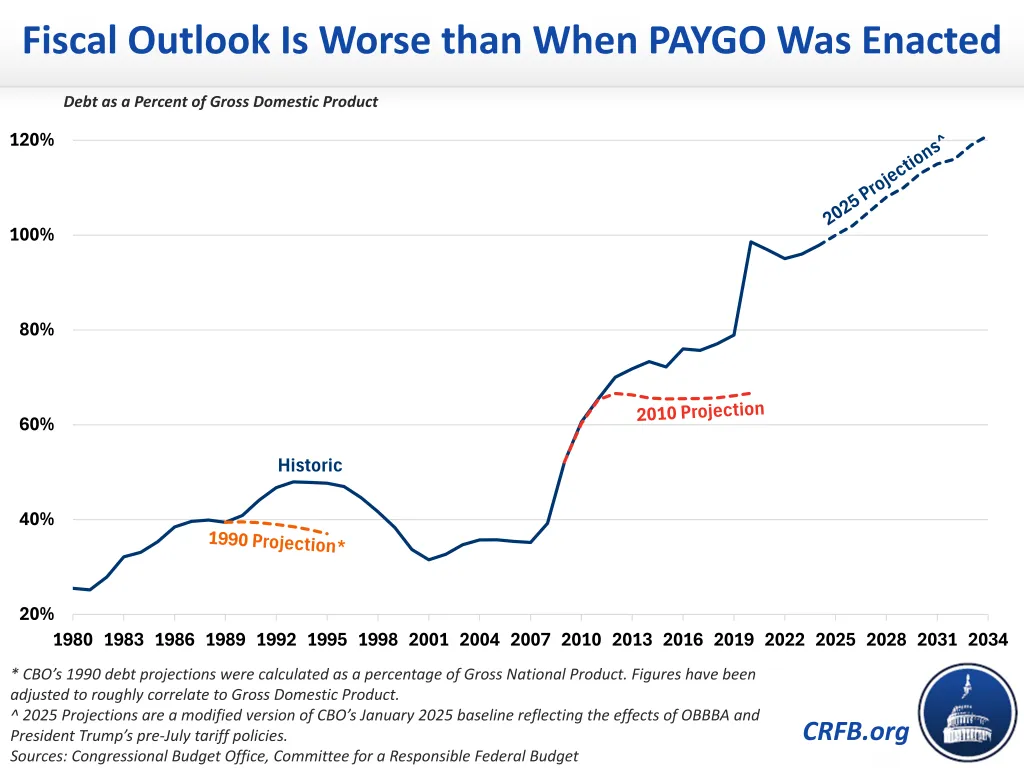

The need for a more aggressive form of PAYGO is clear when considering our current fiscal trajectory. In 1990, when statutory PAYGO was first enacted, our national debt was roughly 40 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and projected to remain stable. In 2010, when statutory PAYGO was reintroduced, debt was roughly 60 percent of GDP and growing slowly. Today, debt is nearly 100 percent of GDP and rising rapidly.

The need for Super PAYGO isn’t just about our worsened fiscal trajectory; it’s also about the need to start using offsets to actually reduce deficits instead of just paying for (or partially paying for) new spending or tax cuts. Simply stabilizing debt at 100 percent of GDP over the next decade would mean reducing projected deficits by nearly $10 trillion, which would require a 12 percent increase in projected revenues or an 11 percent cut in projected primary spending.

There are trillions of dollars in thoughtful offsets available to lawmakers, but using them to offset new spending or tax cuts means they’re no longer available for actual deficit reduction. For example, the OBBBA included roughly $2.5 trillion in offsets, yet the law will ultimately increase debt by more than $4 trillion. Those $2.5 trillion in offsets are now no longer available for deficit reduction because they were used in a bill that will increase deficits. What’s more, since lawmakers naturally tend to employ the more politically feasible deficit reduction options first, the ones left over that are still available for deficit reduction tend to be more difficult politically and therefore less likely to become law.

As the old saying goes, “the first step in climbing out of a hole is to stop digging.” By preventing lawmakers from increasing debt, abiding by PAYGO helps accomplish that first step, but it does nothing to compel lawmakers to take the second and more difficult step of actually climbing out of the hole of debt we’ve dug for ourselves. That’s why we need Super PAYGO. Of course, changes to the budget process and enforcement are not a panacea for fixing the debt or a replacement for political will. Ultimately, lawmakers must be willing to make the tough decisions needed to put us on a more fiscally responsible path. Nonetheless, Super PAYGO or other reforms can help create a better environment for fiscal responsibly.

1 There are four distinct types of PAYGO rules and laws: Statutory PAYGO, PAYGO rules in the House and Senate, CUTGO rules, and Administrative PAYGO. Statutory PAYGO requires that, over the course of the year, legislation maintains or reduces current law deficits over the coming five and ten fiscal years. PAYGO Rules require that any increases in mandatory spending or tax cuts be fully offset in order for legislation to be considered on the House or Senate floors. CUTGO rules are similar to PAYGO rules, except they do not require tax cuts to be offset and do not count tax increases as offsets. Administrative PAYGO is similar to Statutory PAYGO, except it applies to executive actions instead of legislation. PAYGO and CUTGO rules in the House and Senate are enforced through a point of order against considering legislation in violation of the rule. Statutory and Administrative PAYGO are enforced through a broad spending cut to certain mandatory spending programs known as “sequestration”, which is triggered if there is a positive balance on the PAYGO scorecard at the end of the year. Several federal programs are exempt from these cuts, including Social Security, veterans’ programs, low-income entitlement programs, and discretionary spending programs. The current iteration of Statutory PAYGO has been in effect since 2010, while Administrative PAYGO is much newer, having been enacted in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. The Senate’s PAYGO rule has been in effect more-or-less continuously since 1993. The House initially adopted its PAYGO rule in 2007, then switched to CUTGO from 2011 to 2019, when it switched back to PAYGO, which is currently in effect.