An Economic Sugar High Doesn’t Mean Sustained Growth

The recently-enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) is expected to significantly boost near-term economic activity, but is unlikely to accelerate the long-term growth rate. While the combination of temporary stimulus and a one-time boost in work and investment may meaningfully accelerate the growth rate in 2026 and 2027, it is unlikely to have a sustained effect on growth – and may even slow long-term growth as a result of additional borrowing. The U.S. economy experienced a similar temporary boost in output after the passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) and Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA18).

In this piece, we show:

- OBBBA is likely to boost near-term output, but will have little sustained effect on the economic growth rate over time.

- Estimates find OBBBA will increase near-term output by nearly 1 percent due to a temporary increase in demand and one-time boost to labor and capital supply.

- Much or all of the near-term economic impact will fade as stimulus wears off and higher debt crowds out investment and slows long-term growth.

- TCJA and BBA18 lead to a similar temporary boost in economic activity.

How Will OBBBA Impact Growth?

The recently enacted reconciliation law, OBBBA, extended or revived and expanded large parts of the 2017 TCJA and introduced new tax cuts and spending, while offsetting some of the costs with spending reductions and new revenue (see a full summary here).

Supporters of OBBBA have argued that it will significantly accelerate economic growth. Along with other policies, some have said OBBBA could boost the sustained real growth rate over the next decade from below 2 percent, (as projected by the Congressional Budget Office and Federal Reserve) to 2.6 percent, 3 percent, or perhaps much higher.

OBBBA is indeed likely to boost near-term economic growth – particularly in 2026 and 2027. But it is unlikely to have a large impact on sustained economic growth.

OBBBA is likely to influence economic output in several ways. Specifically, we expect it will:

- Boost demand and generate near-term stimulus by increasing borrowing by an average of nearly $600 billion per year from 2026 through 2028.

- Boost labor supply by reducing taxes on work and reducing certain means-tested benefits.

- Boost capital supply by expanding investment tax breaks and reducing taxes on certain business income.

- Shrink labor supply by reducing net immigration as a result of additional border and immigration funding and less generous benefits for immigrants.

- Shrink capital supply by increasing debt by $4.1 trillion through 2034, crowding out investment.

At least in the near-term, the positive effects of OBBBA on demand, labor, and capital will almost certainly outweigh the negative effects. However, the stimulus effect from higher demand should only be temporary and will fade as the economy adjusts (and may fade particularly quickly if the economy remains close to full employment).

Meanwhile, the boost to labor and capital are likely to represent a one-time increase in the size of the economy rather than a sustained increase in the growth rate. At the same time, the effects of increased borrowing and reduced immigration are likely to ramp up over time and put downward pressure on long-term growth.

As a result, what may appear as a boost to the growth rate in the next couple years will likely resemble a “sugar high” that will be difficult to maintain absent huge (and largely unrelated) boosts to underlying productivity.

Estimating OBBBA’s Economic Effect

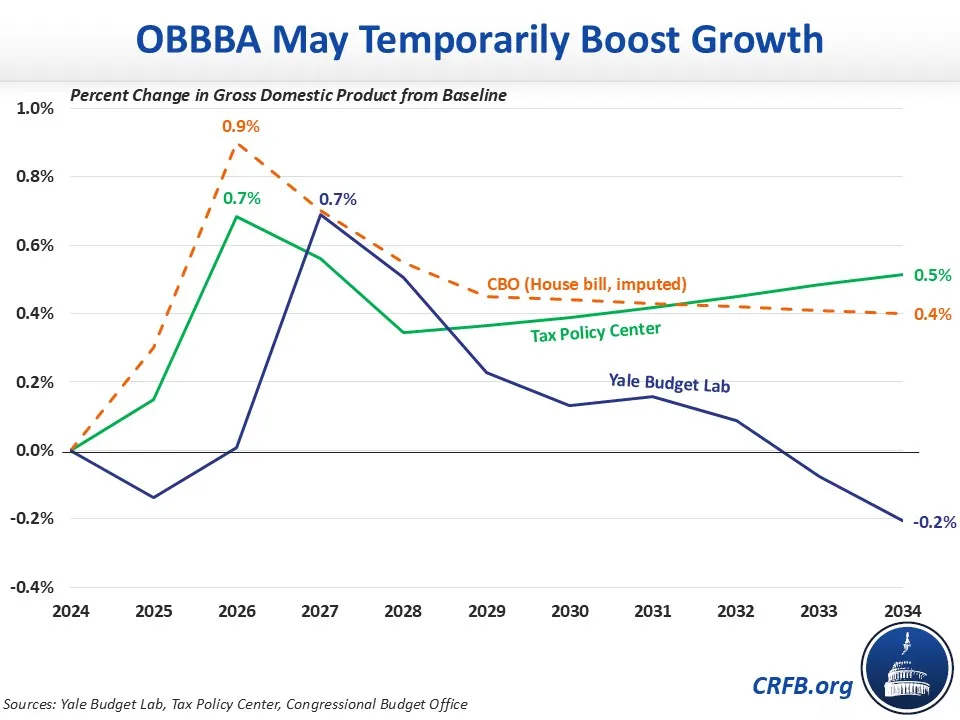

Modelled estimates of OBBBA’s economic impact confirm that the law’s positive influence on growth is likely to be short lived.

The Tax Policy Center estimates OBBBA will boost the level of economic output by 0.7 percent in 2026 alone, falling to 0.3 percent in 2028 and rising to 0.5 percent by 2034. Their estimates imply OBBBA will increase the 2026 growth rate by 0.5 percentage points, slow growth by almost 0.2 percentage points per year from 2027 to 2028, and then boost the growth rate by 0.03 percentage points on average per year thereafter.

Yale Budget Lab also estimates OBBBA will increase near-term output by 0.7 percent – albeit in 2027 instead of 2026 – but finds it will reduce output by 0.2 percent by 2034. Yale Budget Lab’s estimate implies OBBBA will increase 2027 growth by 0.7 percent but then slow the growth rate by more than 0.1 percent on average from 2028 through 2034.

And although CBO has not estimated the final legislation, its dynamic score of an earlier House version found that the bill would boost output by 0.9 percent in 2026, falling to 0.4 percent by 2034. While CBO does not provide year-by-year estimates, the numbers imply a significant boost in the growth rate through 2026, a significant reduction in the next few years, and little change between 2029 and 2034.

Other estimators such as Tax Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and Penn-Wharton Budget Model do not present estimates of the near-term stimulative effects of OBBBA, though they find a similarly modest impact on the long-term growth rate. On the high end, Tax Foundation estimates output would increase 1.25 percent in 2034, while on the low end Penn Wharton Budget Model estimates output would decrease by 0.2 percent.

The White House’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) expects much more robust growth, but also a similar pattern. CEA expects a near-term stimulus boost of nearly 2.4 percent and a 4.75 percent increase in GDP in 2028, falling to 2.55 percent by 2034.

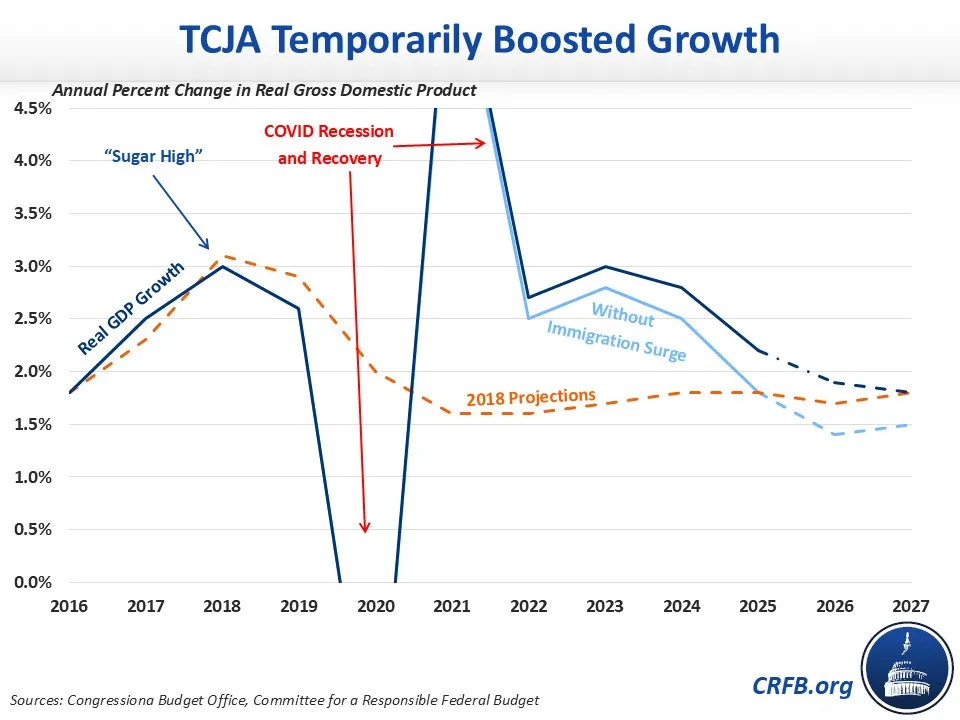

The TCJA Sugar High

Expectations of strong economic growth after OBBBA likely stem, at least in part, from the robust economic growth the U.S. economy enjoyed after the passage of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act. But that growth, too, appears to have represented a one-time boost to economic activity rather than a sustained increase in the rate of economic growth.

In early 2018, CBO estimated that the combination of lower taxes on work and investment, as well as stimulus from borrowing under the TCJA and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 would boost the economic growth rate to 3.0 percent in 2018 and 2.9 percent in 2019, before falling to 2.0 percent in 2020. Roughly as expected, the economy grew by 3.0 percent in 2018 and 2.6 percent in 2019 – and appeared on course to grow at about 2.2 percent in 2020.

Of course, the COVID pandemic and response instead led to a massive contraction and expansion that was completely unrelated to the TCJA. But on average, GDP has grown by about 2.3 percent per year since 2019. The growth rate would have been 2.1 percent if not for the unexpected surge in immigration (which increased the labor force).

To be sure, it is impossible to know the exact long-term effect of the TCJA on the economy. However, CBO’s initial estimates found it would boost output by a peak 1 percent in 2022 and by slightly less thereafter, and recent research suggests the actual effects are broadly consistent with this initial estimate.

* * *

Reducing taxes on labor and capital can lead to a one-time boost in economic output. Borrowing to do so can cause an additional temporary surge in demand. This "sugar high" will ultimately fade, leaving a debt hangover to slowly erode the pace of economic growth.

To boost incomes and put the debt on a more sustainable path, policymakers should work to identify reforms to expand output and boost long-term economic growth. Key to this agenda is thoughtful tax, regulatory, and entitlement reforms. Perhaps most importantly, is a plan to put the national debt on a more sustainable path.