The CRFB Fiscal Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation

The United States faces numerous economic and fiscal challenges, including surging inflation, rising interest rates, trust funds heading toward insolvency, a broken budget process, and an unsustainably rising national debt.

In order to help the Federal Reserve fight inflation, reduce interest costs, and support economic growth, policymakers should put forward a plan to put the national debt on a sustainable long-term path. Though there is no one single “correct” fiscal metric, the higher the debt-to-Gross-Domestic-Product (GDP) ratio and its growth trajectory, the more vulnerable the U.S. economy is.

Ideally, debt should be gradually reduced to its half-century historical average of about 50 percent of GDP. Given political constraints, we suggest at least stabilizing the debt at its current level within a decade, requiring roughly $7 trillion in savings.

There is no single correct way to achieve this goal, though any comprehensive plan should stabilize and reduce debt as a share of the economy, support the Federal Reserve’s efforts to fight inflation, secure trust fund solvency, promote long-term economic and income growth, and improve fairness and efficiency in government.

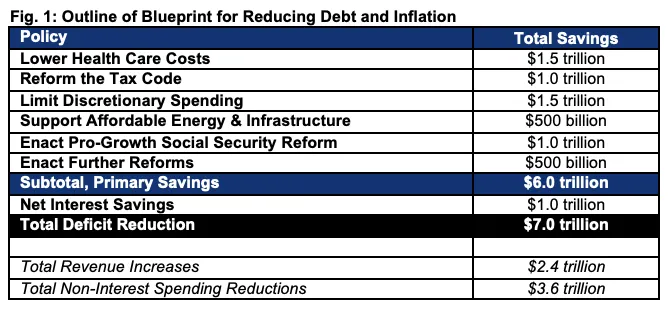

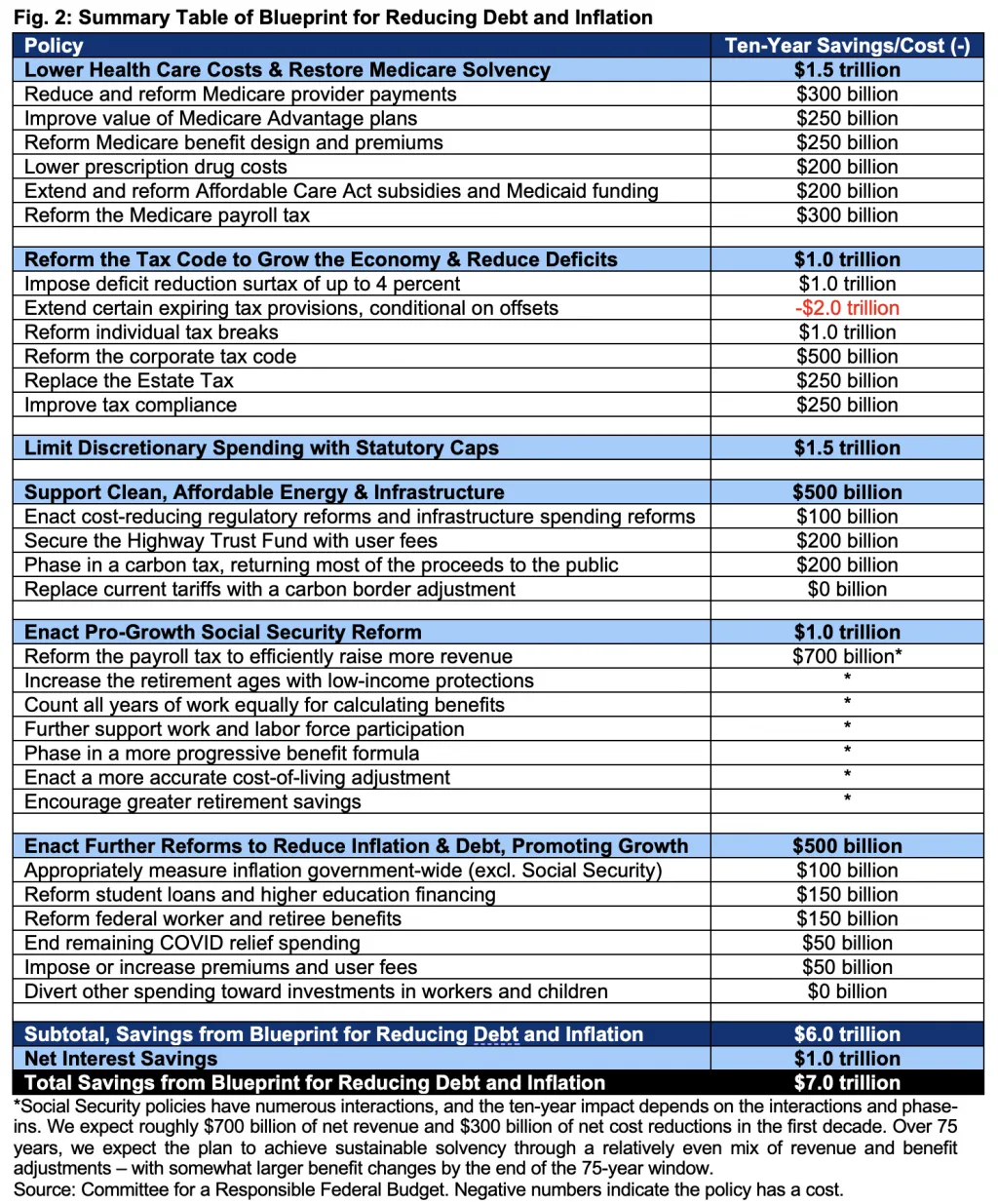

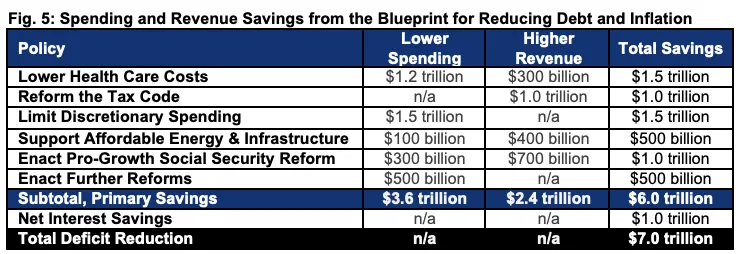

This blueprint puts forward a framework to achieve these goals through a combination of revenue and spending changes – with savings from health care, tax reform, discretionary spending caps, energy reforms, Social Security solvency, and other changes to the budget. About 40 percent of the deficit reduction comes from revenue and 60 percent from changes in spending.

Summary of Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation

Confronting Our Fiscal and Economic Challenges

The United States faces several overlapping fiscal and economic challenges. Most immediately, the U.S. is experiencing its highest inflation rate in over four decades. Meanwhile, the national debt is approaching record levels and growing at an unsustainable pace, with interest costs representing an increasingly large share of the budget. Additionally, the country faces slowing economic growth as the population ages and labor productivity growth remains low as well as growing income inequality, emerging technologies, and a series of geopolitical threats.

Inflation is rising well in excess of the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target, with the Consumer Price Index up 8.2 percent over the past year and the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index up 6.2 percent. Meanwhile, economic growth is stagnating; forecasters expect almost no growth this year and less than 2 percent annual growth for the foreseeable future.

At the same time, we project the national debt will grow unsustainably, from less than 98 percent of GDP at the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 to a record 116 percent by 2032 – exceeding the previous high of 106 percent of GDP set just after World War II. Annual deficits by the end of the decade will reach 6.6 percent of GDP. Interest costs are also rising rapidly and are on course to reach a record 3.4 percent of GDP by 2032.

Excessive borrowing has contributed to these challenges by exacerbating inflation, adding to the debt, and crowding out productive investments. The Federal Reserve’s efforts to reduce inflation through higher interest rates could worsen other challenges by driving up federal interest costs, discouraging business investment, and increasing the chances of a recession.

Deficit reduction can assist the Federal Reserve in its effort to fight inflation, reducing the magnitude of rate hikes needed and thus the chances of recession. Thoughtful deficit reduction can also promote a stronger labor force, greater investment, and more economic growth. And importantly, it can put the national debt on a more sustainable long-term path.

Principles of Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation

A comprehensive plan to put the budget on a sustainable path should seek to accomplish several goals. Apart from the most important principle of responsible budgeting – making the necessary tradeoffs to balance governing priorities – this blueprint considers five other key principles:

- Stabilize and reduce the debt as a share of the economy. With debt on track to exceed its World War II record as a share of the economy in just six years, any budget plan should primarily focus on putting the debt on a more sustainable path. Failing to do so means leaving us at increased risk of higher interest rates and slower growth, vulnerable to increased pressures from foreign governments and financial markets, and with fewer tools to address future needs and crises. A comprehensive plan should prevent debt from rising as a share of the economy and, in the longer run, shrink debt to a more manageable share of GDP.

- Support the Federal Reserve’s efforts to fight inflation. While the Federal Reserve is appropriately charged with fighting inflation, Congress and the President should help steer inflation in the right direction given the current challenge. Using fiscal policy to help fight inflation ensures all policy is moving in the same direction, spreads the impact of inflation reduction across the economy, and reduces the likelihood and/or severity of recession. A thoughtful budget plan should work to temper demand, boost supply, and lower prices.

- Secure the major trust funds to prevent insolvency. Three federal trust funds, financing Social Security, Medicare Hospital Insurance, and highway funding, are on track to be insolvent within the next 12 years. Upon insolvency, the law calls for abrupt cuts in benefits or spending. Current budget conventions assume lawmakers will borrow to continue these programs, which is one major reason for the nation’s unsustainable long-term budget outlook. A budget plan should restore long-term solvency to these trust funds to improve the fiscal outlook and so that current workers and retirees know they can count on these vital programs.

- Promote long-term economic and income growth. A budget plan should support economic competitiveness by ensuring the federal budget and tax code are conducive to long-term economic and income growth. Lower debt can help to grow the economy, and specific policy reforms can further support work, promote investment, and reduce distortions. A stronger economy means higher incomes, better standards of living, and more sustainable debt.

- Support fairness and efficiency throughout the tax code and budget. A budget plan should not only reduce the gap between spending and revenue, but also improve the way we tax and spend. Currently, the federal government spends $6 on the elderly for every $1 for children. Meanwhile, a number of spending programs and tax breaks subsidize those who need help the least and spend far more than necessary to accomplish their stated goals. A budget plan should consider how to structure the budget and tax code more efficiently to better target resources where they are needed and can do the most good.

How the Blueprint Will Fight Inflation

In Fiscal Policy in a Time of High Inflation, we explain the macro-economic case for using fiscal policy to assist the Federal Reserve in fighting very high levels of inflation. In addition to stabilizing debt as a share of the economy and promoting long-term economic growth, the Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation is designed to help reduce near-term inflation rates, lower inflation expectations, and allow the Federal Reserve to ease up on interest rate hikes.

Although we have not yet undertaken a full analysis of the plan, a preliminary assessment suggests it could plausibly reduce near-term inflationary pressures by about 1 percentage point while substantially reducing the risk of persistent inflation.* This lower inflationary pressure will lead prices to rise more slowly than otherwise expected while allowing the Federal Reserve to end rate hikes sooner and reduce interest rates back to their long-term neutral level more quickly.

As Fiscal Policy in a Time of High Inflation explains, fiscal policy can fight inflation by tempering demand, boosting supply, and lowering prices. The blueprint is crafted to do all three:

- Temper Demand: The blueprint would reduce demand for consumption of goods and services in the economy, chiefly by reducing transfers to and increasing revenue collection from higher-income households. In total, we estimate the blueprint would reduce non-interest deficits by roughly $350 billion in the first calendar year and more than $1.3 trillion over three years. The blueprint would further reduce demand by increasing the incentive for households to save more for retirement through income tax and Social Security reforms.

- Boost Supply: The blueprint would boost the supply of labor and capital in the economy by supporting and encouraging work and investment. The blueprint would promote work by expanding the earned income tax credit, enacting a number of Social Security reforms to reward delayed retirement, reforming work requirement rules, investing in programs like preschool that help parents return to work, and supporting disabled workers. The blueprint would increase investment by lowering deficits and debt, reforming costly regulations, extending expensing of research and equipment, and scheduling a future price on carbon.

- Lower Price: The blueprint would directly lower several prices either set or heavily influenced by the federal government. In particular, it would reduce the price of a variety of health care services, prescription drugs, and health insurance. It would also reduce the price of public and private infrastructure and shipping through several regulatory reforms such as repeal of the Jones Act. The blueprint would further drive down prices throughout the economy by reducing numerous cost-boosting subsidies throughout the tax code and budget and by reducing tariffs in a revenue-neutral manner.

By reducing inflationary pressures now and in the future, the blueprint would also lower the risk of a recession and lower the budgetary cost of Federal Reserve efforts to cut inflation.

*This analysis focuses on the impact of the blueprint on nominal Personal Consumption Expenditures over calendar year 2023 – assuming most parts of the plan are implemented at the beginning of 2023 and the Federal Reserve does not adjust to changes in the economy. In reality, we expect lower inflationary pressure to lead to a combination of lower inflation and less Fed tightening. We assume roughly 90 percent of new spending would flow through to prices.

Selecting a Fiscal Goal

Any comprehensive budget plan should focus on achieving fiscal sustainability. Understanding that there is no one right way to measure that sustainability, it is nonetheless helpful to set a specific fiscal goal and then put forward tax and spending plans to meet that goal.

Selecting a fiscal goal requires deciding the metric to focus on (for example, deficits or debt), the specific target to aim for (for example, debt at 100 percent of GDP or primary budget balance), and the time frame for achieving that goal (for example, five, ten, or 20 years).

The below table shows the savings needed – over the relevant time periods – to achieve a variety of debt-to-GDP and deficit targets. Estimates are based on our updated budget baseline projections. For example, stabilizing debt at its current level of 97.5 percent of GDP would require $1.5 trillion of savings over five years, $6.9 trillion over ten years, and $25.8 trillion over 20 years. Savings for deficit-based targets vary based on the path, but assuming the path in our blueprint, we estimate it would require $14.6 trillion to balance the budget in ten years.

The blueprint would save $7 trillion over a decade, enough to stabilize debt as a share of the economy and reduce deficits to below 3.5 percent of GDP. Incorporating the economic effects of the plan on inflation, interest rates, and growth, we estimate it would reduce debt to 94 percent of GDP and deficits to 2.9 percent of GDP. We are also hopeful that strong revenue collection over the past year will continue, improving the current law fiscal outlook.

Even under these more optimistic scenarios, however, the national debt will remain extremely high by historic standards. While all incremental improvements to the budget outlook are welcomed – and enacting even a $1 trillion deficit reduction plan would be an important step in the right direction – our plan should be viewed as the minimum of what is ultimately needed.

Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation

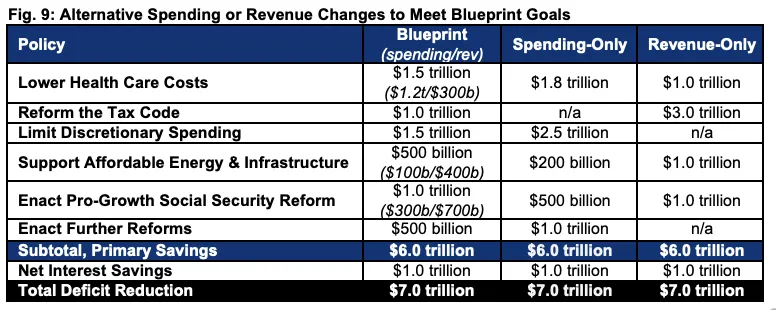

The Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation represents one illustrative framework to improve the federal budget outlook along with discussion of the types of policy changes that could fit within the framework. There are many other ways to improve the federal budget – Appendix I discusses two alternatives that generate similar savings entirely with spending or entirely with revenue.

The blueprint includes savings from all major areas of the budget and tax code, with a focus on reducing inflationary pressures, securing trust funds, promoting economic and income growth, improving fairness and efficiency, and putting the national debt on a more sustainable path.

The plan would reduce the debt by $7 trillion over the next decade. It includes roughly $1.5 trillion of health care savings, $1.0 trillion of income tax revenue, $1.5 trillion of discretionary savings, $500 billion of energy and infrastructure savings, $1 trillion from Social Security solvency measures, $500 billion of savings from other reforms, and $1 trillion of interest savings. Most of these areas include proposals to lower projected spending and to increase revenue collection.

Relative to our baseline, three-fifths of the primary deficit reduction in the plan comes from lower spending and two-fifths from higher revenue. If measured relative to a current policy baseline that assumed the extension of tax cuts and faster discretionary growth, that ratio would be roughly fifty-fifty. Similarly, slightly more than half of the savings come from either revenue or lower defense spending and the rest from lower domestic spending.

Importantly, the blueprint puts forward example areas of savings along with rough estimates of how much can be generated in each area. Although we use specific policy choices to generate these savings estimates, the blueprint does not endorse specific policy details. Most of the savings discussed in this plan could be generated in a variety of ways. At the same time, we welcome policymakers, thought leaders, and engaged citizens to put forward alternative proposals.

While individuals may disagree with the specific composition of this plan, it is meant to serve as a discussion draft and the beginning of a larger conversation on what it will take to put the national debt on a downward sustainable path.

Lower Health Care Costs and Restore Medicare Solvency ($1.5 Trillion)

The high and rising cost of health care represents the single largest threat to the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook and the single greatest opportunity to help control inflation. With the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund projected to be insolvent in 2030, according to the Congressional Budget Office, and health costs continuing to grow, thoughtful reforms can not only lower prices in the economy, but also improve the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook.

We suggest roughly $1.5 trillion of federal health savings and related revenue increases, which will also lead to lower beneficiary premiums and out-of-pocket costs. Specifically, we suggest:

- Reduce and reform Medicare provider payments ($300 billion), for example by enacting MedPAC recommendations to immediately reduce certain excessive post-acute care payments, equalizing Medicare payments regardless of site-of-care, restructuring graduate medical education funding, eliminating bad debts reimbursements, expanding bundled payments, and replacing the Medicare sequester with a one-time rebasing of payment rates.

- Improve value of Medicare Advantage plans ($250 billion), for example by enacting appropriate coding intensity adjustments to reduce excessive payments, improving the quality bonus program, and/or introducing competitive bidding between plans.

- Reform Medicare benefit design and premiums ($250 billion), for example by reforming Medicare’s benefit design to combine an out-of-pocket cap with more first-dollar cost sharing, restricting the use of supplemental plans, increasing premiums for higher earners, and removing the cap on Part D premiums so they continue to cover one-quarter of costs.

- Lower prescription drug costs ($200 billion), for example by strengthening the price negotiations and inflation cap from the Inflation Reduction Act and applying them to plans in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health care exchanges, supporting the introduction and use of more generic drugs, and reforming how we reimburse physicians in Medicare Part B to encourage the use of lower-cost drugs.

- Extend and reform ACA subsidies and Medicaid funding ($200 billion), for example by limiting the ability of states to use provider taxes or intergovernmental transfers to inflate the reported cost of their Medicaid programs, adopting a more progressive version of the recent ACA subsidy changes, recapturing subsidy overpayments, restoring cost-sharing reduction appropriations, strengthening enforcement of the employer mandate, limiting provider payment rates in the exchanges, and/or adjusting Medicaid matching rules. Savings could be used in part to extend enhanced ACA subsidies scheduled to expire after 2025 and/or to expand coverage to those in the Medicaid coverage gap.

- Reform the Medicare payroll tax ($300 billion), for example by replacing the 1.45 percent employer tax with a more efficient compensation tax and broadening the self-employment payroll tax to cover certain business income not already taxed by the net investment income tax.

Reform the Tax Code to Grow the Economy and Reduce Deficits ($1 Trillion)

Any realistic solution to our nation’s fiscal challenges will require raising additional revenue and making improvements to the fairness and efficiency of our tax code while promoting growth and reducing inflationary pressures. It must also address current law expirations of huge parts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that fuel uncertainty and would be costly to extend.

We propose a two-part tax plan, including a comprehensive, revenue-neutral tax reform that addresses and pays for various expirations, as well as a $1 trillion deficit reduction surtax on individuals and corporations. Specifically, we suggest to:

- Enact a Broad Deficit Reduction Surtax ($1 trillion) on individual and corporate income – with few deductions and exclusions – which would stay in effect so long as the budget is out of balance but phase down with very low deficits. Parameters should be decided based on revenue estimates, but the surtax could, for example, impose a 1 percent tax on income above $50,000 ($100,000 for couples), a 2 percent tax on income above $250,000 ($500,000 for couples), and a 4 percent tax on corporate income and individual income above $2.5 million ($5 million for couples). This would increase the top effective ordinary income tax rate to 41 percent (39 percent in most cases), increase the top effective capital gains tax rate to 27.8 percent, and raise the top effective corporate income tax rate to 25 percent.

- Extend Certain Expiring Tax Provisions, Conditional on Offsets (-$2 trillion), such as expansions of the standard deduction and child tax credit (CTC) in place of the personal exemption, caps to the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and other deductions, expensing of equipment and research & experimentation, cuts to personal tax rates, and some further expansions of the CTC and earned income tax credit that were in place temporarily in 2021. Some provisions, such as tax breaks for pass-through income and opportunity zones, could be allowed to expire. Total extensions should be limited to the size of available offsets, as described below.

- Reform Individual Tax Breaks ($1 trillion), for example by fully repealing the SALT deduction, better targeting other deductions, improving and tightening various rules around asset sales and transfers, reforming the tax treatment of partnerships, and cutting other tax breaks. Some revenue could be used to reform and expand provisions supporting work, retirement savings, and childrearing.

- Reform the Corporate Tax Code ($500 billion) by improving international tax rules for multinational corporations, repealing the corporate SALT deduction, strengthening limits on interest deductibility, and modifying or repealing various corporate tax breaks.

- Replace the Estate Tax ($250 billion) with a new inheritance tax for large bequests and new rules requiring the basis of assets passed on after death to be carried over for capital gains purposes.

- Improve Tax Compliance ($250 billion), for example by expanding information reporting, giving the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) new authorities/flexibilities along with increased accountability, closing loopholes that encourage tax evasion and avoidance, and ensuring adequate IRS funding.

Limit Discretionary Spending ($1.5 Trillion)

In the 1990s, and again between 2012 and 2021, policymakers relied on statutory defense and nondefense discretionary spending caps to limit how much appropriators could spend each year. While caps are only as strong as the willingness of politicians to abide by them, they can still make a meaningful difference in keeping discretionary spending under control.

However, lawmakers began to increase these caps significantly in 2018 and were completely unconstrained by caps last year. As a result, ordinary discretionary appropriations levels have grown by 29 percent since 2017 and may increase more this year. Further increases will exacerbate inflationary spirals and worsen the nation’s fiscal outlook.

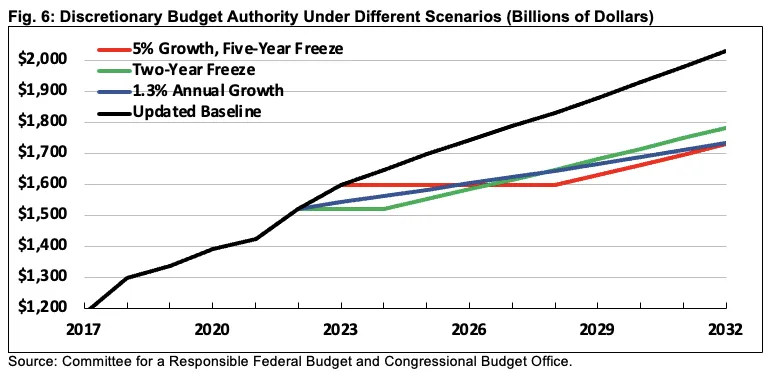

We recommend restoring discretionary spending caps and setting achievable annual targets for appropriations, with the goal of reducing spending by roughly $1.5 trillion below baseline over the next decade.

The $1.5 trillion of savings could be achieved by limiting this year’s increase to 5 percent and then freezing regular appropriations for the subsequent five years, instituting a two-year freeze, or growing discretionary spending by 1.3 percent per year for the next decade.

To ensure discretionary caps effectively limit spending, we suggest strengthening enforcement of the caps and limiting workarounds. For example, appropriators should not be allowed to use phony changes in mandatory programs (CHIMPs) to offset real increases in discretionary spending; emergency designations should be limited to the current administrative definition of an emergency and require two-thirds majority support; and new discretionary commitments in excess of the caps should require offsets from the budget or tax code.

Support Clean and Affordable Energy and Infrastructure ($500 billion)

Any comprehensive plan to fight inflation and improve our nation’s fiscal and economic outlook should include policies to support affordable energy and infrastructure. The high cost of fossil fuel has been a key driver of recent inflation. Costly and unpaid-for infrastructure projects are slated to increase medium-term deficits, while the effects of carbon emissions on global climate change are projected – among other consequences – to slow long-term economic growth.

At the same time, the Highway Trust Fund faces a $150 to $220 billion funding gap over the next decade as gas tax revenue has stagnated. Meanwhile, new efforts to bolster clean energy production – supported by spending and tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act – are being stifled by antiquated rules and bureaucratic red tape that continues to drive up costs.

We propose roughly $500 billion of deficit reduction from energy and infrastructure-related policies, including revenue, spending, and regulatory changes. Specifically, we suggest to:

- Enact cost-reducing regulatory reforms and reform infrastructure spending ($100 billion), including by enacting comprehensive permitting reforms, accelerating leasing of federal lands, and repealing or modifying laws that drive up the cost of energy and infrastructure such as the Jones Act, Foreign Dredge Act, Davis-Bacon Act, and Buy American Act. Appropriations should be adjusted to account for lower spending, and further cost reductions could come from requiring larger state contributions for certain projects and ensuring temporary spending from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is allowed to expire after 2026 as intended.

- Secure the Highway Trust Fund with user fees ($200 billion), for example by imposing a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fee on commercial vehicles so they pay for their use of roads, allowing more tolling on state highways, and/or through other reforms.

- Phase in a carbon tax, returning most of the proceeds to the public ($200 billion) by putting a price on carbon (see our Build Your Own Carbon Tax tool for possible parameters) and using most of the revenue for assistance, fixed-dollar energy rebates, tax reductions, new investments, or some combination. The carbon tax and distribution could be phased in gradually to avoid boosting inflation. Once fully in effect, the carbon tax could continue to grow while distributions of the new revenue remain flat, with additional funds going toward deficit reduction.

- Replace some current tariffs with a carbon border adjustment ($0) in order to reduce the price of traded goods in the near term while effectively applying the U.S. carbon tax to imported goods as it is phased in.

Enact Pro-Growth Social Security Reform ($1 trillion)

The Social Security trust funds are less than 13 years from insolvency. Thoughtful comprehensive Social Security reforms would not only secure benefit payments, but also improve the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook and promote long-term economic growth. Reforms can also help to reduce inflationary pressures, if enacted promptly, by supporting higher labor force participation for those who want to work, encouraging higher rates of savings (thus tempering demand), and by reducing the growth of spending and tax breaks that may lead to persistent inflation.

We propose enacting a 75-year solvency plan similar to the framework put forward by Goldwein, MacGuineas, and Towner in Promoting Economic Growth through Social Security Reform, with a greater emphasis on combating inflation and reforming the payroll tax. We suggest a relatively even mix of revenue increases and benefit adjustments over time, with revenue more frontloaded and benefit changes more backloaded. Specifically, we suggest to:

- Reform the payroll tax to efficiently raise more revenue, for example by replacing the employer-side tax on wages up to $160,200 with a compensation tax that covers all wages above the cap as well as health, stock option, and other fringe benefits. The compensation tax could have a lower tax rate than the payroll tax and could be phased in.

- Increase the retirement ages, with low-income protections, for example by raising the normal retirement age to 68 and then indexing it to longevity growth while creating a new age 62 poverty protection benefit and adjusting other ages.

- Count all years of work equally for calculating benefits, including by eliminating the ten-year minimum and 35-year maximum for years counted and adopting the “mini-PIA,” which applies the Social Security benefit formula to each year of work rather than average lifetime wages.

- Further support work and labor force participation, for example by repealing the antiquated retirement earnings test, better explaining the financial benefits of delayed retirement, and enacting a suite of reforms to better support disabled workers.

- Phase in a more progressive benefit formula that boosts benefits for low-income beneficiaries while slowing benefit growth for higher-income beneficiaries.

- Enact a better cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) that does less to perpetuate high inflation by calculating COLAs with the more accurate chained Consumer Price Index (chained CPI) and capping COLAs for very high earners, for example as a percentage of the median or maximum benefit.

- Encourage greater retirement savings, for example by establishing automatic retirement account contributions on top of Social Security with an option to opt out or strengthening automatic retirement savings enrollment outside of Social Security.

Enact Further Reforms to Reduce Inflation, Promote Growth, and Lower Debt ($500 billion)

Policymakers should reduce wasteful spending and improve program efficiency and efficacy throughout the federal budget. We suggest a focus on policies that can help reduce inflationary pressures, boost economic capacity, strengthen program integrity, and ensure companies and individuals are appropriately paying for government-provided services.

We suggest roughly $500 billion of net savings, which could include targeted investments, focused on strengthening the supply side of the economy. Savings could come from policies to:

- Appropriately measure inflation government-wide ($100 billion) by calculating inflation-indexed parameters in the budget using the chained CPI rather than the traditional CPI (which economists agree overstates the rate of inflation).

- Reform student loans and higher education financing ($150 billion), including by replacing President Biden’s proposed Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) changes with a new consolidated IDR program that better supports low-income undergraduate borrowers while avoiding windfall benefits to those with graduate degrees, and adopting a series of additional reforms to streamline subsidies, prevent excessive borrowing, and improve college accountability.

- Reform federal worker and retiree benefits ($150 billion), for example by adjusting the formula for calculating civilian and military pensions, increasing worker pension contributions, adopting a premium-support model to limit the cost of federal worker and retiree health benefits, modifying rules related to the TRICARE premium, or limiting double-dipping of certain veteran and military benefits concurrently or general federal benefits.

- End remaining COVID relief spending ($50 billion), including by ending the public health emergency and related spending in January 2023, rescinding unused relief funds other than those directly related to the COVID-19 virus and disease, and supporting efforts to recover pandemic relief fraud and overpayments. A portion of savings could be reinvested in COVID prevention and treatment as well as preparation for future pandemics.

- Impose or increase premiums and user fees ($50 billion), for example by extending airport security fees and customs fees, increasing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guarantee fees, charging private jets for use of air traffic control, and imposing new user fees for food safety inspection.

- Divert other spending toward investments in workers and children ($0), for example by investing more in preschool, child care, and/or job placement and training, paid for by strengthening government-wide anti-fraud efforts, using government data to better enforce eligibility rules, reforming work requirements, cutting farm subsidies that encourage food inflation, better aligning program eligibility rules to match intent, and cutting certain overlapping payment.

Net Interest Savings ($1 trillion)

By reducing the federal debt burden, we estimate the above blueprint would generate roughly $1 trillion of net interest savings for the federal government – though that number could be higher or lower depending on policy details and phase-ins.

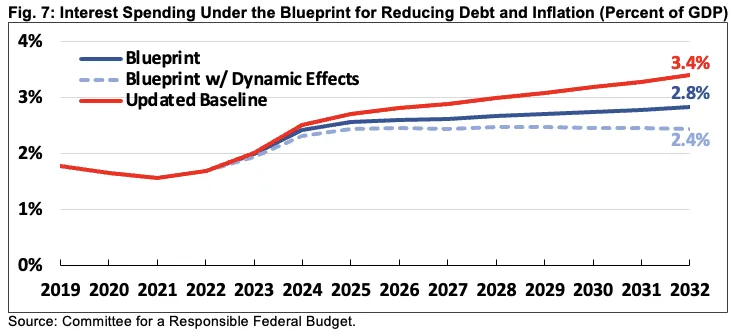

Reductions in debt service will grow over time, helping to slow the increase in net interest payments expected under current law. By 2032, we estimate the blueprint would reduce federal interest payments by about $200 billion per year. And instead of growing to a record 3.4 percent of GDP by that year as under our baseline, it would only grow to 2.8 percent of GDP.

If this blueprint were successful in holding down interest rates and promoting faster economic growth, interest costs would grow even more slowly. Although we have not run a full dynamic estimate of the plan, a rough preliminary analysis suggests it could hold interest costs to 2.4 percent of GDP by 2032.

The Economic and Fiscal Impact of the Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation

The Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation will lower deficits and debt; help to fight inflation; restore long-term solvency to Social Security, Medicare, and the Highway Trust Fund; strengthen economic and income growth; and improve fairness and efficiency within the government.

Although the exact fiscal impact of the plan will depend on parameter details, we estimate it will be sufficient to stabilize debt as a share of the economy over the next decade and reduce it over the long term.

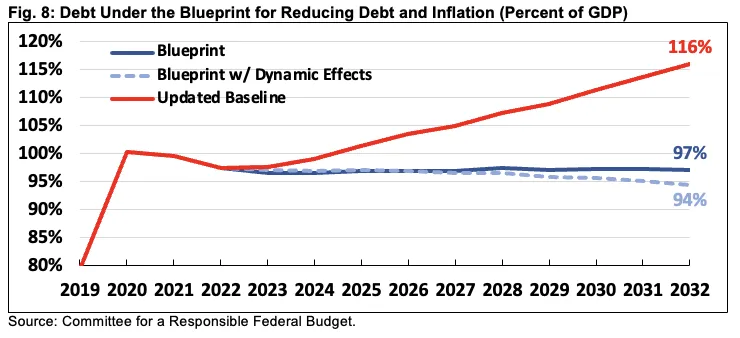

Under current law, we estimate debt will reach 116 percent of GDP by 2032. Under the blueprint, debt would remain stable below 98 percent of GDP throughout the decade, falling to 97 percent of GDP by 2032 and continuing to decline thereafter. Assuming the blueprint leads to modestly stronger economic growth, lower inflation, and lower interest rates, we estimate debt would fall further to 94 percent of GDP by 2032.

In addition to reducing projected debt from 116 percent of GDP to 97 (or 94) percent in 2032, we estimate it would reduce deficits from 6.6 percent of GDP to 3.4 (or 2.9) percent and interest payments from a record 3.4 percent of GDP to 2.8 (or 2.4) percent.

The blueprint would also help to lower inflationary pressures and support stronger economic growth. Our preliminary findings suggest the blueprint could plausibly reduce inflationary pressures by as much as 1 percentage point in the near term. By 2032, we find it could plausibly reduce interest rates by 50 basis points and boost GDP by 1 percent. Over the long run, we expect the blueprint would substantially boost the rate of economic growth over current projections.

The blueprint will restore 75-year solvency to Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance, put the national debt on a clear downward path over the next 30 years, and increase progressivity and generational equity in the budget and tax code.

Conclusion

The Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation proposes $7 trillion of deficit reduction, including spending and revenue adjustments that come from lowering health care spending, boosting income tax revenue, reforming energy and infrastructure policy, capping discretionary spending, restoring solvency to Social Security and other trust funds, and reforming other parts of the budget.

The blueprint would help the Federal Reserve to control inflation, prevent insolvency of the major trust funds, improve fairness and efficiency throughout government, promote stronger economic growth, and stabilize the debt as a share of the economy.

Incorporating economic impacts, the blueprint would put the national debt on a downward path as a share of the economy – particularly over the long term.

There is no one right way to address our nation’s unsustainable fiscal situation, but inaction is not a reasonable option. The blueprint puts forward a general framework for deficit reduction but allows substantial flexibility over the precise details. We encourage those who disagree with this framework to put forward their own budget plans to at least make progress toward addressing the nation’s massive deficits and rising debt.

With inflation surging, interest rates rising, and debt approaching record levels, now is the time for serious solutions to our unsustainable fiscal situation.

Appendix I: All-Spending and All-Revenue Alternatives

This blueprint puts forward one possible way to put the federal budget on a more sustainable path. However, many other alternatives exist.

The blueprint reduces primary spending by $3.6 trillion, or 5.5 percent, below projections over the next decade. It increases revenue by $2.4 trillion, or 4.3 percent, above projections. The same amount of savings could be generated by instead reducing primary spending by 9.1 percent or increasing revenue by 10.7 percent.

An all-spending plan could remove the $2.4 trillion of revenue increases from the blueprint and replace it with additional savings in health care, discretionary spending, and other parts of the budget. For example, it could freeze discretionary spending for a full decade, raise Medicare premiums across the board, reduce the Medicaid matching rate, shrink federal highway spending, enact more aggressive Social Security benefit changes, and enact additional spending cuts, including to safety net programs.

An all-revenue plan could replace $3.6 trillion of spending reductions with further income tax, carbon tax, and payroll tax revenue. For example, this plan could place aggressive limits on the tax exclusion for employer-provided health care, allow tax rate cuts and expensing provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to expire as scheduled, dedicate a much larger share of the carbon tax toward deficit reduction, and further increase revenue for Social Security.

Although these alternative plans would plausibly save enough money to stabilize debt, they require much more aggressive changes to the budget or tax code. Indeed, the more parts of the budget or tax code that are taken off the table, the more aggressive changes will have to be.

For example, saving $7 trillion from reducing spending other than Social Security. Medicare, and defense would require a 22 percent cut to other spending. Generating those funds from taxing high earners would be close to impossible – it would require raising the top tax rate to its revenue-maximizing level (about 70 percent), eliminating virtually all tax preferences for high earners, and implementing an aggressive wealth tax.

Appendix II: Baseline and Estimates

The Baseline

In order to develop this blueprint, we first had to construct a baseline to measure it against. While standard practice is to rely on the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) current law baseline, the latest CBO baseline is out of date. Specifically, the CBO baseline is based on economic data from March 2022 and legislative and executive actions as of April 2022. A significant number of economic and policy changes have taken effect since that time.

In order to begin from the most accurate starting point possible, we adjusted the CBO baseline in the following ways:

- Incorporating all legislation enacted since the previous baseline, based on CBO scores and estimates of each bill.

- Incorporating all executive actions put forward since the previous baseline, using a combination of CBO, OMB, and our own estimates. For rules and actions that have not yet been finalized, we used the “50% rule” and assume half their costs.

- Incorporating changes to actual and expected economic variables – including real GDP, inflation rates, and interest rates – based on actual data, median forecasts from the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC), and our own estimates. We use CBO’s “Workbook for How Changes in Economic Conditions Might Affect the Federal Budget” to integrate these into the baseline.

- Changing GDP estimates to incorporate Bureau of Economic Analysis revisions.

- Adjusting borrowing in fiscal year 2022 and future years, based on final 2022 fiscal data.

- Removing extrapolated costs of certain one-time spending related to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The effects of these changes move in different directions but overall lead to higher debt-to-GDP. Specifically, we estimate debt in 2032 will be $42.9 trillion and 116 percent of GDP, compared to CBO’s previous projection of $40.2 trillion and 110 percent of GDP. We estimate deficits in 2032 will be $2.4 trillion (6.6 percent of GDP), compared to CBO’s $2.3 trillion (6.1 percent of GDP).

Estimating Sources of Methods

The blueprint proposes areas of budgetary savings along with examples of policies that could meet savings targets in each area. Numbers in this report are rough and rounded but built from scores and estimates of actual policy proposals.

In most cases, the policy savings underlying the targets come from CBO or the Joint Committee on Taxation. In some cases, estimates come from other credible sources – including our Health Savers Initiative – or Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget staff. Estimates are generally adjusted to reflect new budget windows and changes in economic and legislative condition. For purposes of this plan, we assume most policies are implemented in 2023 – though this assumption will become increasingly unrealistic as more time passes.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image