New Paper Estimates Upper Limit on Debt

In a new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists Vadim Elenev, Tim Landvoigt, and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh proposed a new indicator of fiscal capacity they call the “austerity threshold.” This new indicator is the theoretical level of debt as a share Gross Domestic Product (GDP) beyond which delaying adjustment would make a debt spiral unavoidable – even with maximum austerity measures – at which point government debt would no longer be “risk-free.” The authors calibrated their model to the United States and found that:

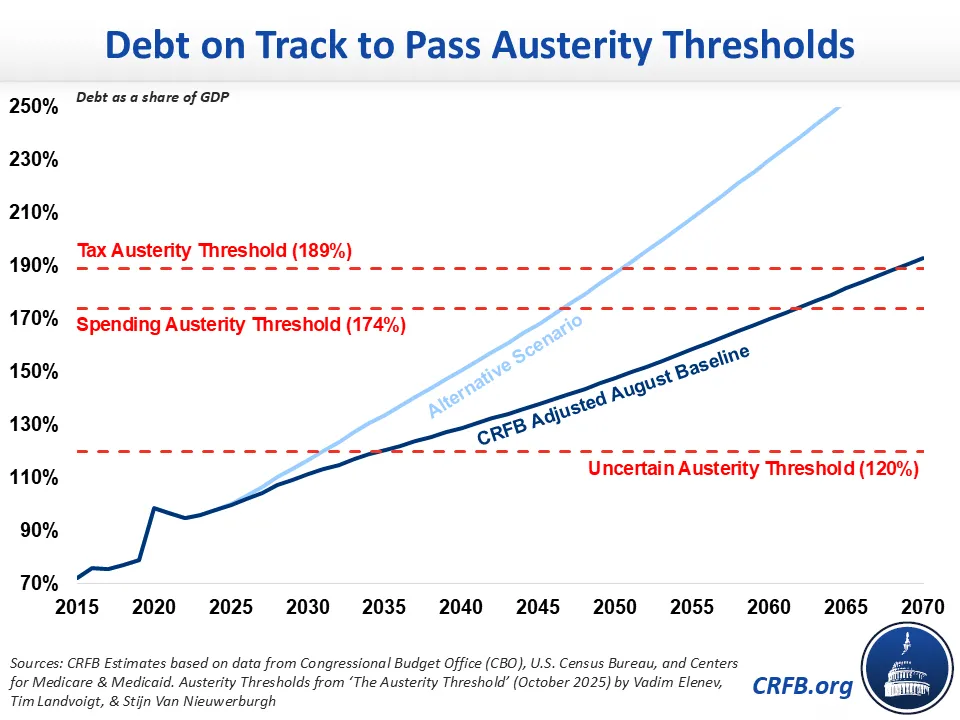

- If the U.S. committed to austerity through tax increases alone, debt could reach 189% of GDP before austerity would be required to prevent risking a debt spiral; under the CRFB Adjusted August 2025 Baseline, this level is hit in fiscal year (FY) 2069 or FY 2051 under our alternative scenario.

- If the U.S. committed to austerity through spending cuts alone, debt could reach 174% of GDP before austerity would be required; debt will reach that level in FY 2062 under the CRFB Adjusted August 2025 Baseline or FY 2047 under the alternative scenario.

- If it’s uncertain whether austerity will be implemented through tax increases or spending cuts, the threshold plummets to just 120% of GDP; under the CRFB Adjusted August 2025 baseline, debt reaches that level in FY 2035 or FY 2031 in the alternative scenario.

To estimate these austerity thresholds for the U.S., the authors constructed a macroeconomic model where “the government is committed to keeping debt risk-free but delays any fiscal adjustment until absolutely necessary.” They modeled scenarios where the government commits to raise taxes to generate surpluses when necessary, where it cuts spending to achieve the same, and where the policy is uncertain and can change through the election cycle. In all their scenarios, the government is fully committed to implement austerity when it hits the threshold.

The authors found that committing to austerity through tax increases would give the government the most fiscal capacity, and debt could reach 189% of GDP before the tax increases need to take effect. However, the government’s ability to raise tax revenue is ultimately limited by the Laffer curve, which shows that tax rates can only be raised to a limited revenue-maximizing level before higher rates will result in less revenue collection due to significantly fewer hours worked. If debt surpasses 189% of GDP, economic shocks could cause a debt spiral even if the government maximizes tax revenue. Under our Adjusted August 2025 Baseline, debt will reach 189% of GDP in FY 2069 under current law. Under an alternative scenario, where certain tariff provisions are ruled illegal, the temporary provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) are made permanent without offsets, and interest rates remain above the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) January 2025 projections, debt would reach that threshold in FY 2051.

If the government committed to austerity through spending cuts, the debt threshold would be reduced to 174% of GDP. The authors assume that spending cannot be cut below zero and must be at least 0.1% of GDP to keep the economy functioning. Under our baseline estimates, debt will reach 174% of GDP in FY 2062 under current law and in FY 2047 under our alternative scenario.

These two scenarios assume the government fully commits to either austerity through tax increases or spending cuts and that the policy does not change. However, the authors also considered scenarios where the policy could change randomly throughout the presidential cycle. When there was a 50% chance of either policy, they found that the threshold drops dramatically to just 120% of GDP1; under our baseline estimates, debt will reach that level in FY 2035 under current law and as soon as FY 2031 in our alternative scenario.

The austerity threshold is a useful framework to quantify fiscal capacity and model how it is impacted by policy choices, and it has some important lessons for policymakers. The large differential between the spending and revenue scenarios and the uncertain scenario shows how policymakers would benefit from putting in place a plan to get debt under control sooner rather than later.

However, it’s important to understand that these thresholds are theoretical upper limits on how much debt the government can issue without risking a debt spiral. They are not thresholds where debt begins to have negative consequences. The authors point out that increased government borrowing crowds out private investment and labor supply before the austerity threshold is reached, reducing economic growth and lowering national income per person. Furthermore, putting off fiscal adjustments until absolutely necessary forces the government to implement the austerity policy no matter what, even if there’s a recession or crisis, and even if extreme tax increases or spending cuts are required to reach a surplus.

This paper reiterates the need for policymakers to take seriously our precarious fiscal situation and spells out some potential consequences of failing to do so. Policymakers should act quickly to put in place a plan that puts the national debt as a share of GDP on a downward sustainable trajectory.

1 The authors note in their paper: “In an economy where austerity consists of spending cuts with 50% probability and of tax hikes with 50% probability, fiscal capacity shrinks to just 120% of GDP. The reason is the near-opposite effects of the two austerity policies on bond yields and debt valuation. A switch from tax hikes to spending cuts in the austerity region can trigger a sudden increase in the market value of government debt. If the debt level at which this switch occurs is already high, the jump pushes the ratio beyond the level that spending cuts can stabilize. Ruling out explosive debt dynamics requires a much lower austerity threshold. Conversely, the possibility of switching from spending cuts to tax hikes (and the resulting sudden devaluation of government bonds) generates high ex-ante bond risk premia, raising borrowing costs and making austerity more likely. If some political parties prefer tax increases and other spending cuts, uncertainty about austerity regimes could reflect uncertain future political power transitions.”