The Nation's Upcoming Fiscal Challenges

President Joe Biden and the nation face perhaps the most daunting fiscal situation on record. One hundred days into his presidency, President Biden faces record deficits and debt, expiring discretionary spending caps, a series of looming fiscal deadlines, several major trust funds facing shortfalls, and no agreement on how to address these challenges. As the economy recovers and the President pushes for an agenda that calls for higher spending and taxes, the country is confronted with:

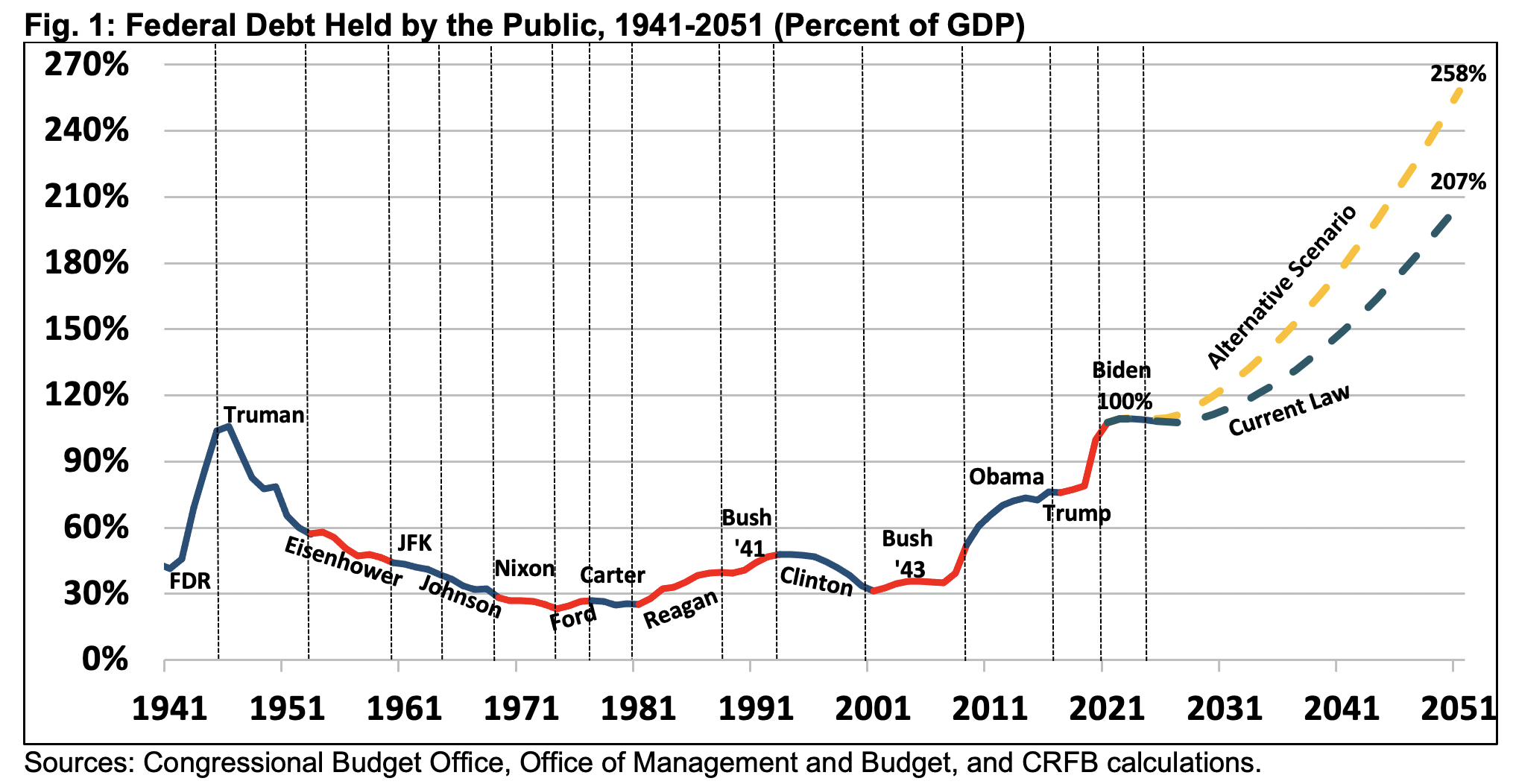

- Record Debt Levels: Debt held by the public will total 108 percent of Gross Domestic Product this fiscal year. After the previous record of 106 percent of GDP, set in 1946 just after World War II, policymakers ran years of balanced budgets to bring debt down to manageable levels. We now face large structural deficits and an ever-rising debt-to-GDP ratio.

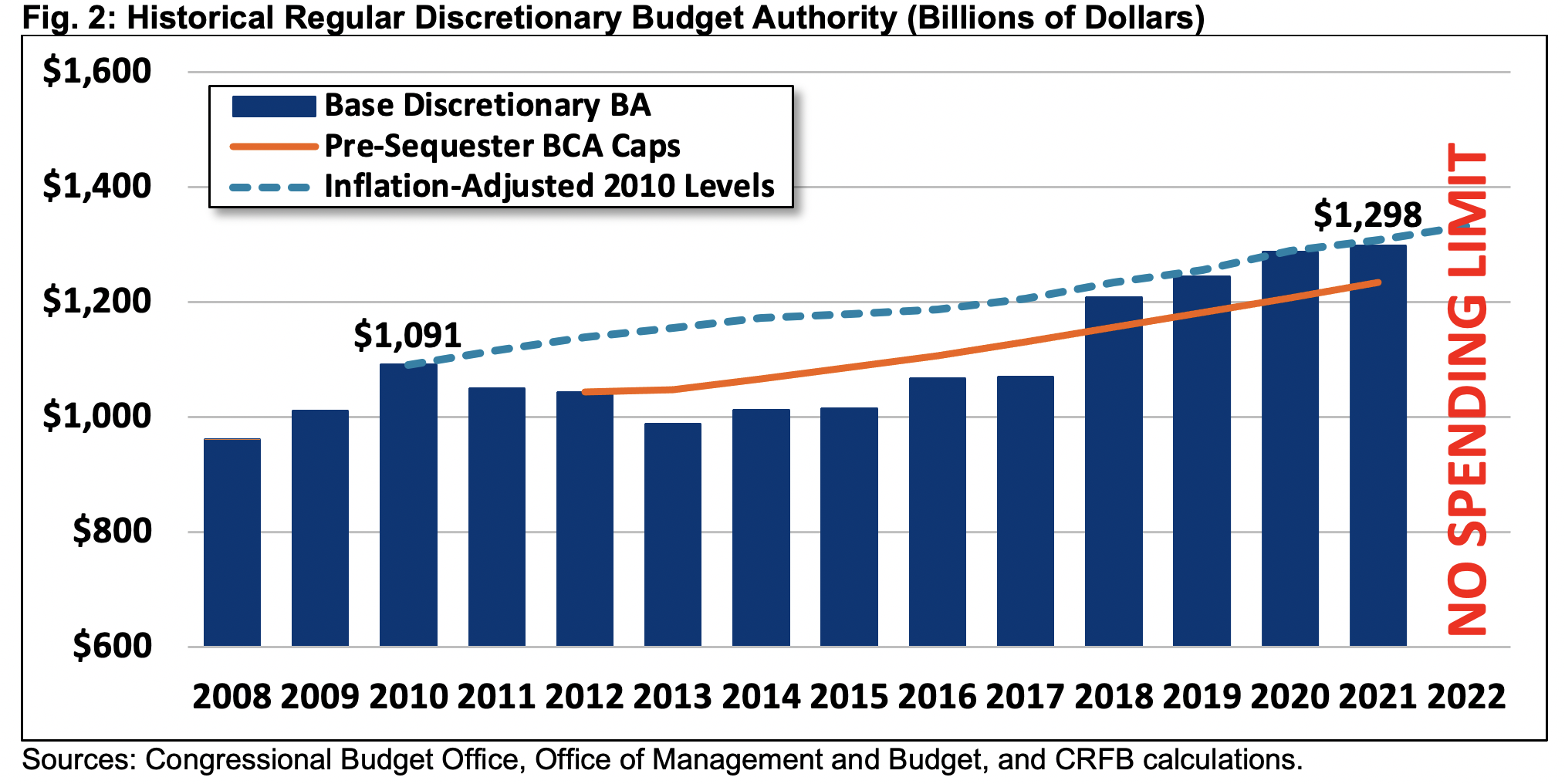

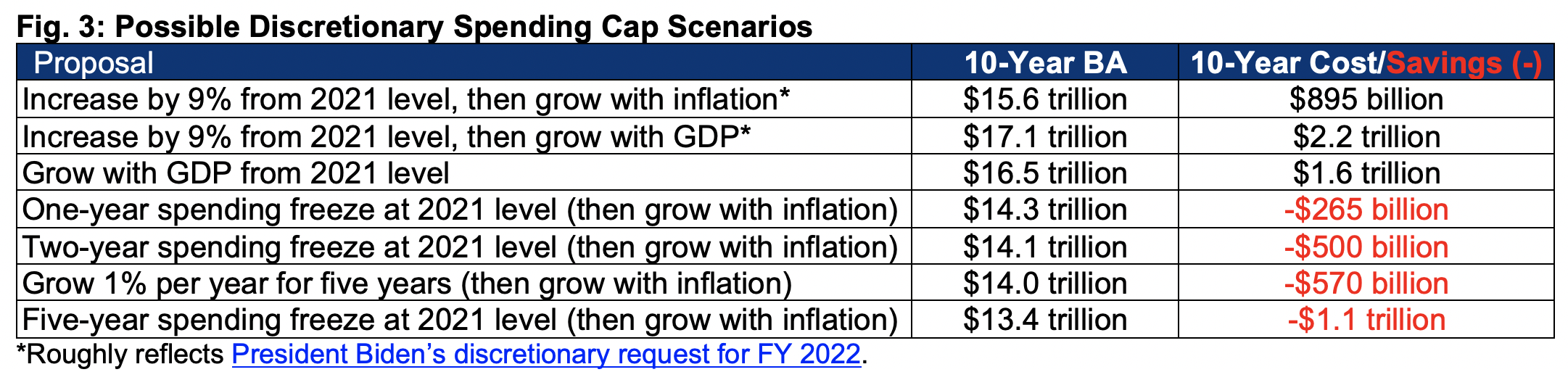

- The End of Discretionary Spending Caps: Since 2012, discretionary spending caps have been in place (though in practice, these caps have often been increased and in some instances violated). These caps expire at the end of this fiscal year, leaving appropriators without a legal constraint on discretionary spending and thus creating the opportunity for a spending free-for-all.

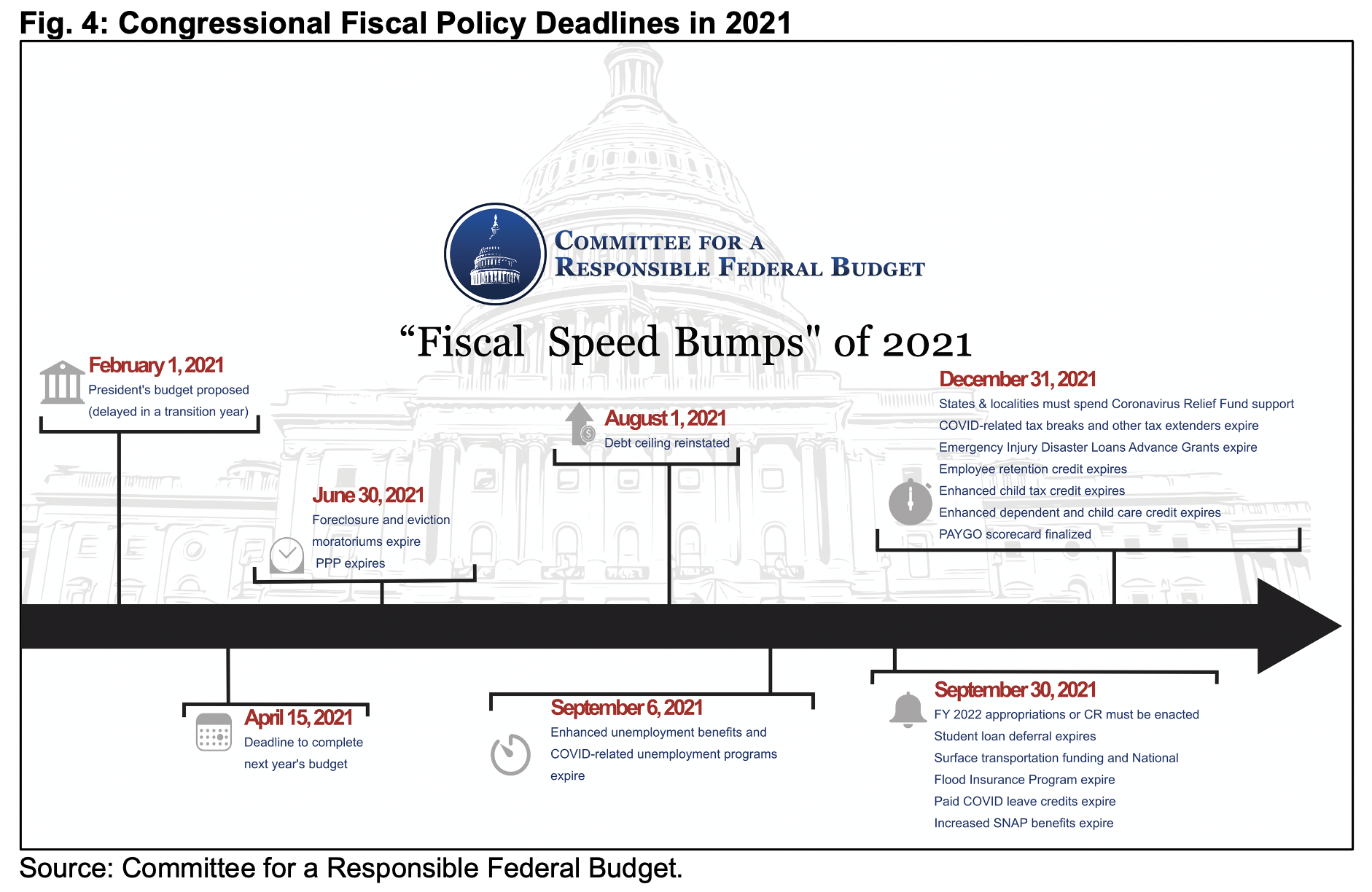

- Predictable Expirations and Fiscal Deadlines: President Biden’s agenda, like those who came before him, will be in many ways dictated by a series of expirations and deadlines. This year alone, the country will have to deal with the return of the debt limit (August 1), the end of expanded unemployment benefits (September 6), the expiration of numerous program authorizations (September 30), and the end of the expanded Child Tax Credit and other tax breaks (December 31). Policymakers must also address the statutory Pay-As-You-Go scorecard if they choose to avoid an across-the-board sequestration. Additional deadlines will present themselves in future years, including the expiration of numerous tax changes from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 by the end of 2025.

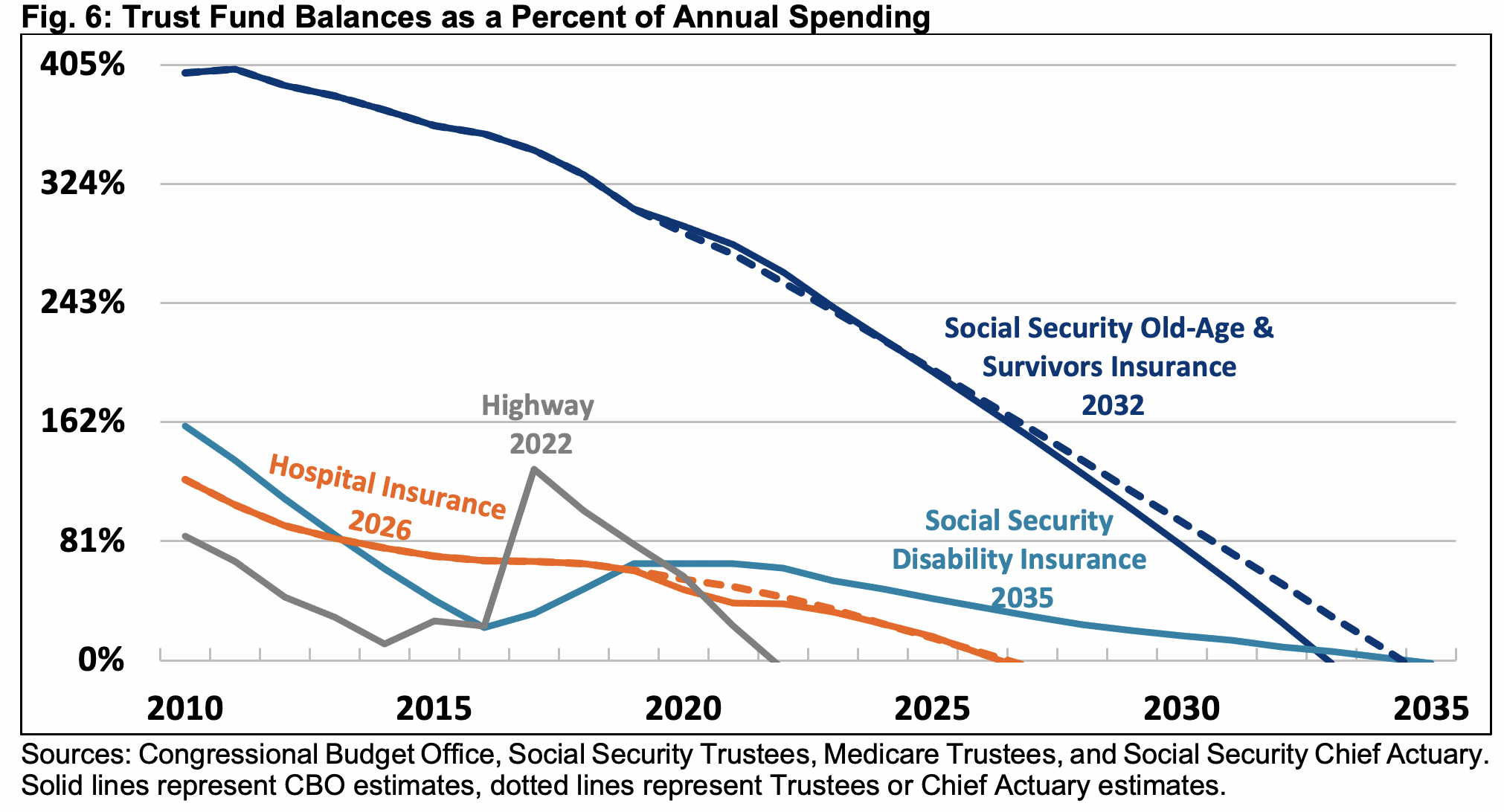

- Major Trust Funds Are Headed Toward Insolvency: Four major trust funds are projected to deplete their reserves within the next 14 years: the Highway Trust Fund in FY 2022; The Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund in FY 2026; Social Security’s retirement fund in calendar year 2032; and the Social Security Disability Insurance trust fund in calendar year 2035. Given this tight timeline, all of these trust funds should ideally be secured during President Biden’s time in office.

While all Presidents face fiscal challenges, the current outlook is unprecedented in many ways. The President and Congress should address these challenges by paying for new initiatives, stemming rising debt levels once the economy has recovered, setting reasonable spending caps, responsibly addressing various expiring policies, and securing the nation’s most important trust fund programs.

Record Debt Levels

As a result of the fiscal irresponsibility of the last several years and massive (mostly justified) short-term borrowing to fight COVID-19, President Biden inherited a debt larger than the economy and higher, in terms of a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), than any President besides Harry Truman in 1945. However, unlike during the Truman Administration – when debt declined from record levels – the debt is now projected to grow indefinitely.

Including the effects of the recently enacted American Rescue Plan, debt is projected to reach a record 108 percent of GDP this fiscal year, reach 113 percent by 2031 and become double the size of the economy by 2050. Under an alternative scenario where policymakers allow expiring tax cuts to continue and grow annual appropriations with the economy instead of inflation, debt would reach 124 percent of GDP by 2031 and 258 percent by 2051.

These high debt levels are the result of high and rising annual deficits. Under current law, the budget deficit is projected to total 15.6 percent of GDP ($3.4 trillion) this year. Over the coming decade, deficits are projected to average 4.7 percent of GDP ($1.3 trillion), reaching 5.8 percent ($1.9 trillion) by 2031. From there, the deficit will grow to 13.4 percent of GDP ($8.9 trillion) by 2051. There is no precedent for such high levels of sustained borrowing.

While near-term borrowing has helped protect the economy, high and rising debt will have considerable negative long-term consequences. High debt slows income and wage growth, increases net interest payments, reduces the fiscal space available to respond to a recession or emergency, leaves us more vulnerable to a variety of domestic and international risks, places an undue burden on future generations, and heightens the risk of a fiscal crisis.

The End of Discretionary Spending Caps

Roughly one-third of federal spending is classified as discretionary and is appropriated every year by Congress. Since 2012, defense and nondefense discretionary spending has been limited through statutory spending caps (though these limits have been adjusted and sometimes circumvented). On September 30, 2021, these caps will expire, meaning there will be no legal constraint on discretionary spending for FY 2022 or any fiscal year thereafter.

Historically, spending caps have helped to curb the growth of discretionary spending and to support the annual appropriations process, which currently requires 60 votes in the Senate. While policymakers raised these caps several times, undoing much of the savings originally outlined in the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, the caps did help limit spending for several years and may have also prevented much larger defense and nondefense spending increases from taking place.

With no caps in place starting in FY 2022, it may be difficult for policymakers to reach agreement on discretionary spending levels, potentially resulting in a fiscal free-for-all. The President and Congress should agree to a new set of caps that are both responsible and achievable.

Predictable Expirations and Fiscal Deadlines

Over the next few years, we face several predictable expirations and fiscal policy deadlines that will force congressional action. They should be dealt with responsibly.

On August 1, 2021, the debt ceiling will be reinstated at the current debt level, meaning the federal government will be unable to issue any new debt. Though the Treasury Department has tactics – known as “extraordinary measures” – to delay the need for a debt limit increase by several months, policymakers will ultimately need to either increase or again suspend the debt ceiling.

The enhanced unemployment compensation benefits authorized in COVID-19 relief legislation will expire on September 6, 2021. This includes increased weeks of benefits, expanded eligibility to cover self-employed and gig workers, and the $300 weekly benefit supplement.

At the end of this fiscal year – September 30, 2021 – current appropriations bills and spending caps will expire, requiring either a continuing resolution or new appropriations bills. In addition, a number of program authorizations expire, including for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and federal transit and highway programs. Various recession-related spending provisions will also expire, including a 15 percent increase in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) monthly benefits.

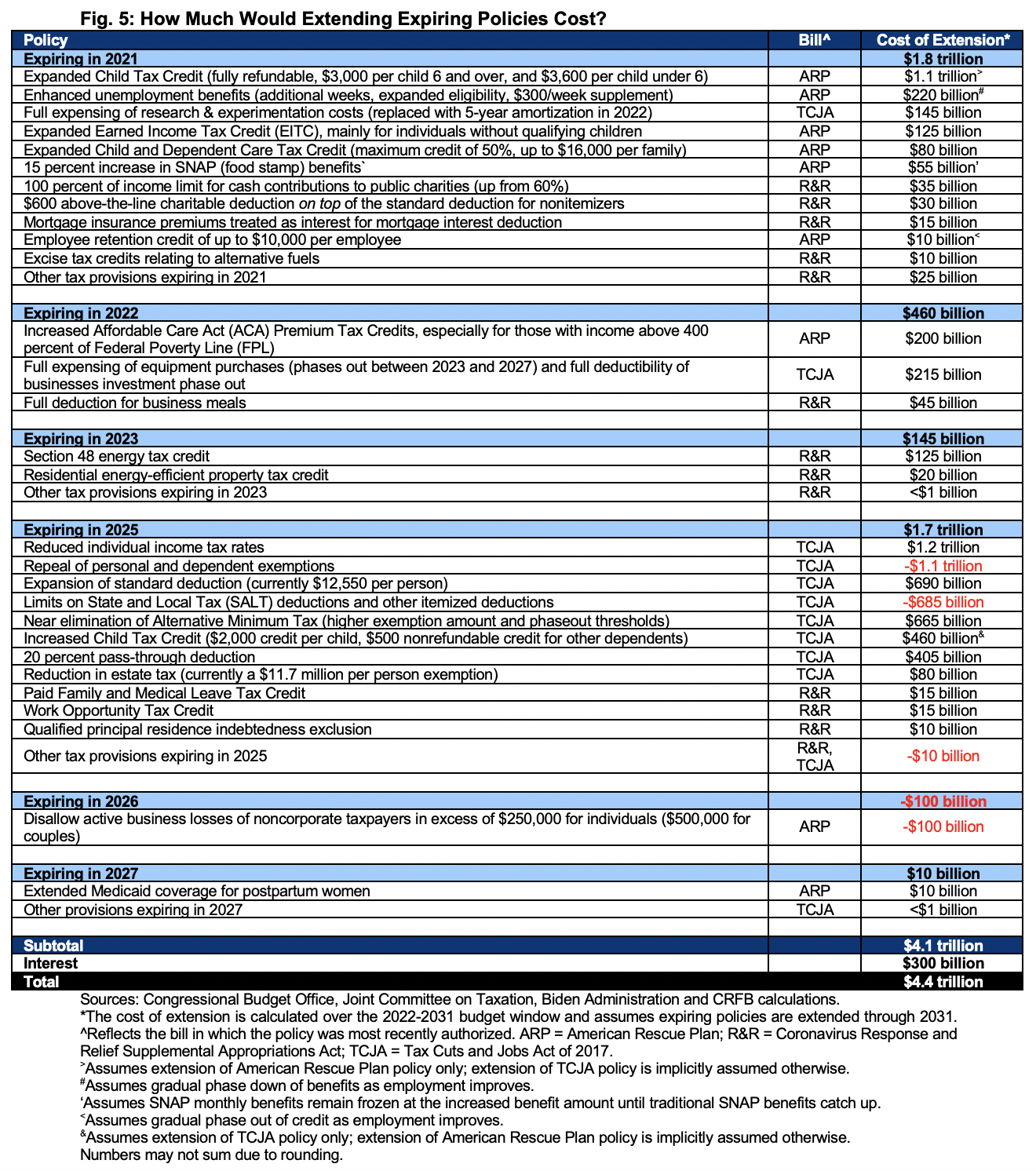

On December 31, 2021, a number of tax credits and provisions are scheduled to expire. This includes expansions of the Child Tax Credit (CTC), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit authorized in the American Rescue Plan. The Employee Retention and Paid Sick Leave tax credits – which were authorized in earlier COVID relief bills and extended in the American Rescue Plan – will expire, as will a series of temporary tax breaks known as “tax extenders.”

Finally, by the end of 2021 or very beginning of 2022, policymakers will need to address the massive debit on the Statutory Pay-As-You-GO (PAYGO) scorecard. Since the American Rescue Plan added nearly $1.9 trillion to the deficit subject to PAYGO, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) will be required to enact across-the-board cuts known as sequestration. Absent measures to wipe the scorecard clean, Medicare payments will be cut by 4 percent and spending on certain other programs – for example, agricultural support – will be cut by 100 percent.

Beyond 2021, we face or must prepare for a number of additional expirations.

Starting on January 1, 2022, businesses will be required to amortize research expenses over five years. Moreover, the health insurance premium tax credits expanded in the American Rescue Plan and the full deduction for business meals will expire on December 31, 2022. Next year will also be the final year that businesses can deduct the total cost of equipment up-front, known as “full expensing.” Full expensing will completely phase out by the end of 2026 under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA).

On December 31, 2023, a number of energy tax credits will expire, including a five-year recovery period for certain energy property and tax breaks for residential energy-efficient properties.

Nearly all of the individual income tax provisions in the TJCA, as well as other temporary tax breaks, will expire on December 31, 2025. The TCJA provisions include reduced individual income tax rates, a larger standard deduction, a new deduction for business income, limits on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and other itemized deductions, the elimination of personal and dependent exemptions, and a reduction in the income thresholds for the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) and the estate tax. The temporary tax breaks set to expire include the Work Opportunity Tax Credit, the treatment of mortgage insurance premiums as qualified residence interest, and the Paid Family and Medical Leave tax credit for employers.

If each of these policies were extended without offsets, depending on exactly how, we estimate they could increase the deficit by $4.4 trillion, including interest. By 2031, debt would reach 127 percent of GDP, 14 percentage points higher than currently projected. Blanket extensions of these provisions would obviously be a mistake.

Instead, Congress and President Biden should let many of these policies expire or take effect as scheduled, modify or phase out others, and fully offset the cost of policies they choose to extend. They should also view these various deadlines as opportunities to draw attention to the country’s immense fiscal challenges and enact reforms to put us on a more sustainable long-term path.

Major Trust Funds Headed Toward Insolvency

Under current projections, at least one major federal trust fund will become insolvent during President Biden’s current term, and a second would run out during a theoretical second term. Within the next 14 years, no fewer than four major trust funds are projected to become insolvent.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) will be exhausted in FY 2022 and the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund in FY 2026. The Social Security Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund is projected to run out in calendar year 2032 and the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund in calendar year 2035.

The Highway Trust Fund – which could become insolvent as soon as next year – faces a $195 billion shortfall over the next decade. Absent new legislation, highway and transit projects will be temporarily halted and spending will be cut by 25 percent upon insolvency. During a hypothetical second Biden term, the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund – which faces a $515 solvency shortfall through 2031 – will deplete its reserves, at which point Medicare spending will be cut by 13 percent.

Though more than a decade from insolvency, the Social Security trust funds require prompt action as well. Today’s youngest retirees will be only 73 years old when the retirement trust fund runs out of reserves, and benefits are cut across-the-board by 27 percent. Based upon current projections, the program will never pay full benefits to many workers under the age of 56.

Policymakers must act soon to identify and appropriately phase-in whatever adjustments are deemed necessary to save these important trust fund programs.

Conclusion

Once the pandemic ends and the economy fully recovers, the nation will have to prepare for the daunting set of fiscal challenges ahead. President Biden entered office facing high debt and deficits, the end of discretionary spending caps, a series of looming fiscal deadlines, major trust fund shortfalls, and no agreement on how to address these challenges.

The unprecedented challenges we face should motivate lawmakers to fully pay for all new legislation and to work together on a plan to control the growth of debt, ultimately placing it on a downward path.

We hope that once the country is on a path to recovery, our leaders will work together to improve our fiscal situation and restore fiscal sustainability. Doing so is crucial to securing both our fiscal and economic futures and will help to restore the resources and flexibility needed to address other critical priorities.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image