Tariffs Are Generating Meaningful New Revenue

On August 7, the Trump Administration finalized a new set of “reciprocal tariff rates” that generally range from 10 to 41 percent. Assuming they remain in place, these and a variety of previously implemented tariffs (including a 10 percent baseline “reciprocal tariff”) and recently-announced trade agreements are likely to generate significant revenue. Those funds should be used for deficit reduction – not new tax cuts, spending, or rebates – and those who wish to reduce or reverse the tariffs should put forward alternative sources of deficit reduction to replace them.

In this analysis, we find:

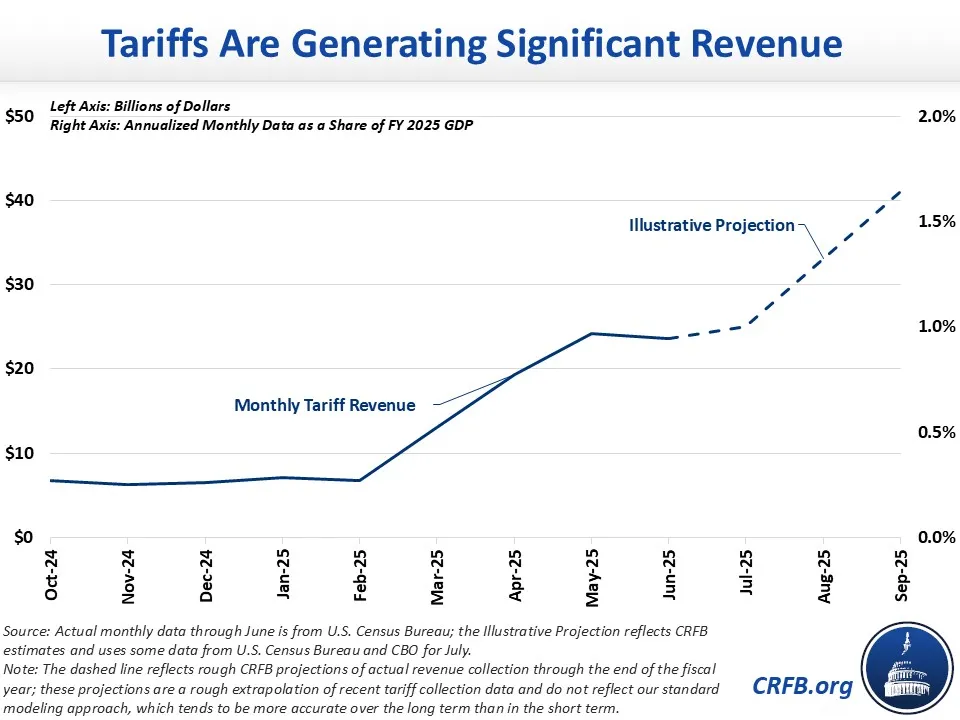

- Monthly tariff revenue has more than tripled, from $7 billion late last year to about $25 billion in July and is on course to rise substantially in the coming months.

- The new tariffs introduced by the current Trump Administration will generate an estimated $1.3 trillion of net new revenue through the end of his term and $2.8 trillion through 2034, before accounting for economic effects – about $600 billion more than the tariffs in effect as of May.

- The U.S. Trade Court has ruled some of these tariffs illegal, pending appeal. If the ruling is upheld, the remaining tariffs could raise as little as $800 billion through 2034.

- Depending on the legal outcome, recent tariff increases will generate 0.2 to 0.8 percent of GDP of net new revenue through 2034 under conventional scoring.

Note: On August 22, CBO estimated recent tariffs would generate $3.3 trillion of revenue from 2025 through 2035, which is the equivalent of roughly $3 trillion through 2034.

Importantly, our estimates are very rough and intended to reflect the general magnitude of the policies rather than precise scores, given the complexity of the tariffs and their impacts.

Estimates also exclude macroeconomic effects, which could reduce the net (real) deficit reduction from tariffs to the extent they lead to slower growth and higher inflation. Nonetheless, the recent tariff increases are likely to meaningfully reduce deficits if allowed to remain in effect or replaced on a pay-as-you-go (or Super PAYGO) basis.

Tariffs are Generating Significant Revenue

Since 1940, tariffs have generated only a small amount of revenue for the federal government. Prior to the first Trump Administration, for example, tariffs were generating about $3 billion per month. Largely due to tariffs put in place during that Administration – including on Chinese goods and steel and aluminum – monthly tariff revenue grew to about $7 billion per month in the year prior to this Administration. Since then, revenue has expanded dramatically.

Over the course of 2025, President Trump has used various executive powers to enact or increase a large number of tariffs. Through mid-May, these included a 10 percent additional baseline tariff on most imports, a 25 percent rate on automobiles and auto parts, a 25 percent tariff on steel and aluminum, a 25 to 10 percent tariff on non-USCMA goods from Canada and Mexico, and a 30 percent tariff on most Chinese goods.

Since mid-May, President Trump has announced a number of additional tariffs, either imposed unilaterally or through trade deals. These include new “reciprocal rates” for many countries that vary from 10 to 41 percent, raising the rate on steel and aluminum products to 50 percent, enacting a 50 percent tariff on copper, increasing the 25 percent rate on Canada to 35 percent, reaching a trade deal with the European Union in which most goods are tariffed at 15 percent, and announcing other trade deals with countries such as the United Kingdom, Japan, and Indonesia.

Monthly tariff revenue has grown in kind, from $7 billion (0.3 percent of GDP) per month late last year to about $25 billion (1.0 percent of GDP) in July (the total revenue impact will be smaller, as the tariffs will cause income and payroll tax revenue to decline). We expect tariff revenue to grow further and ultimately rise to $40 to $50 billion per month (over 1.5 percent of GDP), before declining some as supply chains adjust.

Through Fiscal Year (FY) 2034, we estimate these tariffs will impose an average effective tariff rate of about 17 percent. That’s up from 2.3 percent in calendar year 2024 and 1.5 percent back in 2015.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that tariffs in effect as of May 13 would generate $2.5 trillion of revenue through 2035 before accounting for economic effects, which is equal to about $2.3 trillion through 2034. We estimate the additional tariffs enacted and announced since CBO’s June score will generate another $600 billion through 2034, if they remain in effect.

In total, we estimate the tariffs will generate about $1.3 trillion over the course of President Trump’s term in office and $2.8 trillion through FY 2034, if they remain in effect. This is the equivalent of $3.1 trillion through FY 2035. These estimates are similar to Yale Budget Lab’s estimate of $2.7 trillion over ten years. Tax Foundation’s conventional revenue estimate of $2.3 trillion through 2034 differs mainly due to the inclusion of a 125 percent tariff on China, which is high enough to actually reduce revenue.

Revenue Impact of Recent Tariffs, Excluding Economic Effects

| CY 2025-2028 | FY 2025-2034 | |

|---|---|---|

| Tariffs | ||

| Tariffs in Effect on May 13 | $1.0 trillion | $2.3 trillion |

| Additional Tariffs through Aug. 7* | $0.3 trillion | $0.6 trillion |

| Total Tariffs through Aug. 7 | $1.3 trillion | $2.8 trillion |

| Tariffs if U.S. Trade Court Decision Upheld | $0.4 trillion | $0.8 trillion |

| Dynamic Revenue Impact (All Tariffs) | $0.8-$1.2 trillion | $1.7-$2.6 trillion |

Sources: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates mainly based on data from the Congressional Budget Office and U.S. Census Bureau.

Notes: Numbers are rough and rounded to the nearest $100 billion. Conventional estimates reflect the average of scenarios where lost trade is and isn’t diverted to other trading partners. Conventional estimates assume tariffs would reduce import levels consistent with elasticities derived from research and that all gained tariff revenue would be subject to income and payroll tax revenue offsets. For diversion estimates, diverted imports are subject to elasticities to the degree that tariffs on imports from other countries have also risen.

*Includes tariffs currently in effect or set to take effect under a trade deal or implementation announcement. Does not include any tariffs currently “on pause” or discussed only in concept.

On May 28, the U.S. Court of International Trade ruled tariffs enacted under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) illegal, and various states and businesses are also challenging the tariffs. A higher court ruled that these tariffs will remain in effect pending an appeal. But if the ruling that these tariffs are illegal stands and only section 232 tariffs remain in effect – including the tariffs on steel, aluminum, copper, autos, and auto parts – we estimate net new revenue would instead be roughly $800 billion through 2034.1 Revenue could be as high as $1.4 trillion if the tariffs under the new EU trade deal are also ruled legal.

Our estimates are significantly lower than what one would expect on a static basis from simply boosting the average tariff rate from 2 percent to 17 percent. That’s for two reasons. First, we estimate the tariffs would reduce the quantity (and possibly price) of imports by roughly a quarter – or $10 trillion. And second, we estimate higher tariff revenue will reduce real income and payroll tax revenue by reducing net real after-tax income.

However, our estimates do not account for macro-dynamic effects – the revenue and interest effects resulting from the impact of tariffs on the overall economy. Current and recent tariffs have been estimated to reduce expected output by 0.4 to 1.1 percent, which in turn could reduce revenue. Based on CBO, these effects could shrink the deficit impact by roughly a tenth. Based on Yale Budget Lab and Tax Foundation, the primary deficit reduction could be 17 to 40 percent smaller. Relative to our estimates, this suggests $1.7 to $2.6 trillion of primary deficit reduction (including interest rates effects) through 2034 on a dynamic basis (or about $500 to $800 billion if the trade court ruling is upheld). And these figures may not fully account for the impact of trade announcements on international relations, market uncertainty, or confidence in the dollar.

Tariffs Are Producing Meaningful Deficit Reduction

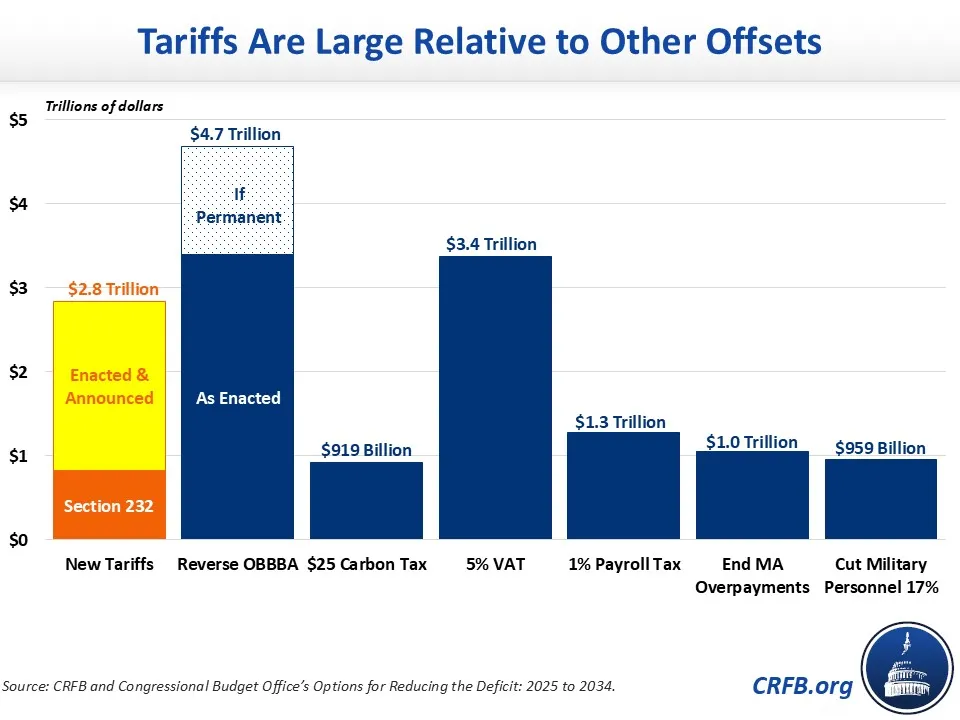

If made permanent, tariffs enacted since the beginning of President Trump’s second term will produce significant revenue through FY 2034 – $800 billion to $2.8 trillion or 0.2 to 0.8 percent of GDP, on a conventional basis. This is not as large as the $3.4 trillion primary deficit increase from the recent reconciliation law (OBBBA) – nor the $4.7 trillion increase if OBBBA is made permanent – but it is meaningful relative to many other sources of revenue or savings.

To put the tariffs in context, they are larger than what would be collected from a new 1 percent payroll tax, a $25 carbon tax, an elimination of Medicare Advantage overpayments, or a 17 percent reduction in military personnel. They are somewhat smaller than what would be collected from a 5 percent broad Value-Added Tax (VAT) or reversing the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), and they are about 60 percent the size of a permanent version of OBBBA.

Although there are many legitimate concerns over the tariffs – including their impact on the economy and the level of uncertainty they are creating – policymakers should not repeal them without an adequate replacement for the revenue loss. Nor should they divert the revenue away from deficit reduction and toward new spending, tax cuts, or rebates.

If policymakers want to remove the tariffs going forward, they should put forward alternative revenue sources or spending cuts to avoid worsening an already unsustainable fiscal outlook.

One option would be to enact a Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax (DBCFT) with a border adjustment – a consumption tax on return to capital that somewhat resembles tariffs but would have little to no effect on economic activity.

Many other revenue and spending options are also available. But with debt approaching record levels, lawmakers should not give up 0.2 to 0.8 percent of GDP in revenue without introducing an alternative.

1 This includes the expectation that the government would pay back any tariffs collected that were ruled illegal.