A Second Reconciliation Bill Should Reduce Deficits

As Congress considers the possibility of a second reconciliation bill, lawmakers should ensure it reduces deficits rather than adds to them as the first one did. One of the many disappointments of the bill was that the adopted framework was the one suggested by the Senate, which was more fiscally reckless than the framework proposed by the House.

Taking a step back, a reasonable fiscal goal is to bring deficits down to 3 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This goal has broad support and has been suggested by Treasury Secretary Bessent, President Obama when he was in office, and legendary financier Ray Dalio, among others. It is an aggressive enough goal to reassure markets, but modest enough to be politically achievable (unlike more aggressive goals such as balancing the budget). Importantly, it is consistent with stabilizing the debt as a share of GDP. Achieving it in a decade would require roughly $7.5 trillion in savings.

If there is a second reconciliation bill, it should make progress in this direction by enacting at least $600 billion of spending reductions and/or revenue increases – the difference between what the House proposed for the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and the amount that was ultimately adopted. And it should not include any policies that make the deficit worse. Savings could be achieved in several ways, including by fixing elements of OBBBA itself and enacting bipartisan proposals to reduce Medicare waste.

The Reconciliation Law Fell $600 Billion Short of Its Own Target

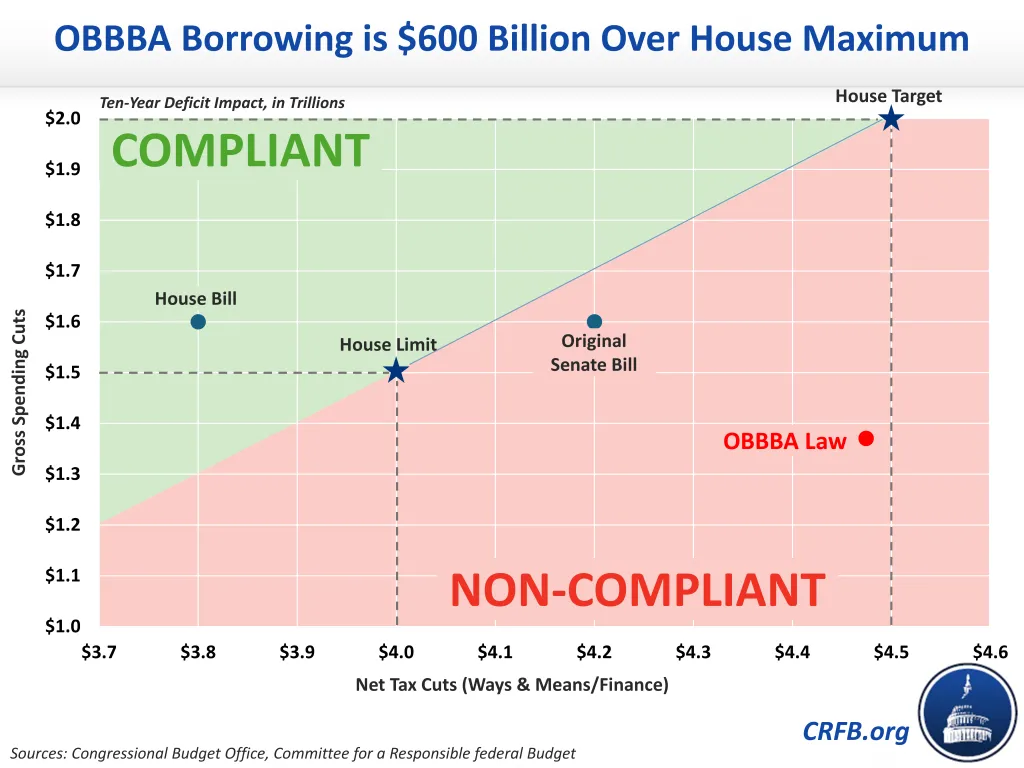

The House’s instructions in the FY 2025 concurrent budget resolution allowed reconciliation to increase primary (non-interest) deficits by up to $2.8 trillion through FY 2034. Specifically, they allowed for up to $4.5 trillion of net tax cuts and reforms and $300 billion of spending increases, offset by at least $2.0 trillion of spending reductions and related savings. They also included a mechanism to reduce the allowable net tax cuts dollar-for-dollar if spending cuts fell short of the $2.0 trillion target.

Although reconciliation should have been deficit reducing in light of our unsustainable fiscal situation, the initial House proposal did meet – and indeed beat – its $2.8 trillion target, increasing primary deficits by $2.4 trillion instead. However, the final version of OBBBA that ultimately became law increased borrowing by $3.4 trillion before interest – $1 trillion more than the initial House version and $600 billion above the maximum set by the House reconciliation instructions.

While the final version of OBBBA included almost the full $4.5 trillion of net tax cuts allowed under the House instructions, it only enacted less than $1.4 trillion of spending cuts instead of the required $2.0 trillion. The House ultimately waived its own reconciliation instructions to enact the Senate-passed legislation.

$600 Billion in Savings is an Achievable Reconciliation Target

Given that OBBBA exceeded the House’s maximum for allowed non-interest borrowing by $600 billion, policymakers should aim to save at least that much – and preferably far more – in any upcoming FY 2026 reconciliation bill.

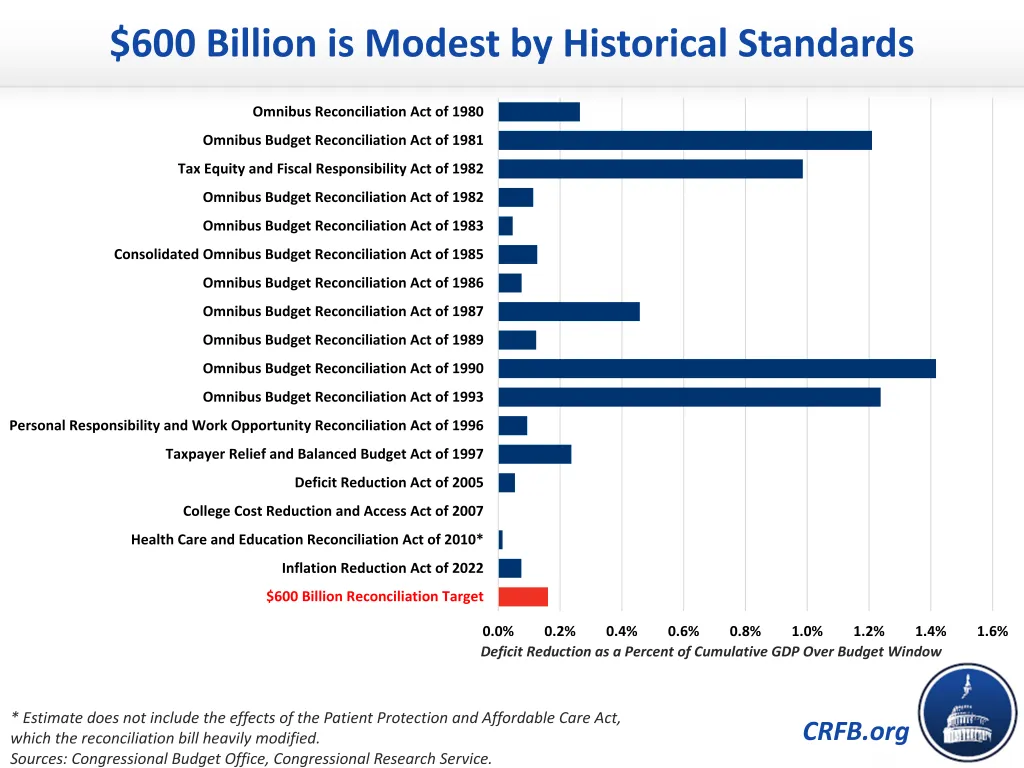

Meeting $600 billion of deficit reduction is highly achievable. It represents about one-tenth of the gross costs of OBBBA or less than one-quarter of its gross savings. At less than 0.2 percent of GDP over the coming decade, it would be smaller than seven of the 17 deficit-reducing reconciliation laws enacted since 1980 (measured as a percentage of cumulative GDP over their respective budget windows). It would only be about one-tenth as large as the 1990 budget deal.

While there are myriad deficit reduction options available to lawmakers (see our Budget Offsets Bank), the entire $600 billion in savings could potentially come from policies that were under consideration for the previous reconciliation bill but were ultimately not included in the final law.

As an illustrative example, lawmakers could save $300 billion from enacting the Same Care, Lower Cost Act (Medicare site-neutral payments) and the No UPCODE Act (Medicare Advantage reforms) – two bills discussed this summer to reduce Medicare overpayments to hospitals and insurers. They could save an additional $150 billion by adopting the original House proposals to limit the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). An additional $150 billion in savings could come from enacting policies included in the initial House version of OBBBA to reduce higher education costs, improve Affordable Care Act (ACA) program integrity, and limit new spending increases.

Illustrative $600 Billion Savings Package

| Proposal | Description | Savings (2026-2035) |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce Medicare Waste | $300 billion | |

| Adopt Site Neutral Payments | Pay the same Medicare rate to hospitals as to private clinics for nearly all Medicare services | $175 billion |

| Enact NO UPCODE to Reduce MA Risk Scores | Use two years of patient data instead of one year and exclude data from chart review and health risk assessments | $125 billion |

| Adopt House OBBBA Policies | $300 billion | |

| Adopt House AMT/SALT Policies | Revert AMT exemption to 2018 levels ($70k/$109k), limit SALT workarounds, and limit SALT deduction value to 32% rate | $150 billion |

| Make Trump ACA Enrollment Rules Permanent | Extend rules only in effect in 2026 such as standardized open enrollment, $5/month penalty for non-reverification, and eliminating full self-attestation | $50 billion |

| Restore House Higher Education Savings | Tighten Pell Grant eligibility for wealthy and part-time students, repeal in-school interest subsidy, and enact Byrd-compliant limitation on future debt cancellation | $50 billion |

| Bring New Spending Increases in Line with House | Reduce spending on farm subsidies, defense, homeland security, and Coast Guard to House levels; repeal new spending for home- and community-based care and RECA payments | $50 billion |

| TOTAL NON-INTEREST SAVINGS | $600 billion | |

Notes: Figures are rough and rounded

Sources: CRFB estimates based on Congressional Budget Office data

The House and Senate Should Set a Binding Reconciliation Target

While the House instructions in the FY 2025 concurrent budget resolution limited non-interest borrowing to $2.8 trillion, the Senate instructions allowed up to $5.8 trillion of borrowing in the name of maximum flexibility. Unfortunately, House targets in reconciliation are generally not binding and can be waived with a simple majority – as they were under OBBBA – while the Senate is required to stick to its instructions to preserve its ability to bypass the filibuster.

As Congress contemplates a second reconciliation package, lawmakers should agree to strict deficit reduction targets early in the process, which lawmakers should build into binding reconciliation instructions, particularly in the Senate. House and Senate instructions should be consistent with each other. Setting a binding target upfront would help Congress avoid the tendency to backslide and would create a common fiscal goal upon which negotiations could be based, which are often complicated by multiple committee jurisdictions and competing priorities.

$600 Billion is Not Nearly Enough

The national debt is currently as large as the economy and interest costs are surging to record highs. It would require roughly $7.5 trillion of deficit reduction to reduce annual deficits to the widely supported 3 percent of GDP target by 2035 and $9.0 trillion to simply stabilize the debt at the size of the economy.

Total Savings to Meet Fiscal Goals Under

CRFB Adjusted August 2025 Baseline

| Fiscal Goal | FY 2026-2030 | FY 2026-2035 |

|---|---|---|

| Deficit Targets* | ||

| 4 percent of GDP | $2.5 trillion | $5.0 trillion |

| 3 percent of GDP | $3.5 trillion | $7.5 trillion |

| 2 percent of GDP | $4.5 trillion | $10.0 trillion |

| Primary Balance | $3.0 trillion | $5.5 trillion |

| On-Budget Balance' | $6.0 trillion | $12.0 trillion |

| Full Budget Balance | $7.0 trillion | $15.5 trillion |

| Debt Targets | ||

| 110 percent of GDP | $0.5 trillion | $4.5 trillion |

| 100 percent of GDP | $4.0 trillion | $9.0 trillion |

| 90 percent of GDP | $8.0 trillion | $13.5 trillion |

| 80 percent of GDP | $11.5 trillion | $17.5 trillion |

Notes: All figures are rounded to the nearest $0.5 trillion. Actual ‘deficit target’ savings will depend on the deficit reduction path.

Savings targets include debt service (interest).

*Estimates assume savings begin in FY2026 and follow a path similar to offsets in OBBBA.

‘Estimates for the on-budget deficit impact of OBBBA are adjusted using data from SSA.

Failure to stem the growth in our debt will push up interest rates, slow income growth, leave less fiscal space for future emergencies, threaten national security, and increase the risk of a debt spiral and ultimately a debt crisis. Therefore, reconciliation should ideally aim to save trillions of dollars over a decade rather than hundreds of billions. And any savings not identified in reconciliation should be enacted in short order through discretionary spending caps, trust fund solutions to secure Social Security and Medicare, and further deficit reduction.

* * * * *

A $600 billion savings package is far from sufficient to put the debt on a sustainable path. But pivoting from deficit-increasing to deficit-reducing reconciliation bills could help reassure markets we are on the right path and would be an important first step toward getting our fiscal house in order.