ARCHIVE #2: How Long Before Cancelled Student Debt Would Return?

Note: This analysis has been updated from the original version to reflect new estimates of how long it would take for the amount of student debt owed to the federal government to return to $1.6 trillion if $10,000 or $50,000 of student debt is cancelled, or if all student debt is cancelled. You can read the original version here.

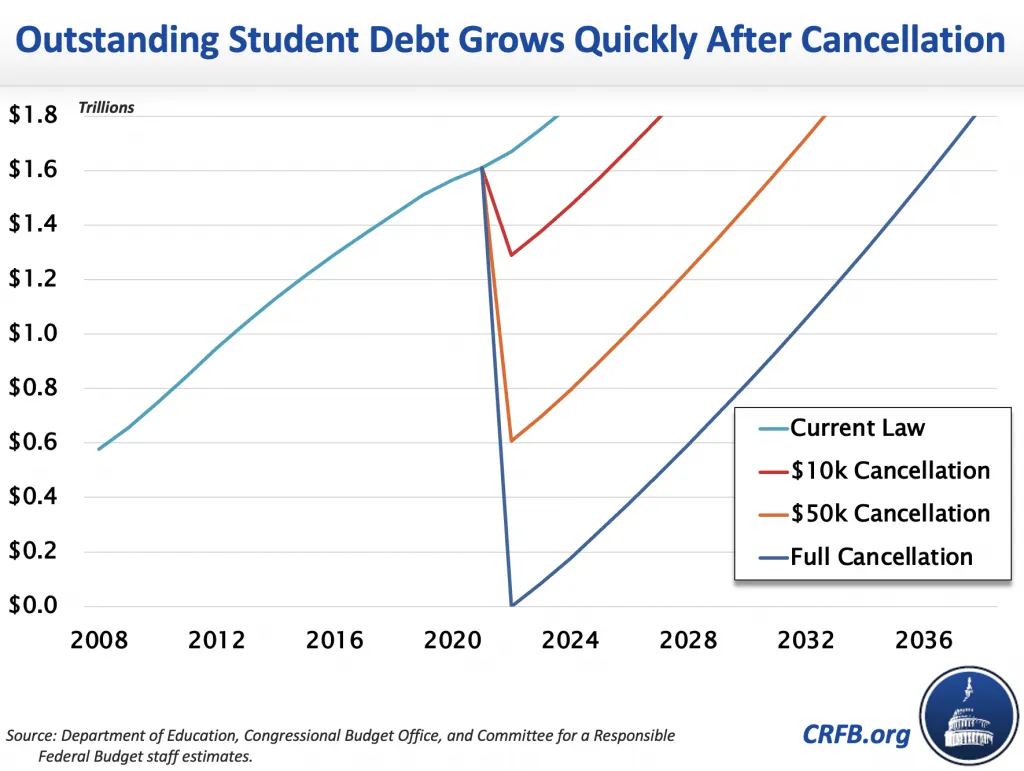

Federal student loan borrowers currently owe $1.6 trillion of student debt to the federal government. Cancelling some or all debt for current borrowers would reduce the debt burden. However, without underlying reforms to reduce the overall cost of, or the amount borrowed for, education, this reduction would only be temporary.

We estimate that absent other reforms in federal financial aid, outstanding federal student loan debt would return to the current $1.6 trillion level relatively soon after cancellation.1 With conservative assumptions, we find:

- Debt would return to $1.6 trillion four years after $10,000 per borrower was cancelled.

- Debt would return to $1.6 trillion 10 years after $50,000 per borrower was cancelled.

- Debt would return to $1.6 trillion 15 years after all debt was cancelled.

- In real dollars, student debt would return to its current level in five years after $10,000 in cancellation, 13 years after $50,000 cancelled, and 20 years after full cancellation.2

Importantly, these projections assume no change in borrower behavior. In reality, debt cancellation would likely lead to increased borrowing, slower repayment, and larger tuition increases as borrowers and schools would expect another round of cancellation in the future. Any behavioral changes would mean the portfolio would return even faster to its current size.

Projected Student Debt Growth After Cancellation

There is currently $1.6 trillion of total outstanding federal student student debt. Using data from the Department of Education, we estimate that cancelling $10,000 of student debt would reduce the portfolio to $1.2 trillion, cancelling $50,000 would reduce it to about $550 billion, and cancelling all debt would, of course, reduce the portfolio to $0. But after cancellation, the loan portfolio would grow quickly and soon return to its current level in each scenario.

Two factors drive the rapid expected portfolio growth. First, lower balances resulting from debt cancellation would also reduce the pace of repayment relative to the current student loan portfolio. We estimate that the amount would drop from $80 billion to about $60 billion in the years immediately following the $10,000 per borrower cancellation and then will slowly build back up. There is a lag in the increase in repayments because the portfolio would be comparatively younger, with a higher proportion of debt being in school or grace compared to before cancellation. For $50,000, it would drop to $25 billion, and for full cancellation, it would drop to $0.

The lower repayment amount would exacerbate the growth in the first few years because interest will still be accruing on the new loans that are not being paid back. That means faster growth for the portfolio than during normal circumstances. As a result, the more debt that is cancelled, the faster the portfolio grows after cancellation.

Secondly, new borrowing would continue to accrue at at least the previous pace (in reality, it would likely accrue faster due to moral hazard). We use the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) loan growth estimates for the next ten years. CBO projects $84 billion will be borrowed this year with increases up to $108 billion in 2032. We estimate loan growth of 2.5 percent per year thereafter.

Instead of focusing on nominal portfolio values, one could look at outstanding debt in real (inflation-adjusted) values. This becomes especially useful as we look beyond this decade, as comparing dollar values becomes less meaningful over time.

In real dollars, using the GDP deflator, we project outstanding debt would return to its current level five years after $10,000 of forgiveness, 13 years after $50,000 of forgiveness, and in 20 years after full cancellation.

Behavior Effects Will Worsen Student Debt Estimates

While our estimates show that after cancellation student debt would grow rapidly, our methodology is conservative and assumes no behavioral changes. In reality, debt is likely to increase even faster than we project due to the moral hazard effect associated with debt forgiveness.

Specifically, we expect one-time debt cancellation to lead to faster debt accumulation as borrowers expect a higher likelihood of further cancellation down the road. We expect this to manifest in two ways.

First, debt cancellation would likely lead to additional borrowing. Both non-borrowers and those borrowing below the maximum allowed (especially graduate students) may be more willing to increase their borrowing if they think there is a chance their debt will be forgiven.

Second, some borrowers would pay down their loans more slowly in hope of further forgiveness down the line. Those borrowers who are paying more than their required payment to reduce their debt, for example, are more likely to reduce their payments closer to the required amount. Others may enter Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) programs or consolidate debt in order to extend their repayment term. Absent a future jubilee, these choices would often lead to higher overall debt repayment costs due to accrued interest, but they may be advantageous if there is a reasonable chance of further debt cancellation.

These behavioral changes don’t need to be massive or widespread to meaningfully reduce the amount being repaid per year. Even if some borrowers make some adjustments, it could advance the date by which student debt returns to today’s levels.

A Short-Term Fix to a Structural Problem

We’ve previously shown that student debt cancellation would be regressive, costly, and inflationary, and this analysis shows that debt cancellation would at best be a temporary fix. Whether the federal government were to cancel $10,000 per borrower, $50,000 per borrower, or all outstanding federal student loan debt, the overall portfolio would return to its current size in a relatively short amount of time. Rather than blanket debt cancellation, policymakers should focus on reducing the cost growth associated with higher education itself. Such reforms could be coupled with targeted relief and support for borrowers and students with serious financial need or hardship.

1 To arrive at this estimate, we used a combination of our estimates for repayment with CBO’s projected growth of loan originations in the coming decade. All calculations are in fiscal years.

2 Real dollar estimate based on CBO 10-year economic estimates and CRFB modifications to the GDP deflator from CBO’s February 2021 long-term economic forecast.