Fiscal Considerations for the Future of Telehealth

Telehealth services filled crucial medical care gaps during the COVID-19 pandemic and will appropriately remain an important part of the health care system going forward. Telehealth services can increase access to timely and effective care, and, in some cases, improve the efficiency and quality of the health care system.

However, it is important that telehealth policy be designed and implemented carefully to avoid increases in utilization, misaligned provider payment incentives, fraud, and abuse.

During the pandemic telehealth largely acted as a substitute for traditional care. 1 Yet, the pandemic experience is not representative of a future where telehealth is more fully integrated into patient practice and provider business models. The United States has a uniquely poor track record when it comes to effective health care at low cost and new technologies often burden our system with rising costs.

Though telehealth has the potential to reduce some health care expenditures, both the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) project that increased use of telehealth will add to overall health care costs. 2

Based on a recent CBO score of a five-month extension of pandemic authorities, permanent expansion could cost Medicare alone $25 billion over ten years, even without expanded use. 3 As telehealth use grows, there is the potential for even greater costs in both federal health care programs and the private sector.

With policymakers rapidly approaching a decision point on the direction of telehealth policy, it is important that they take time to fully understand the health and fiscal implications of adding telehealth services to our menu of care. Rather than make permanent decisions in the coming months, any extension of telehealth authorities should have proper guardrails, checkpoints to allow for data analysis and learning, and a way to align incentives for better and less expensive care.

Much has been written on the merits and promises of telehealth. 4 The purpose of this paper is to outline key health care costs and federal budget challenges that should be considered when developing long-term regulations surrounding telehealth.

The State of Play for Telehealth Coverage

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare coverage of telehealth was very limited. Reimbursement for telehealth services was only covered for those living in rural areas with more limited access to nearby providers, and beneficiaries wishing to utilize those services were required to travel to a designated medical facility. 5 Private health insurance and Medicaid coverage was also limited, following Medicare’s lead, and often varied from state to state. In January 2020, less than 1 percent of medical services in the United States were provided through telehealth. 6

In response to the pandemic, Congress gave the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) the authority to waive restrictions on Medicare telehealth coverage for the duration of the officially declared Public Health Emergency (PHE). This new authority allowed anyone to receive services in their home, using a wide variety of audio-video technology with the option for audio-only care. It also allowed patients to see new providers rather than being required to have a preexisting relationship before permitting telehealth visits. The private sector followed Medicare’s telehealth expansion, increasing patient access and helping providers stay in business. 7

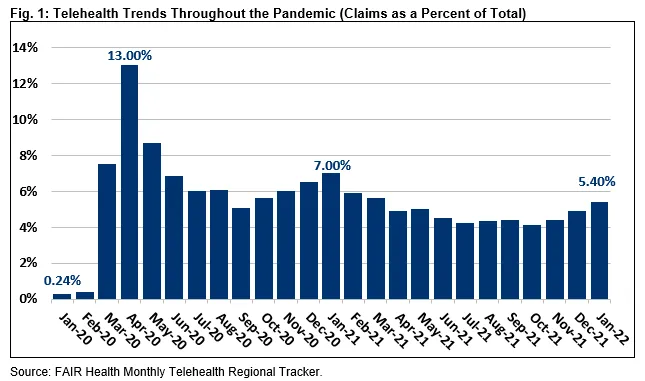

In response, overall telehealth claims rose from less than 1 percent of all claims before the pandemic to a peak of 13 percent in April 2020, settling at below 5 percent after that. 8 Medicare telehealth usage followed a similar trajectory to overall claims. 9

Telehealth waivers have been repeatedly extended along with extensions of the PHE, which can be renewed every 90 days by the HHS secretary. The most recent extension from April 16, 2022, will be in effect until July 15, 2022. Additionally, the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 omnibus appropriations bill (signed on March 15) allows for the telehealth waivers to extend 151 days after the PHE ends.

The omnibus also requires the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and the HHS Office of the Inspector General to provide an analysis and recommendations on telehealth by the middle of 2023 covering the implications of expanded Medicare coverage; utilization of services; Medicare expenditures; Medicare payment policies; program integrity risks; recommendations on preventing waste, fraud, and abuse; and other relevant topics. 10

Congress will ultimately need to determine the parameters for telehealth coverage in Medicare and Medicaid. This decision will also indirectly influence private insurance coverage decisions, although lawmakers might decide to legislate those directly. Some legislation will need to pass within five months of the end of the PHE in order to avoid a dramatic disruption in ongoing care, but there is no reason for that legislation to include permanent and blanket changes in policy. That is especially important because of the above-mentioned essential information from the mandated HHS and MedPAC reports.

The Cost Challenges of Telehealth

The promise of telehealth is that it can increase access to care. It can bring doctors to places they wouldn’t necessarily be, and it cuts out the requirement for patients to physically travel to an appointment. One study estimated that the time commitment inherent in these visits, along with the need to take off work, costs patients $89 billion a year in total lost time and wages. 11 In some scenarios, expanded telehealth may also reduce direct health care costs: for example, allowing a patient to avoid a more costly trip to a doctor’s office.

However, telehealth is likely to increase health care costs overall, especially if policymakers don’t pay special attention and care to its design. With federal and overall health care costs continuing to grow faster than the economy, these cost increases should be of particular concern.

When thinking about the long-term direction for telehealth authorities, we suggest attention to the following challenges related to the federal budget, and to national health expenditures.

- Utilization – telehealth services should ideally help reduce over-utilization of care, but could end up substantially increasing patient utilization of health care services.

- Provider incentives – telehealth services should ideally help providers reduce the cost of care, but payment incentives might lead to more costly care – especially if telehealth services continue to be reimbursed at parity with in-person care.

- Fraud and abuse – telehealth services are at particular risk for fraudulent billing.

Below, we discuss each of these challenges and the opportunities for policymakers to address them through caution and guardrails.

The Risk of Increases in Utilization

The easier it is to access a given health intervention, the higher utilization is likely to be. Conversely, increased friction through high deductibles or increased cost-sharing reduces utilization. 12 Depending on the quality of care, higher utilization may improve, worsen, or have little effect on health outcomes; but it will nearly always result in higher costs.

Thus, it is very likely the case that an expansion of telehealth, by removing some of the friction from provider-patient interaction, will lead to increased utilization. This will be the case in the aggregate, despite there being some circumstances where a telehealth appointment might allow a patient to avoid a longer or more intensive interaction with the health care system. 13

To be sure, there is evidence that telehealth during the pandemic primarily substituted for in-person care. 14However, the circumstances were obviously unique, and that evidence is hardly generalizable to a future health care system where telehealth is more integrated into care and patients are used to relying on the easy access technology provides. One survey suggests three-quarters of patients anticipate continuing the use of telehealth for at least some of their care. 15

Policymakers will need to manage the transition to telehealth to avoid excessive increases in utilization. Unfortunately, policymakers are often unwilling to follow through on restrictions.

An example from the pandemic is illustrative. The CARES Act allowed those in high-deductible plans tied to Health Savings Accounts to receive telehealth services without having to meet their deductibles – even though these deductibles are core to the benefit design of such plans (which are meant to control cost growth). 16 Rather than allow this emergency measure to expire as intended at the end of 2021, Congress revived the waivers in the recent omnibus bill, extending them through the end of 2022.

Not only does this choice drive up overall utilization of care but adds unjustified incentives to specifically increase utilization of telehealth services, which are given a financial advantage over in-person care. Policymakers should avoid creating these perverse incentives when designing a new telehealth regime.

The Problem of Payment Incentives and Payment Parity

The decisions providers make as telehealth expands have important implications for growing health care costs. In the United States’ health care system, doctors and hospitals have substantial influence on the volume, intensity, and price of care – more so than patients do in most cases. 17

Avoiding dramatic increases in provider-led utilization will be especially important in government programs like Medicare, which have few mechanisms for managing care. Already, utilization in fee-for-service Medicare is slated to grow nearly 4 percent per year through 2030 when adjusted for demographics. 18

To avoid further driving up health care costs, an expansion of telehealth would ideally occur only within the context of a shift away from fee-for-service payment to alternative payment models like Accountable Care Organizations. Such value-based payment (VBP) approaches could be an opportunity to maximize the opportunities of telehealth without substantially increasing spending. 19 VBP could also create guardrails for providers to promote quality care through telehealth in a manner that is good for patients’ health while protecting Medicare from a payment system that promotes volume in the maximization of profits.

The goal is to avoid falling into the trap of misaligned provider payment incentives that increase provider revenue and increase national health expenditures, on top of the system-wide problems inherent in fee-for-service payment 20 and provider pricing power. 21

Examples explored by our Health Savers Initiative, like site-of-service-based payment, Part B drug ad-on fees that promote higher-priced drugs, and insurance plan gaming of risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage all demonstrate the same design flaw. Payment policies legislated to achieve worthwhile goals created misaligned incentives, yet the ability of the executive branch to re-align incentives was limited by that legislation, and Congress became hesitant to revisit the policies because the interest groups profiting from the incentives lobby them to avoid changes.

Thus, getting incentives right for telehealth, and, perhaps, more importantly creating the means or action-forcing ability to review them regularly, will be crucial to limiting any negative fiscal impact. As providers have the time to create new telehealth business models and build technological capacity, provider payment incentives should bend providers towards value, substitution, and quality.

It is especially important that policymakers resist calls for mandating permanent payment parity, where telehealth visits are paid at the same rate as in-office visits. Doing so would drive up overall health care costs, undermine any potential telehealth might have to reduce costs in select circumstances, and be highly problematic for the goal of appropriately aligning incentives.

Parity is problematic because just like on the patient side, telehealth is a form of care that should have less friction for the provider. Theoretically, the time spent by a provider interacting with a patient during a telehealth appointment might be similar to an in-person visit. However, there are numerous other ways in which telehealth can be less burdensome on a provider’s time and resources. 22 And, as groups of providers utilize telehealth more, there will be opportunities to get paid for shorter, follow-up interactions – some of which might be happening in the current system without payments attached.

The physician fee schedule in Medicare already accounts for the overhead costs to providers. So, separating payments as telehealth expands can still consider the costs of maintaining telehealth technology while incorporating any overhead savings.

The Special Case Of Mental Health Coverage

There are unique advantages to using telehealth as part of mental health care due to the general ability for such care to be provided virtually, along with the regular and frequent cadence of care being integral to a patient’s care plan. However, there are important considerations for when a care plan might require in-person patient-physician interactions.

For instance, some conditions related to mental health care can best or only be diagnosed through in-person contact. 23 Also, the pandemic experience has shown that those with the most serious mental health issues tend to use telehealth visits at a lower rate than in-person care. 24

The specific opportunities and challenges for tele-mental health, along with the increases in mental health demands due to the pandemic, have already led policymakers to create a slightly different set of rules. In 2021, lawmakers permanently authorized tele-mental health services to be provided in the home, though only after prior in-person interaction, and then in conjunction with in-person visits. 25 These requirements, supported by MedPAC, are meant to provide safeguards against inappropriate use and prevent solicitation of unneeded mental health care. 26

The President’s FY 2023 budget supports extending Medicare coverage of tele-mental health beyond the pandemic, along with numerous other mental health initiatives and investments. Some of these priorities include reducing barriers to care, ensuring coverage by private plans, and delivery across state lines. 27 The Senate Finance Committee also intends to propose mental health legislation over the summer. 28 In March, the committee released a report on mental health care that dives into the impacts of the pandemic, what was done with respect to telehealth, the urban-rural divide, and disparities in access. It signaled support for both eliminating in-person visit requirements for mental health services and coverage of audio-only services. 29

Lawmakers should follow CMS’s lead on guardrails and not rush to make permanent rules on issues still being studied. The renewed attention on the need for better mental health care and increasing access to care is an important development, with the caveat that the longer-term problem of practitioner scarcity is not solved by such increases in access.

Having as much data for policymakers as possible will be essential before they rush to change the current rules and guardrails. They need to understand who uses tele-mental health care and when in-person visits are crucial for quality care, along with the results from studying new audio-only service-level modifiers to determine how audio-only mental health impacts quality, access, and utilization. As with other types of care, it is also important to consider utilization, provider incentives, and risks of fraud and abuse – which can drive up costs without improving quality.

New Opportunities for Fraud and Abuse

With new avenues for care come more opportunities for fraud and abuse. 30 Since telehealth's entrance into the health care market, overall recoveries in health care fraud have doubled from $2.6 billion in FY 2019 to over $5 billion in FY 2021. 31

According to the American Bar Association, potential problems include up-coding time and complexity; misrepresenting the virtual services being provide; billing for services not rendered; and kickback schemes that spread profit from unnecessary tests, medications, and equipment. 32

While there are existing statutes making these acts unlawful, there must be guardrails in place to make misuse more difficult and easier to discover. MedPAC has already suggested some ways to accomplish this, such as additional scrutiny to outlier clinicians who bill many more telehealth services per beneficiary than other clinicians and prohibiting “incident-to” billing for telehealth services provided by any clinician who can bill Medicare directly. 33

MedPAC holds additional concerns with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) allowing clinicians to provide direct supervision through audio-only telehealth, which was originally put into place to limit COVID-19 exposure. The concerns are not only that it could limit quality and increase spending, but also that it may impose a safety risk because with one clinician supervising many individuals in different locations, there is an increased difficulty in addressing urgent needs. 34 This rule remains in effect until the end of the year that the PHE ends. 35

Permanent coverage for audio-only communication needs to also have limitations to ensure that it can serve as a benefit for those without access to video or in-person care, without allowing provider preference or skimping to perpetuate inequities or gaming. 36

Another concern with audio-only telehealth is its use in determining Medicare Advantage diagnostic risk scores. Those scores are already subject to gaming and have led to vast plan overpayment. 37 The HHS Office of the Inspector General has found that in-home Health Risk Assessments are problematic as a locus for coding intensity and MedPAC has suggested that diagnosis from these visits be excluded from risk scores. 38 Permitting diagnoses from audio-only interactions would clearly amplify the gaming problem.

That is why a study of these communications, their evolution, and differences in care quality will be essential. One key step taken by CMS in its 2022 Payment Policies rule was to create an audio-only claims identifier to identify mental health services delivered through telehealth. 39

There is also precedent for in-person requirements as a condition for reimbursement to reduce fraud. Such current requirements for home health services and durable medical equipment have resulted in $2 billion in savings to Medicare between 2010 to 2019. 40

Conclusion

Health care, even beneficial care, is not free. Increases in costs are passed along to employees and Medicare beneficiaries in the form of higher premiums and to taxpayers through additional Medicare and Medicaid spending, higher insurance subsidies through the tax code, or more borrowing through the national debt.

How much telehealth expansion will cost the federal government must be taken seriously. In addition to waiting for the data and research to decide what permanent decisions to make on telehealth authorities, having circuit breakers in the process for re-evaluating will be important from both a regulatory standpoint and a fiscal one. A large and bipartisan group of lawmakers have advocated for a two-year extension of telehealth waivers. 41 MedPAC has also suggested this time frame. This should be the maximum extension Congress considers, ideally including mental health in the more limited extensions.

Because telehealth as a mode of care is here to stay, the argument that authorities need to be made permanent in order to convince providers to invest in technology is not convincing. 42 Instead, the occasional expiration of authorities will provide policymakers the opportunity to review research into telehealth’s impact on health care costs. That way, it will be possible to pair extensions with other health care cost reductions. There are numerous ways to control health care costs and using the opportunity of expanding benefits is a natural opportunity to enact cost controls.

Telehealth has become an essential tool for the delivery of health care services for millions of Americans. Congress should take the time to develop comprehensive and sound legislation that would improve accessibility, but provide proper safeguards that protect patients and federal spending levels. It is ideal for short-term legislation to include components to ensure fraud protection, include studies to gather the impact telehealth has made on health care access and delivery, and give Congress time to further debate the issues.

Endnotes

1 Lok Wong Samson, Wafa Tarazi, Gina Turrini, and Steven Sheingold. “Medicare Beneficiaries’ Use of Telehealth in 2020: Trends by Beneficiary Characteristics and Location.” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Accessed April 6, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/medicare-beneficiaries-use-telehealth-2020.

2 “H.R. 2471, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022.” Congressional Budget Office, March 14, 2022. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57928; “Medicare and Medicaid: Covid-19 Program Flexibilities; Considerations for Their Continuation.” U.S. Government Accountability Office. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-575t; “H.R. 5201, Telemental Health Expansion Act of 2020.” Congressional Budget Office, December 4, 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56874.

3 CBO scored five months of expansive telehealth authorities as costing $663 million (see “H.R. 2471, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022.”) Assuming that cost remains constant as a share of Medicare Part B spending, it would total nearly $25 billion through fiscal year 2031.

4 Arielle Kane and Charlie Katebi, “Telehealth Saves Money and Lives: Lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Progressive Policy Institute, November 10, 2021, https://www.progressivepolicy.org/publication/telehealth-saves-money-an…; Wyatt Koma, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman, Medicare and Telehealth: Coverage and Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Options for the Future. Kaiser Family Foundation, May 19, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-and-telehealth-covera…; Jacob C. Warren and K. Bryant Smalley, “Using Telehealth to Meet Mental Health Needs During the COVID-19 Crisis.” The Commonwealth Fund, June 18, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/using-telehealth-meet-mental….

5 Pipes, Sally. “Don't Dam the Telehealth Flood.” Forbes Magazine, March 2, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sallypipes/2022/02/28/dont-dam-the-telehea….

6 “States' Actions to Expand Telemedicine Access during COVID-19 and Future Policy Considerations.” Commonwealth Fund, June 23, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/jun/sta….

7 Primary care physicians have cited increased reimbursement rates for telehealth, by both CMS and private insurers, as a key change that allowed them to remain open during the pandemic. See: “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Primary Care Practices.” RWJF, February 3, 2021. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2021/02/impact-of-the-covid-19….

8 “Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker: Fair Health,” Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker, FAIR Health, accessed April 7, 2022. https://www.fairhealth.org/states-by-the-numbers/telehealth.

9 “Medicare telehealth visits increased from 84,000 in 2019 to 52.7 million in 2020. In just the first month-and-a-half of the pandemic, the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries utilizing telehealth services increased 11,718 percent. See: Samson, Lok Wong, ASPE, December 2021; Pifer, Rebecca. “Medicare Members Using Telehealth Grew 120 Times in Early Weeks of Covid-19 as Regulations Eased.” Healthcare Dive, May 27, 2020. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/medicare-seniors-telehealth-covid-c….

10 “Spending Deal Asks HHS to Study Telehealth Use, Recommend Reforms.” InsideHealthPolicy.com. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://insidehealthpolicy.com/inside-telehealth-daily-news/spending-de….

11 “Travel and Wait Times Are Longest for Health Care Services and Result in an Annual Opportunity Cost of $89 Billion.” Altarum, February 22, 2019. https://altarum.org/travel-and-wait.

12 For example, research shows that delays in seeking care increase at the age of 64, and doctor visits jump at age 65, when the population nears and then becomes eligible for Medicare. Evidence from the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of health insurance is similarly persuasive. The reverse also holds true. Increased friction through high deductibles or increased cost-sharing reduces utilization, leading to lower spending levels and restrained cost growth. Even administrative burdens serve as dampers on utilization on par with financial barriers. See in order: Molly Frean, and Mark Pauly. “Does High Cost-Sharing Slow the Long-Term Growth Rate of Health Spending? Evidence from the States.” NBER, October 15, 2018. https://www.nber.org/papers/w25156; and “Does Health Insurance Affect Health Care Utilization and Health?” NBER. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www.nber.org/bah/2004number1/does-health-insurance-affect-healt….; Jonathan Gruber and Benjamin D. Sommers. “Fiscal Federalism and the Budget Impacts of the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid Expansion.” NBER, March 16, 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26862; Joseph Santos, and James C. Capretta. “National Health Expenditure Report Shows We Have Not Solved the Cost Problem: Health Affairs Forefront.” Health Affairs, December 6, 2017. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20171205.607294/full/; Austin Frakt. “U.S. Health Care Costs a Lot, and Not Just in Money.” The Incidental Economist, September 7, 2021. https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/u-s-health-care-costs-a-lo….

13 Neil Ravitz, MBA. “The Economics of a Telehealth Visit: A Time-Based Study at Penn Medicine.” Healthcare Financial Management Association. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www.hfma.org/topics/financial-sustainability/article/the-econom….

14 Kara Gavin, “Telehealth Continues to Substitute for in-Person Care among Older Adults, but Rural Use Lags.” Health News, Medical Breakthroughs & Research for Health Professionals, October 15, 2021. https://labblog.uofmhealth.org/lab-notes/telehealth-continues-to-substi….

15 “Telemedicine Won't Just Be a Pandemic Trend.” Advisory Board, February 18, 2022. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2022/02/18/telemedicine.

16 Sara Hansard, “Employers Push for Renewal of Expired Covid Telehealth Waiver.” Bloomberg Law, January 28, 2022. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/employers-push-fo….

17 “The Prices That Commercial Health Insurers and Medicare Pay for Hospitals' and Physicians' Services.” Congressional Budget Office, January 20, 2022. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57422.

18 Michael E. Chernew and J. Michael McWilliams. “The Case for ACOs: Why Payment Reform Remains Necessary.” Health Affairs Forefront, January 24, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220120.825396/; “The 2021 Report of the Medicare Trustees.” CMS. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/OACT/TR/2021.

19 Ibid.

20 Anne M. Lockner “Insight: The Healthcare Industry's Shift from Fee-for-Service to Value-Based Reimbursement.” Bloomberg Law, September 26, 2018. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/insight-the-healt….

21 Glenn Melnick, PhD;Katya Fonkych. “An Empirical Analysis of Hospital ED Pricing Power.” AJMC. MJH Life Sciences. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www.ajmc.com/view/an-empirical-analysis-of-hospital-ed-pricing-….

22 Ravitz, “The Economics of a Telehealth Visit: A Time-Based Study at Penn Medicine.”

23 Reeves JJ, et al. “Telehealth in the COVID-19 Era: A Balancing Act to Avoid Harm.” J Med Internet Res 2021; 23(2): e24785. https://www.jmir.org/2021/2/e24785.

24 Jane M. Zhu, et al. “Trends In Outpatient Mental Health Services Use Before And During The COVID-19 Pandemic,” Health Affairs, April 2022. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01297.

25 CMS has currently set those intervals at six months after the first telehealth visit, and then within 12 months after that visit. They also allow those in-person visits to be with any clinician in the same provider group to more easily meet the requirement.

26 Michael E. Chernew to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, “RE: File code CMS-1751-P” MedPAC Public Comment, September 9, 2021, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/09092021_PartB_CMS175….

27 U.S President, Fact Sheet, “President Biden to Announce Strategy to Address Our National Mental Health Crisis, As Part of Unity Agenda in his First State of the Union” White House, March 01, 2022. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/….

28 Dorothy Mills-Gregg, “Wyden Tasks Bipartisan Duos To Craft Mental Health Bill By Summer” InsideHealthPolicy.com, February 8, 2022. https://insidehealthpolicy.com/daily-news/wyden-tasks-bipartisan-duos-c….

29 U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Finance “Mental Health Care in the United States: the Case for Federal Action, 117th Cong., 2d sess., 2022. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SFC%20Mental%20Health%20Re….

30 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, March 2021 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 15th, 2021 https://www.medpac.gov/document/march-2021-report-to-the-congress-medic….

31 Over the last two years, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced criminal charges against 86 medical providers accounting for over $4.5 billion in losses from telehealth fraud and 138 medical providers accounting for over $1.4 billion in losses, with $1.1 billion of that being from telehealth fraud. See in order: “Justice Department Recovers over $3 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2019.” The United States Department of Justice, January 21, 2020. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-3-billi…; “Justice Department's False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $5.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2021.” The United States Department of Justice, February 2, 2022. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-s-false-claims-act-se….

32 Miranda Hooker, Allison DeLaurentis, Sharon Klein, and Jason Kurtyka, “Fraud Emerges as Telehealth Surges” The White Collar Crime Committee Newsletter, American Bar Association, 2021. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/criminaljustic….

33 Incident-to billing is billing for services that are provided by a non-physician practitioner, such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants, under the supervision of a physician being billed to Medicare under the physician‘s identification number. See: Miranda Hooker, Allison DeLaurentis, Sharon Klein, and Jason Kurtyka, “Fraud Emerges as Telehealth Surges” The White Collar Crime Committee Newsletter, American Bar Association 2021, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/criminaljustic….

34 “March 2021 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy.”

35 Chernew, “RE: File code CMS-1751-P.”

36 Limited access to broadband and adequate technologies poses a significant barrier to accessing telehealth. In a survey conducted by the Bipartisan Policy Center, 45 percent of rural respondents reported technical issues when accessing telehealth and 35 percent reported broadband was an obstacle. Congress has taken action to expand broadband access through their passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in November 2021, which included $65 billion in federal funding for broadband expansion, including improving broadband infrastructure and affordability. See: Jazmyne Sutton, “Telehealth Visit Use Among U.S. Adults” Bipartisan Policy Center (slideck), August 2021, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2021/08….

37 Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “Reducing Medicare Advantage Overpayments” February 23, 2021, https://www.crfb.org/papers/reducing-medicare-advantage-overpayments; Richard Gilfillan, and Donald M. Berwick, “Medicare Advantage, Direct Contracting, and The Medicare ‘Money Machine,’ Part 1: The Risk-Score Game” Health Affairs, September 29, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210927.6239/.

38 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, “Billions in Estimated Medicare Advantage Payments From Diagnoses Reported Only on Health Risk Assessments Raise Concerns”, OEI-03-17-00471, September. 2020 https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-03-17-00471.pdf; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, March 2021 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 15th, 2021, page 352. https://www.medpac.gov/document/march-2021-report-to-the-congress-medic…; Chernew, “RE: File code CMS-1751-P.”

39 Pipes, “Don't Dam The Telehealth Flood.”

40 “Medicaid Program; Face-to-Face Requirements for Home ...,” Federal Register, February 2, 2016, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/02/02/2016-01585/medicai….

41 Brian Schatz and Roger Wicker et al. to Senate Leadership “Calling For Permanent Expansion Of Telehealth Following COVID-19 Pandemic.” Congressional Letter, June 15, 2020. https://www.schatz.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Letter%20to%20leadership_CO….

42 Private insurers are expanding their telehealth offerings. Throughout 2021, 65 percent of employers with 50 or more employees that covered telehealth services made changes to their coverage in order to expand benefits. It is projected that by 2027, the telehealth sector will bring in $20 billion in revenues for technology companies and equity funding has already reached close to that. See: Kaiser Family Foundation, “Section 13: Employer Practices, Telehealth and Employer Responses to the Pandemic” 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey Nov 10, 2021. https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2021-section-13-employer-practi…; Bloomberg Intelligence, “Telehealth Sector Projected to Bring in up to $20 Billion in U.S. Revenue by 2027” Press Announcement, February 24, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/telehealth-sector-projected-to-….