Social Security General Revenue Funding Would be a Costly Mistake

The Social Security retirement program is only seven years from insolvency, at which point the law calls for a 24% across-the-board benefit cut – an $18,400 cut for a typical couple retiring in 2033. Some have suggested avoiding these cuts by funding Social Security’s deficits out of general revenue – either through borrowing, transferring, or re-allocating existing general funds.1 This would be a costly mistake.

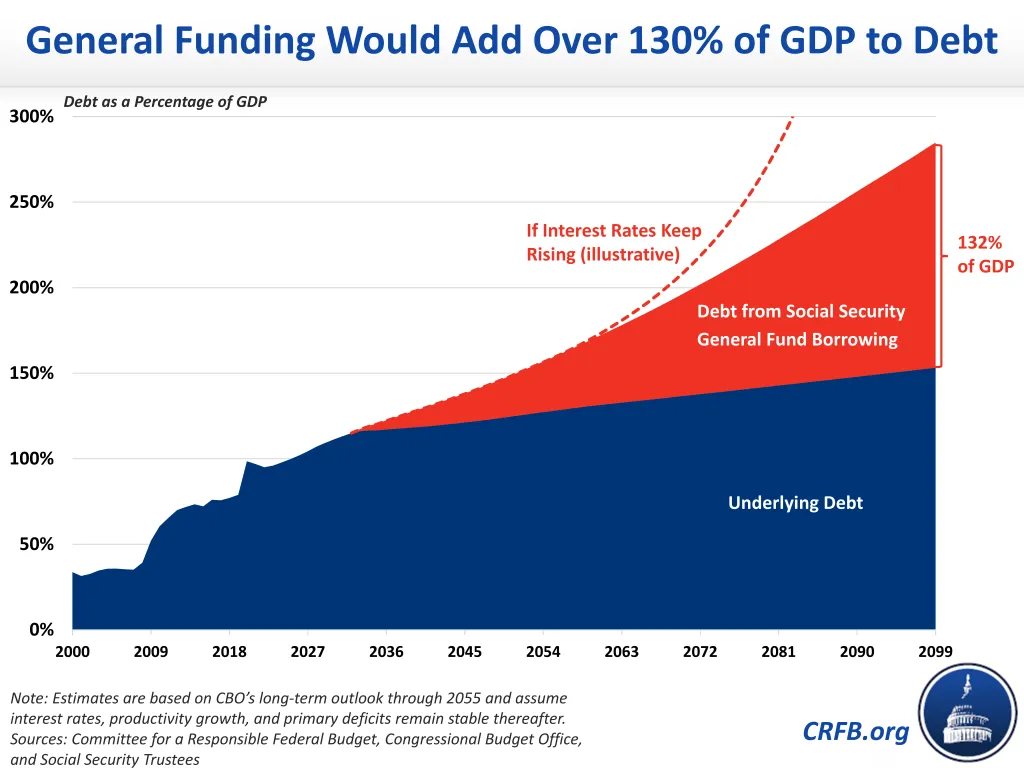

In this piece, we show that over 75 years, borrowing to fund Social Security could:

- Add over $150 trillion to the debt when adjusted for inflation, or over $700 trillion nominally

- Boost debt by over 130% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – doubling debt as a share of the economy and potentially triggering a debt spiral or fiscal crisis

- Cause interest rates to rise by 2.6 percentage points and slow income growth

- End Social Security’s current structure as a self-financed contributory program

- Erode one of the last remaining fiscal rules

General Revenue Funding Would Massively Add to the Debt

Social Security benefits are funded primarily from payroll tax revenue. The program is not allowed to spend more than it generates in dedicated revenues except to the extent it can draw from its trust fund – where prior-year surpluses are deposited and accumulate interest. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund is projected to run out of reserves in late 2032, at which point benefits must be cut by about one-quarter to match incoming revenues.

If policymakers were to change the law to allow Social Security to spend beyond its dedicated revenue – whether through a general revenue transfer or other means – it would result in a large amount of new borrowing.

Based on projections from the Social Security Trustees, fully funding benefits with general revenues would require $736 trillion of additional nominal borrowing, absent new taxes or spending cuts. Adjusted for inflation, this totals $164 trillion. And on a present value basis, discounting the future based on interest rates, it would mean adding $27 trillion to the debt. That’s the equivalent of nearly doubling today’s debt levels.

Borrowing Needed to Fund a General Revenue Transfer to Social Security (2025-2099)

| CBO | Trustees | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal Borrowing | $520 trillion | $736 trillion |

| Real (inflation-adjusted) Borrowing | $117 trillion | $164 trillion |

| Present Value Borrowing | $38 trillion | $27 trillion |

| Borrowing as a Percentage of Final Year GDP | 132% | 135% |

Sources: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Congressional Budget Office, and Social Security Trustees

Using projections of Social Security’s shortfall from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) suggests similar results. Nominal and real borrowing would be somewhat smaller – $520 trillion and $117 trillion, respectively. However, present value borrowing would be much larger at $38 trillion. Importantly, CBO’s baseline assumes benefits are paid beyond insolvency, though that would require a change in law.

General Revenue Funding Would Explode Debt-to-GDP

Funding Social Security with general fund transfers would increase debt by more than 130% of GDP by the end of the century, before accounting for dynamic effects. Assuming primary deficits, interest rates, and productivity growth remain stable after 2055 even as debt rises, that would mean nearly doubling projected debt levels. If higher debt continues to boost interest rates and slow economic growth, as expected, debt would grow much higher and the U.S. would likely enter a debt spiral, which could lead to a fiscal crisis.

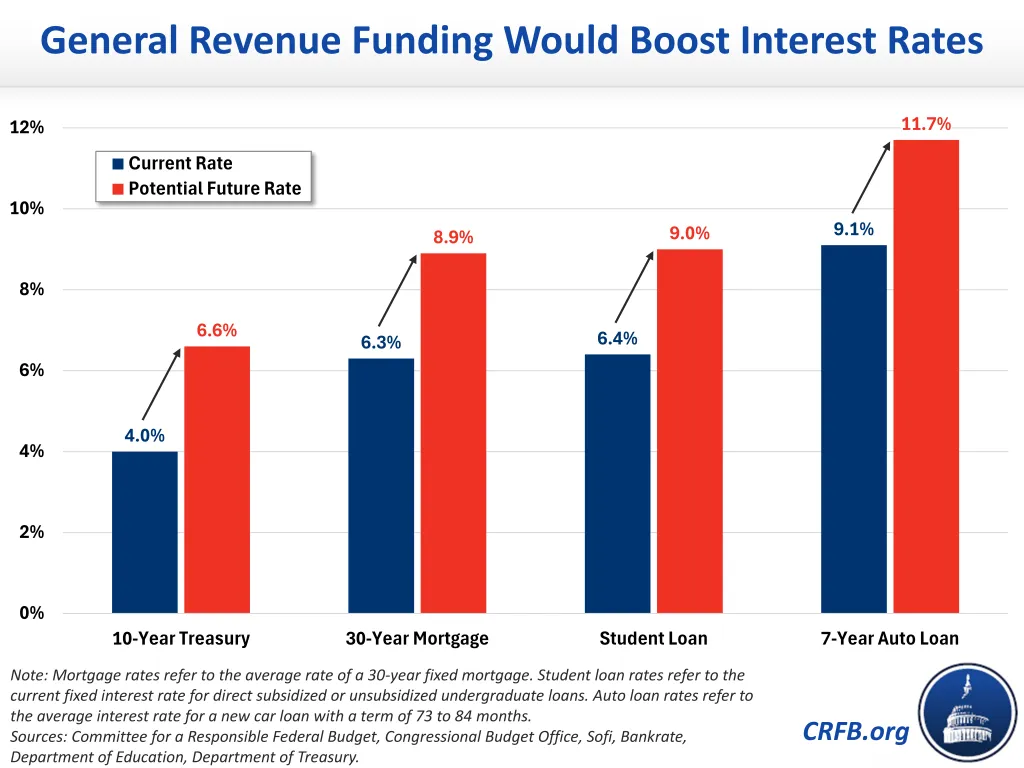

General Revenue Funding Would Push Up Interest Rates

One of the many negative consequences of high and rising debt is that it pushes up interest rates. CBO estimates that every additional 1% of GDP added to debt translates to a 2 basis point increase in interest rates. In boosting debt by 130% of GDP, borrowing to fund Social Security would therefore push up interest rates by an estimated 2.6 percentage points relative to maintaining the integrity of the trust fund. Some estimates suggest an even larger effect – perhaps as much as a 5 percentage point increase.

These higher interest rates would flow through to everything from Treasury bonds to mortgages to car loans. For example, if the current neutral rate on ten-year Treasury bonds is 4.0%, general funding for Social Security could push it up to 6.6%. If the average rate for a 30-year fixed rate mortgage is around 6.3%, general funding for Social Security could push it to near 9.0%.

General Revenue Funding Would End Social Security’s Current Structure

Since its inception 90 years ago, Social Security has operated as an internally funded program that is in many ways walled off from the rest of the federal budget. With some small exceptions, Social Security benefits have been financed with contributory payroll taxes and taxation of Social Security benefits. Social Security spending has not generally been allowed to exceed past and current dedicated revenue (plus interest), nor has the program’s spending been cut to finance other programs.

Funding Social Security’s shortfall with general revenues would end Social Security’s status as a contributory and self-funded program and make it more like any other government program.

While there is a reasonable case for changing Social Security’s treatment in the budget – assuming it is done in a fiscally responsible way – doing so would have fiscal, political, and economic consequences. Fiscally, it would remove the current restraints that require lawmakers to bring program costs and revenues in line. Politically, it would mean treating the program just like any other federal program, which means it would have to compete for the same resources as other programs and make it vulnerable to budgetary debate. Some have argued that it could also reduce public support for the program, which might no longer be thought of as an “earned benefit.” Economically, it could potentially reduce incentives to work, as beneficiaries would no longer feel as if their contributions to the program in the form of payroll taxes were linked to their future benefits.

General Revenue Funding Would Erode One of the Last Remaining Fiscal Rules

Many governments rely on fiscal rules – laws, regulations, or parliamentary rules – to limit the growth of deficits and debt and reassure creditors and investors about the stability of public finances and sovereign debt.

Although fiscal rules have been important historically in the United States, many have lost effectiveness over time. The statutory debt ceiling is regularly increased, often in combination with even more borrowing. Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) rules and laws – which used to effectively require new spending and tax cuts be fully offset – are frequently waived or circumvented. And discretionary spending caps – which limit appropriations – are now expired.

While trust funds represent some of the last remaining fiscal rules, they are also some of the strongest and most successful. They prevent lawmakers from indefinitely spending more than is collected in revenue or collecting less than is spent for major programs such as Social Security, Medicare Part A, and highways. Although even these trust fund constraints have sometimes been circumvented, the Social Security trust fund – which finances more than one-fifth of all federal spending – has generally been maintained. In 1977 and 1983, lawmakers acted to prevent trust fund insolvency through tax and benefit changes. Efforts to prevent future insolvency have been part of the political conversation since the early 1990s.

A general fund transfer would signify the end of the trust fund as a budget rule, and might signal to creditors that the United States is no longer willing to abide by fiscal constraints. Without this constraint, the federal debt is on a clearly unsustainable path. If credit rating agencies, investors, and others begin to believe there is little chance for course correction, interest rates could spike and – in the most extreme scenario – a fiscal crisis could ensue.

* * * * *

Social Security’s retirement program is only seven years from insolvency, at which point beneficiaries face a 24% across-the-board benefit cut. Lawmakers have numerous options to avoid these cuts, and our Social Security Reformer tool allows users to design their own plan.

General funding would technically avoid this immediate benefit cut, but only by shifting the burden to future generations – who will face higher interest rates, lower wages, and an out-of-control national debt. The United States is already deep in debt and should not go deeper just so policymakers can avoid taking action to rescue Social Security.

1 In addition to proposals that would explicitly borrow, transfer, or reallocate general revenues to fund Social Security, there are also proposals that would implicitly do so. For example, imposing an additional surtax on capital gains to fund Social Security would increase revenue into the program, but could also dramatically reduce income tax revenue by reducing capital gains realizations; at a high enough rate, this policy could reduce total capital gains revenue collection. Although some interactions with the general budget are inevitable, large interactions like this effectively represent a “backdoor” transfer of general revenues into Social Security.