SDPs Run Amuck - The Case of Medical Debt Forgiveness as a Pretext for High Payments

Medicaid provides health insurance to nearly 71 million people, and will cost the federal government over $650 billion this year – nearly double what it cost ten years ago.1 This cost growth is driven in part by the rapid growth in Medicaid supplemental payments. States sometimes cloak these large payments in various pretexts to justify excessively high amounts. But ultimately, the payments drive up Medicaid costs and undermine the financial sustainability of the program.

As one important example, the state of North Carolina has offered hospitals higher State Directed Payments (SDPs) in exchange for relieving patients’ medical debt through its new Healthcare Access and Stabilization Program (HASP).2 While reducing the financial burden of medical debt is a worthy policy goal, HASP appears to be mainly a pretext for expanding hospital payments. In this paper we explain:

- The amount of SDPs has been growing rapidly, driving up the federal cost of the Medicaid program nationwide.

- North Carolina’s SDP program, HASP, uses medical debt forgiveness as pre-text to boost hospital payments and increases federal dollars to hospital and state budgets.

- If HASP were actually using Medicaid funds to forgive debt, it would be a wasteful and inappropriate use of Medicaid dollars, spending at least $1.70 for every $1 of debt in the first three years of the program. In contrast, debt can be cancelled for pennies on the dollar. Furthermore, most of HASP’s benefits accrue to non-Medicaid recipients.

- HASP also cannot be justified as a reimbursement for hospitals’ uncompensated care, because hospitals already benefit from numerous other overlapping payments.

- The recently-enacted reconciliation law would limit HASP and other SDP schemes; these limits should be fully implemented.

Rather than using federal funds to finance excessive payments to hospitals and other providers, states interested in addressing medical debt should consider more cost-effective approaches, such as medical debt purchasing programs and should work to lower overall health care costs.

State Directed Payments Have Grown Rapidly Nationwide

Medicaid payments for medical services are often much lower than commercial insurance and even Medicare.3 However, states often make supplemental lump-sum payments to help ensure hospitals receive adequate funding for serving people in the Medicaid program or to achieve other goals, such as specific quality aims or to make up for care provided to people without insurance. States make several different forms of supplemental payments, including SDPs, a supplemental payment added to managed care payments.4

SDPs have grown significantly in recent years, from an estimated $25 billion in December 2020 to over $69 billion in February 2023.5 The SDPs approved as of August 2024 are projected to total $110 billion a year, a 60 percent increase from February 2023 and a 325 percent boost from 2020.6

SDPs have become increasingly popular in part because states can use provider taxes to collect additional federal Medicaid funds.7 States often simultaneously tax and boost payments to the same health care providers. In doing so, states receive federal matching funds so they can report higher costs without having to increase their net spending.8 Hospitals are amenable to paying the maximum provider taxes allowed by federal law because they are confident they will receive the same amount or more in return.

SDPs have also grown because The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized a rule in 2024 that set the cap on SDPs at the level of the average commercial rate (ACR) – which is far higher than what would typically be paid by either Medicaid or Medicare.9 One study estimated that the ACR for hospitals was more than two and a half times higher than Medicare rates in 2022, which in turn is typically higher than Medicaid rates.10 We previously estimated that this new regulation would cost $135 billion over a decade.

To curb these costs, the 2025 reconciliation law – OBBBA – imposes new limits on SDPs. The law restricts new SDPs to the amount Medicare pays in states that have adopted the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion and to 110 percent of Medicare in other states. For existing SDPs, these caps are phased in over time – with payment rates reduced 10 percentage points per year starting in 2028, until they reach the Medicare-based cap.11 The Congressional Budget Office estimates these limits will save $150 billion over nine years if allowed to take effect.12

The reconciliation law also restricts the use of provider taxes – banning new provider taxes, freezing some existing provider taxes, and gradually reducing some existing provider taxes.13 These changes should further reduce the incentive for states to offer overly-generous SDPs.14

North Carolina’s SDPs Used Medical Debt Relief as a Pretext

North Carolina’s HASP follows the national trend of paying hospitals SDPs at commercial rates, but does so with a twist: the state used medical debt forgiveness as a pretext to justify excessive payments to hospitals.15

HASP was pitched as a plan to provide medical debt relief to hospital patients. Hospitals voluntarily participate in the program, but to receive the maximum amount of SDPs at commercial rates, hospitals are required to:

- Work to forgive medical debt dating back to 2014 for patients with incomes at or below 350 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) or medical debt that is more than 5 percent of income.

- Discount medical bills by 50 to 100 percent for patients with incomes at or below 300 percent FPL.

- Proactively address patients’ eligibility for financial assistance (such as charity care), rather than rely on patients’ initiative to apply.

- Protect the personal credit of patients with incomes below 300 percent of FPL from legal issues related to medical debt by not selling medical debt to third-party collections agencies, and not reporting debt to credit agencies for other patients.

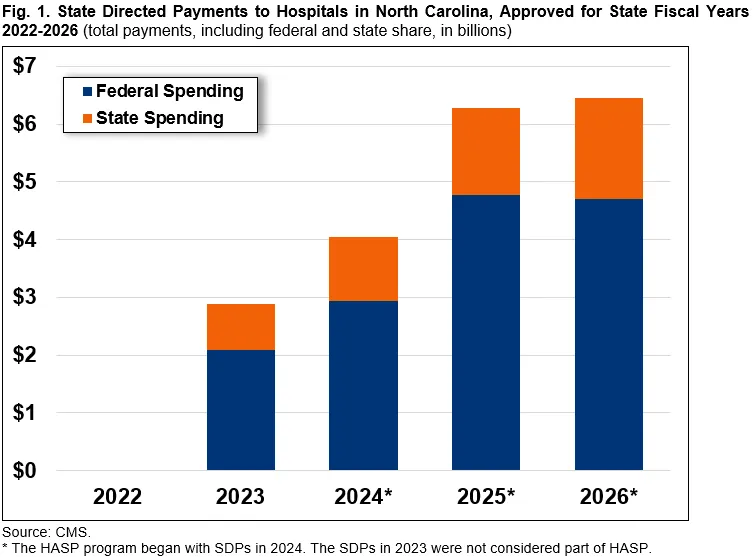

Beginning in the state's fiscal year 2024, CMS approved HASP to start paying SDPs that brought total payments to eligible hospitals up to the average commercial rate.16 (Prior to that time, in 2023, the new non-HASP SDPs had totaled $3 billion – 14 percent of North Carolina’s total Medicaid spending in that year.17 ) Since then, SDP totals have more than doubled to more than $6 billion. 18

Prior to the SDP increases, the state’s managed care plans’ “base rates” were set at the same rate that Medicare pays, which CMS calculates to cover the cost of care for Medicare patients. The SDPs up to the ACR more than doubled the base rates, raising questions about what hospitals were doing with the extra Medicaid funds.19

According to a tool created by National Association of State Health Policy (NASHP), North Carolina hospitals’ “break-even point”—the payment rate at which hospitals cover their costs—was roughly 145 percent of Medicare in 2023.20 In state fiscal year 2023, SDPs to hospitals totaled an average of roughly 210 percent, well above break even. With 2024 SDPs authorized up to $4 billion and 2025 and 2026 authorized over $6 billion each year, the percentage of Medicare rates will rise much higher.21

Because provider taxes fuel the SDPs, the taxes should be netted out of the gross payment amounts. After taking out the provider taxes, hospitals in North Carolina still received between approximately 160 to 190 percent of Medicare rates, well above the NASHP “break even” point of 145 percent of Medicare in 2023.

SDPs are a Costly, Inefficient, and Inappropriate Way to Provide Medical Debt Relief

Medical debt is an important problem in North Carolina and nationwide, but if the goal of HASP is to forgive medical debt, it does so incredibly inefficiently – costing tens of times as much as is necessary.

The governor’s office estimated that HASP will result in hospitals cancelling about $4 billion worth of medical debt. The payments themselves cost over $16.5 billion in the first three years of HASP, of which $7 billion was conditioned on medical debt cancellation.22 That means, in the first three years, hospitals are being paid $1.70 for every $1 of debt relief.

By comparison, most medical debt relief programs nationwide cancel medical debt for pennies on the dollar. States and cities nationwide have been purchasing medical debt from collection agencies to cancel debt for individuals. For example, New Jersey recently announced that it used $5.8 million to purchase and forgive approximately $1 billion in medical debt.23 And in North Carolina itself, the state has partnered with the organization Undue Medical Debt, which uses donations to buy medical debt at 1 percent of the cost of the debt.24

Furthermore, HASP’s relief efforts generally benefit people who are not enrolled in Medicaid because Medicaid already protects enrollees from medical debt. Medicaid beneficiaries rarely accrue medical debt while insured by the program because they are typically not charged with significant cost sharing, and cannot be charged the “balance” for a particular health care service (a process referred to as “balance-billing”). As noted above, debt relief is targeted to patients with incomes below 350 percent of the FPL (up to $109,000 for a family of four in 2024).25 This level is significantly higher than the income level for Medicaid beneficiaries in North Carolina.26

Instead of Medicaid enrollees, the hospital debt relief measures largely benefit people not enrolled in Medicaid. Using Medicaid funds to support those with too much income to qualify for the program is an improper use of those funds that can ultimately strain the program’s finances.

In reality, HASP does not appear to be mainly about medical debt relief, and in fact does not use Medicaid funds to directly pay off debt. At best, the debt relief goal is secondary. More likely, it is a pretext to dramatically increase hospital payments. And because North Carolina’s SDPs were approved with a blended FMAP rates between 73 and 76 percent (depending on the year), the federal government must bear three quarters of the costs.27 This also makes using provider taxes to generate SDPs particularly attractive to the state.28

SDPs Are Unnecessary to Support Hospital Uncompensated Care Costs

Medical debt for individuals is uncompensated care for hospitals. In other words, medical debt arises when patients do not fully remit their copays or the balance of their claims for care they received. However, SDPs are not necessary to fill this gap, as hospitals already benefit from multiple funding streams on top of the usual insurance reimbursements that help ensure that they are paid to provide care. This fact further undermines states’ justification for SDPs at ACR.

The existing sources of support include:

- DSH Payments – Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are designed to help hospitals address revenue shortfalls due to caring for uninsured individuals and others.29 In Fiscal Year (FY) 2022, North Carolina hospitals received $434 million in Medicaid DSH payments, although they no longer qualified for DSH once the SDP payments began in 2023.30 Some hospitals likely received additional funds from Medicare DSH and Medicare and uncompensated care payments.31

- Upper Payment Limit (UPL) payments – States provide non-DSH supplemental payments called “UPL payments” to hospitals on top of fee-for-service payments that are below the rate Medicare would pay for the same services.32 In federal fiscal year 2023, North Carolina hospitals received $420 million in UPL payments.33

- 340B Drug Discounts – The 340B Drug Pricing Program requires drug manufacturers to sell outpatient drugs at discounted prices to covered entities (including certain hospitals). In addition to realizing savings through 340B price discounts, hospitals can generate revenue when purchasing 340B drugs for eligible patients whose insurance reimbursement exceeds the 340B price paid for the drugs. 41 out of 111 hospitals in North Carolina participate in the 340B program.34

- Medicare Bad Debt Reimbursements – Medicare reimburses hospitals for 65 percent of bad debt accrued from patients who do not pay all of the cost-sharing they owe. The state was careful to design HASP so as not to interfere with bad debt payments from past medical encounters.35

- Tax Benefits – From 2019 to 2020, the 85 percent of hospitals in North Carolina that are nonprofit received more than $1.8 billion in federal, state, and local tax breaks.36 To justify the tax exemption, hospitals commonly provide “charity care,” or free services to those who cannot afford to pay. Though as we previously explained, so-called “non-profit hospitals” often deliver less charitable care than for profit hospitals.

These funding streams provide billions of dollars to hospitals and obviate the need for further relief from uncompensated care. The SDPs obtained by North Carolina hospitals exceed what is necessary to compensate them for caring for patients enrolled in Medicaid.

New Limits on SDPs Should Be Allowed to Take Effect

The recently-enacted reconciliation law, also known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), includes important new limits on both SDPs and provider taxes.37 In particular, states will be required to set SDP rates based on Medicare rates, with a phase-down for existing SDPs beginning in 2028.

However, both political parties have already begun to exert significant pressure to reverse these limits.38 Doing so would not only preserve costly schemes in North Carolina and elsewhere, but give license for additional states to follow suit.

North Carolina is one of many states making payments as high as the average commercial rate to hospitals and other Medicaid providers nationwide. While North Carolina’s justification may be among the flimsiest, other states have used other justifications as pretenses to boost hospital payments and increase federal funding.

Reducing medical debt may be a desirable policy goal, but using Medicaid funds to cancel debt for non-Medicaid patients – and doing so at many times the necessary cost – undermines the sustainability of the program. In practice, there is little justification to support medical debt relief through SDPs. Nor is the policy justified as a reimbursement to hospitals, who already benefit from DSH payments and many other overlapping funding streams.

Congress and the Administration should ensure that new limits on SDPs are implemented as intended, and that new schemes do not arise to replace them. States interested in relieving medical debt could establish and fund medical debt purchase programs or find other cost-effective ways to lower medical debt – and should also focus on reducing the high health care costs that lead to medical debt in the first place – rather than extracting federal Medicaid dollars.

With the national debt approaching historic levels, state governments and the federal government must both practice good fiscal stewardship when it comes to the Medicaid program.

1 Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035,” January 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2025-01/60870-Outlook-2025.pdf, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), “April 2025 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights (accessed August 27, 2025).

2 North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS), “CMS Approves North Carolina’s Medical Debt Relief Incentive Program,” July 29, 2024, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2024/07/29/cms-approves-north-carolinas-medical-debt-relief-incentive-program.

3 Whaley et al., “Prices Paid to Hospitals by Private Health Plans,” RAND, 2024, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1144-2-v2/RAND_RRA1144-2-v2.pdf. See also, Mann, Cindy and Adam Strier, “How Differences in Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial Health Insurance Payment Rates Impact Access, Health Equity, and Cost,” Commonwealth Fund,” August 17, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/how-differences-medicaid-medicare-and-commercial-health-insurance-payment-rates-impact.

4 Other forms of supplemental payments include: disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments; non-DSH supplemental payments; supplemental payments resulting from demonstration waivers; and pass-through payments.

5 Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC), “Directed Payments in Medicaid Managed Care,” October 2024, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Directed-Payments-in-Medicaid-Managed-Care.pdf.

6 Id.

7 Congressional Research Service, “Medicaid Provider Taxes,” December 30, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RS22843.

8 Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), “Medicaid Provider Taxes Inflate Federal Matching Funds,” September 28, 2023, https://www.crfb.org/papers/medicaid-provider-taxes-inflate-federal-matching-funds.

9 Federal Register, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Program; Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Manage Care Access, Finance, and Quality,” 42 CFR Parts 430, 438, and 457, May 10, 2024, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/05/10/2024-08085/medicaid-program-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-managed-care-access-finance.

10 Whaley, et al., “Prices Paid to Hospitals by Private Health Plans,” RAND, 2024, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1144-2-v2/RAND_RRA1144-2-v2.pdf. Traditional Medicare sets rates for hospitals that aim to ensure access to care for beneficiaries, using a variety of data sources, including hospitals’ reports on the costs incurred in caring for Medicare beneficiaries. Hospitals have argued that providers must set commercial rates to levels well above Medicare and Medicaid to compensate for any shortfall below cost, although others have disputed that contention. CBO reported that, contrary to popular belief, the cost difference is not due to commercial insurers offsetting the low prices paid by government programs. See: CBO, “The Prices that Commercial Health Insurance and Medicare Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services,” January 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-01/57422-medical-prices.pdf.

11 See Sec. 71116: One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, 119th Congress, 2025 https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1.

12 CBO, “Estimated Budgetary Effects of an Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Relative to CBO‘s January 2025 Baseline,“ June 29, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61534.

13 See Sec. 71115: One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, 119th Congress, 2025 https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1.

14 OBBBA will limit certain provider taxes starting in federal fiscal year 2028. CBO estimated that this policy change will save $190 billion in federal spending. We estimate that completely removing provider tax schemes could save up to $720 billion over ten years, and limiting provider taxes could save between $55 billion and $285 billion. See: CRFB, “Hundreds of Billions in Medicaid Savings from Financing Schemes,” February 20, 2025, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/hundreds-billions-medicaid-savings-financing-schemes and CRFB, “Medicaid Savings Options,” December 12, 2024, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/medicaid-savings-options.

15 MACPAC, “Directed Payments in Medicaid Managed Care,” October 2024, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Directed-Payments-in-Medicaid-Managed-Care.pdf.

16 See page 3, CMS, ”North Carolina State Directed Payment Approval Package, control name NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Renewal_20230701-20240630,” July 26, 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Renewal_20230701-20240630.pdf.

17 See page 3, CMS, ”North Carolina State Directed Payment Approval Package, control name NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Amend2_20220701-20230630,” March 5, 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Amend2_20220701-20230630.pdf. See also: MACPAC, “Medicaid Spending by State, Category, and Source of Funds, FY 2023,” 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/EXHIBIT-16.-Medicaid-Spending-by-State-Category-and-Source-of-Funds-FY-2023.pdf. For comparison, the state’s total amount of federal and state Medicaid spending in federal fiscal year 2023 was $20.4 billion.

18 See page 3: CMS, ”North Carolina State Directed Payment Approval Package, control name NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Renewal_20250701-20260630,“ Jan. 17, 2025, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH….

19 CMS, ”North Carolina State Directed Payment Approval Package, control nameNC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Amend2_20220701-20230630,” March 5, 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed- care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Amend2_20220701-20230630.pdf. Data is as of July 1, 2022, the most recent date for which information is available.

20 NASHP, “Hospital Cost Tool,” February 7, 2025, https://tool.nashp.org.

21 CMS first approved base payments plus SDPs of $2.6 billion, before later allowing the SDPs to be increased to $2.9 billion. CMS, “Approval of amendment NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI. BHO_ Amend_20220701-20230630 to previous state directed payment approval,” December 12, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Amend_20220701-20230630.pdf.

22 NCDHHS, ”Hospital Payment Program and Medical Debt Relief Initiative Approved for Another Year,” February 5, 2025, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2025/02/05/hospital-payment-program-and-medical-debt-relief-initiative-approved-another-year.

23 State of New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, “Governor Murphy Partners with Undue Medical Debt and RWJBarnabas Health on Fourth Round of Medical Debt Relief, Eliminating $927 Million in Debt for 629,000 New Jerseyans,” April 21, 2025, https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562025/20250421b.shtml.

24 Undue Medical Debt, “Solutions to Buy Medical Debt,” https://unduemedicaldebt.org/solutions-to-buy-medical-debt/. NCDHHS, ”Hospital Payment Program and Medical Debt Relief Initiative Approved for Another Year,” February 5, 2025, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2025/02/05/hospital-payment-program-and-medical-debt-relief-initiative-approved-another-year.

25 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS, ”2024 Poverty Guidelines Computations,” January 2024, https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2024-poverty-guidelines-computations.

26 Like most states, North Carolina sets eligibility levels for different groups of beneficiaries at different income levels: 138 percent of FPL for expansion enrollees; 211 percent for children; 196 percent for pregnant women; and 100 percent for people with disabilities. See, MACPAC, ”Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility,” https://www.macpac.gov/macstats/eligibility/.

27 CMS approved a blended FMAP that combines the expansion population rate of 90%, a bonus of 5 percentage points due to the American Rescue Plan’s temporary FMAP increase for newly-expanding states, and the non-expansion population’s rate of 65%. For example, see page 2, responses to question 4: CMS, “Approved State Directed Payment Preprints,” July 26, 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/downloads/NC_Fee_IPH.OPH.BHI.BHO_Renewal_20240701-20250630.pdf. See also Fiscal Research Division, A Staff Agency of the North Carolina General Assembly, “State Savings from Adding NC Health Works Medicaid Coverage,” February 6, 2024, https://webservices.ncleg.gov/ViewDocSiteFile/83443#:~:text=Incentive%3A%20For%208%20fiscal%20quarters,non%2Dexpansion)%20Medicaid%20program.&text=NC's%20current%20base%20FMAP%20is,incentive%20increases%20this%20to%2070.91%25.

28 In fact, North Carolina did not use any state general funds to finance the state’s share of the SDPs. Rather, the state used only provider taxes. North Carolina Medicaid, Annual Report for State Fiscal Year 2024, https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/medicaid-annual-report-sfy-2024-english/download?attachment, (accessed Sept. 9, 2025).

29 CRFB, “Reform Needed for Medicaid DSH,” December 5, 2024, https://www.crfb.org/papers/reform-needed-medicaid-dsh. As we have reported previously, since hospitals have many other ways of paying for uncompensated care, Congress should allow DSH payments to be reduced as written in current law.

30 MACPAC, “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals, Issue Brief,” April 2024, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf.

31 Nationwide in FY25, Medicare DSH payments were projected to be approximately $16 billion nationwide, and Medicare uncompensated care payments totaled about $6 billion in 2025. See: Federal Register, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicare Program; Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems for Acute Care Hospitals (IPPS) and the Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System and Policy Changes and Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Rates; Changes to the FY 2025 IPPS Rates Due to Court Decision; Requirements for Quality Programs; and Other Policy Changes; Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability: Electronic Prescribing, Real-Time Prescription Benefit and Electronic Prior Authorization,” 42 CFR Parts 412, 495, and 512, August 5, 2025, https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2025-14681.pdf.

32 For this reason, the payments are often referred to as “UPL payments.”

33 MACPAC, “MACStats : Medicaid and CHIP Data Book, Exhibit 24: Medicaid Supplemental Payments to Hospital Providers by State, FY 2023,” December 2024, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/EXHIBIT-24.-Medicaid-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospital-Providers-by-State-FY-2023.pdf.

34 North Carolina State Health Plan for Teachers and State Employees Health Care Policy, “Overcharged: State Employees, Cancer Drugs, and the 340B Drug Pricing Program,” accessed Aug. 27, 2025, https://www.shpnc.gov/documents/overcharged-state-employees-cancer-drugs-and-340b-drug-price-program/download?attachment.

35 The state also noted that going forward, hospitals that receive HASP payments will not be eligible for Medicare Bad Dept Reimbursements, but that loss is a small share of hospitals’ revenue and is far outweighed by HASP payments. See page 9: NCDHHS, ”North Carolina Toolkit for Other States on Medical Debt Initiative,” December 2, 2024, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/medical-debt-toolkit/download?attachment.

36 North Carolina State Health Plan and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, ”North Carolina Hospitals: Charity Care Case Report,“ Oct. 27, 2021, https://www.shpnc.gov/documents/files/north-carolina-hospitals-charity-care-case-report/open.

37 See Sec. 71116: One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, 119th Congress, 2025 https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1.

38 See: Protecting Health Care and Lowering Costs Act, S.2556, 119th Congress, 2025, https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Protecting%20Health%20Care%20and%20Lowering%20Costs%20Act.pdf. See also: Protect Medicaid and Rural Hospitals Act, S.2279, 119th Congress, 2025, https://www.hawley.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Hawley-Protect-Medicaid-and-Rural-Hospitals-Act.pdf.