Principles for Social Security Reform

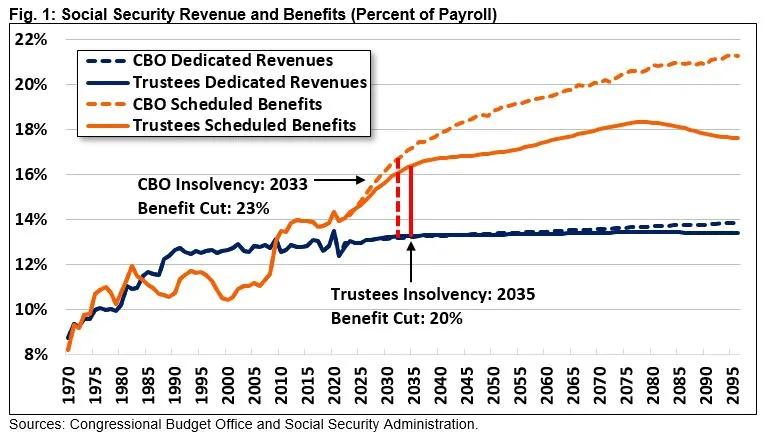

Social Security will be insolvent in as little as a decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the combined trust funds’ reserves will be depleted by 2033. The Social Security Trustees have projected the trust funds will run out in 2035. At that point, the program will only be allowed to pay 75 to 80 percent of benefits under the law, meaning all beneficiaries will face a deep across-the-board benefit cut.

Lawmakers should reform Social Security to avoid this indiscriminate cut, while protecting the financial integrity of the Social Security program and the rest of the federal budget. A responsible reform package should abide by these five principles:

- Strengthen Social Security as soon as possible to extend the life of the trust funds. Begin to phase in benefit and/or revenue adjustments as quickly as possible to strengthen Social Security’s finances. The sooner these changes are made, the less painful they will be – already we have waited to the point that many participants will be affected when they didn’t have to be.

- Support the most vulnerable, who depend on the program. Enact reforms that avoid the abrupt across-the-board benefit cut projected under current law, while protecting benefits for those who rely on the program most and focusing adjustments on those who can best afford them.

- Promote stronger economic growth and productive aging. Remove work and savings disincentives in the current program, while enacting reforms to support older workers and workers with disabilities, enhance retirement flexibility, encourage savings, and promote economic growth.

- Rely on honest accounting, avoiding gimmicks and cost-shifting. Improve solvency by reducing costs and/or increasing revenue collection, not by shifting costs outside of Social Security, supporting further borrowing, pushing costs into the future, or relying on arbitrary expirations.

- Don’t criticize others’ solutions, especially if you don’t have your own. Reject partisan and special interest demagoguing of Social Security solutions, understanding that any final solution is likely to require compromise. Present alternatives rather than lobbing criticisms. Promising not to do anything is the most irresponsible promise one can make when it comes to Social Security.

Strengthen Social Security Soon to Extend the Life of the Trust Funds

CBO estimates that Social Security’s theoretically combined trust funds are only a decade from running out of reserves, while the Social Security Trustees estimate 12 years until depletion. Assuming the Trustees’ 2035 insolvency date, the program will no longer be able to pay full benefits when today’s 55-year-olds reach the normal retirement age and today’s youngest retirees turn 74. At that point, benefits would automatically be cut by 20 to 25 percent across the board.

Any Social Security reform plan should, first and foremost, extend the solvency of the program to avoid the automatic cuts scheduled under current law. Comprehensive reform should achieve sustainable solvency to ensure benefits can be paid in full for the next 75 years and beyond. According to the Trustees, this will require adjustments equal to 3.4 percent of taxable payroll – which is about 25 percent of revenue or 20 percent of benefits – over the next 75 years. By the 75th year, necessary adjustments will grow to 4.3 percent of taxable payroll, which is about a third of revenue or one-quarter of benefits.1

Lawmakers should act as soon as possible to spread the costs over more cohorts and give workers time to plan and adjust. The longer they delay action, the larger the cuts or tax hikes that will be needed, the less opportunity there will be to phase in, and the fewer options will be available.

CBO estimates that adjustments will need to be equal to 4.9 percent of taxable payroll – 40 percent of revenue or 26 percent of benefits over the next 75 years. By 2096, the necessary adjustments will total 7.4 percent of taxable payroll, equal to 53 percent of revenue or 35 percent of benefits.

Lawmakers could also choose to pursue incremental reforms designed to extend the life of the trust fund and shrink but not eliminate the gap between spending and revenue. This would be a huge step in the right direction. However, lawmakers should avoid any significant benefit enhancements or revenue reductions outside of a comprehensive solvency package.

Support the Most Vulnerable, Who Depend on the Program

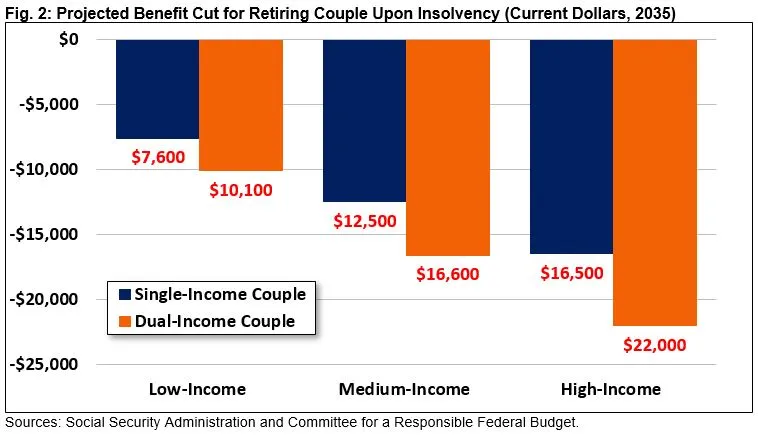

The sharp across-the-board benefit reduction slated to occur upon insolvency would be harmful to most beneficiaries – representing an immediate $12,500 to $16,600 cut in annual benefits for a typical couple retiring in 2035. The cut could be devastating for those who rely on the program most, including those with low lifetime earnings and little savings, widow(er)s, workers and retirees with disabilities, and the very old.

Social Security reform should extend the solvency of the program to prevent these deep cuts, while ensuring adequate benefits for those who rely on the program most. Revenue and benefit adjustments to improve solvency should be targeted toward those who can best afford them, including those with high current or lifetime incomes.

Comprehensive reform could also enhance benefits for the most vulnerable through a more progressive benefit formula, a stronger minimum benefit, or other changes to strengthen retirement security and support those who rely on the program.

Promote Stronger Economic Growth and Productive Aging

Social Security is inexorably linked to the economy. Social Security is the single largest federal program and the largest source of retirement income for most households, while its payroll tax is the largest tax paid by most workers. The design of the program affects the size of the national debt; incentives to work, save, and invest; and the supply of labor and capital in the economy.

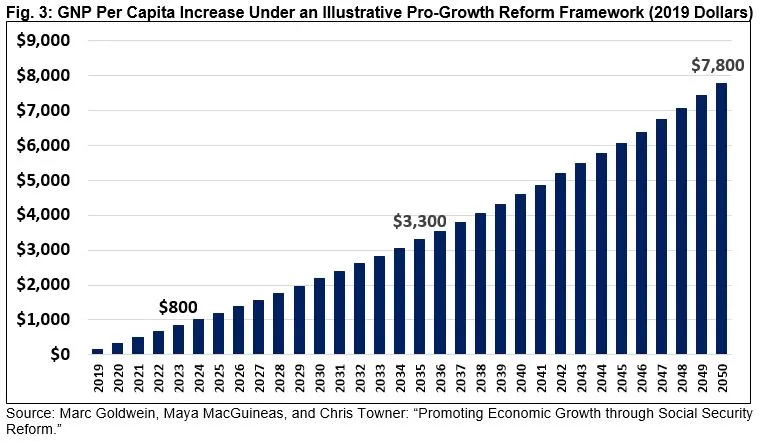

As the population ages, forecasters project a permanent slowdown in economic growth. Thoughtful Social Security reform should help to mitigate these effects by boosting household incomes and national output.

Reform can support stronger growth by reducing unified budget deficits, fixing provisions in the current program that discourage work and savings, supporting workers with disabilities, and promoting productive aging among those who would prefer to remain in the labor force or consider a more flexible arrangement in place of full retirement.

A significant body of literature has shown that, for many workers, delaying retirement increases wealth and income, improves mental and physical health, encourages positive social interactions and the maintenance of social networks, and brings about widespread societal gains.2

In Promoting Economic Growth through Social Security Reform, Goldwein, MacGuineas, and Towner estimated their pro-growth Social Security reform framework could accelerate the growth rate by roughly 25 basis points per year – increasing GNP per capita by nearly $8,000 by 2050.3

Rely on Honest Accounting, Avoiding Gimmicks and Cost-Shifting

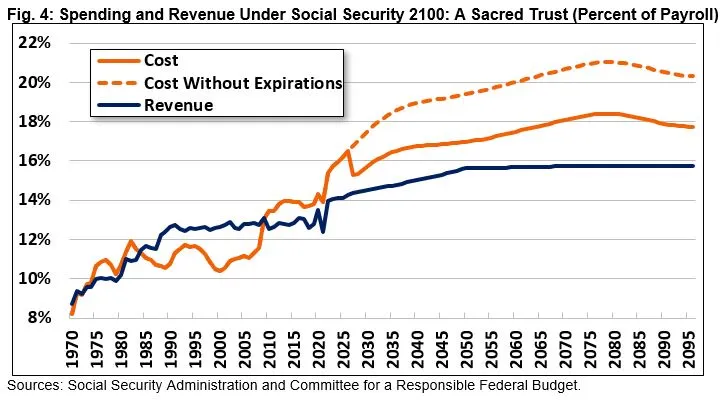

Permanent, thoughtful, and long-term fixes to Social Security can help avoid insolvency, strengthen retirement security, promote economic growth, and improve the fiscal outlook. A responsible reform plan should rely on these types of fixes, rather than gimmicks, games, and intragovernmental cost-shifting.

For example, a reform plan should avoid temporary benefit expansions or tax reductions with arbitrary sunsets, such as those in Social Security 2100: A Sacred Trust. That legislation would close half the solvency gap on paper by combining a higher taxable maximum with numerous benefit expansions that expire after just five years. If those benefit expansions were continued, the legislation would actually worsen solvency.

Social Security reform should also avoid policies that improve Social Security’s finances mainly by worsening the finances of the rest of the government. It would be irresponsible to allow the trust funds to transfer or borrow from other parts of government on a sustained basis, to dedicate already-existing revenue sources to the trust fund without offsets, or to rely on solvency-improving policies that result in major new costs or revenue losses outside of Social Security.4

Solvency improvements should come from policies that bring revenue and costs more closely in line, not from gimmicks, games, and manipulations.

Don’t Criticize Others’ Solutions, Especially if You Don’t Have Your Own

Social Security has long been called the third rail of American politics. Over the years, special interest groups and politicians in both parties have sought to demagogue those trying to fix the program in order to raise money or achieve temporary political advantage.

There is no one right or best way to make Social Security solvent, but failure to act will lead to the worst way – an automatic 20 to 25 percent across-the-board cut at the time of insolvency.

Restoring the program’s solvency will require healthy debate with all options on the table. Republicans and Democrats can’t approach the issue as two separate teams. Rather than attacking opponents on proposals that try to address the problem, policymakers should be focused on putting forward their own specific plans to secure the program and engaging in conversations across the aisle, presenting alternatives.

Ignoring the problem and kicking hard decisions further down the road will only make solving the deteriorating fiscal situation more difficult. For example, in 2010 the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles plan would have restored solvency to the Social Security program by phasing in changes over 40 years, by 2050. If a similar plan were enacted today, it would need to be phased in over five to 10 years to achieve the same results.

Rather than ignoring the problem, policymakers should ignore special interest groups who are more interested in raising money than identifying solutions. This includes groups who demand politicians “take a stand” or “have a plan,” and then attack those plans when they come to light.

While tough trade-offs are inevitable, there are many options available to policymakers. Policymakers could also create a commission or rescue committee to help address the issue. Whichever route is taken, action should be immediate and swift to avoid the cost of waiting, and compromise should be expected.

1 CBO estimates that adjustments will need to be equal to 4.9 percent of taxable payroll – 35 percent of revenue or 26 percent of benefits over the next 75 years. By 2096, the necessary adjustments will total 7.4 percent of taxable payroll, equal to 53 percent of revenue or 35 percent of benefits.

2 For a recent comprehensive assessment of the benefits of encouraging older people to work longer, see National Academy of Medicine. 2022. Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26144; see also Dhaval Dave, R. Inas Rashad, and Jasmina Spasojevic, “The Effects of Retirement on Physical and Mental Health Outcomes,” Southern Economic Journal, Southern Economic Association, vol. 75(2), January 2008, pages 497-523; Alice Zulkarnain and Matthew S. Rutledge, “How Does Delayed Retirement Affect Mortality and Health?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper #2018-11 (October 2018), http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/wp_2018-11.pdf; and Elenora Patacchini and Gary V. Engelhardt, “Work, Retirement, and Social Networks at Older Ages,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Working Paper #2016-15 (November 2016), http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/wp_2016-15.pdf.

3 Marc Goldwein, Maya MacGuineas, and Chris Towner, “Promoting Economic Growth through Social Security Reform,” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, September 19, 2019, https://www.crfb.org/papers/promoting-economic-growth-through-social-security-reform.

4 Although these types of policies are irresponsible as a general matter, there are some circumstances in which they may be acceptable. For example, it may be reasonable for a comprehensive solvency plan to rely on a very short-term reallocation or borrowing from another trust fund to manage a transition. Additionally, some interactions between Social Security and other parts of the budget are inevitable and should not be reason to dismiss a plan that is responsible overall. However, borrowing should not be used to fund benefits or other costs for a significant period of time, and an overall plan should aim to have minimal – or improving – effects on the rest of the budget.