Analysis of the 2022 Social Security Trustees' Report

Today, the Social Security and Medicare Trustees released their annual reports on the long-term financial state of the Social Security and Medicare programs. The latest Social Security projections show the program is quickly headed toward insolvency and highlight the need for trust fund solutions sooner rather than later to prevent across-the-board benefit cuts or abrupt changes to tax or benefit levels. The Social Security Trustees found:

- Social Security is only 13 years from insolvency. Social Security cannot currently guarantee full benefits to current retirees. The Trustees project the Social Security Old-Age & Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund will deplete its reserves by 2034. And though the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund is in strong financial shape, the theoretically combined trust funds will exhaust their reserves by 2035, when today’s 54-year-olds reach the full retirement age and today’s youngest retirees turn 75. Upon insolvency, all beneficiaries will face a 20 percent across-the-board benefit cut.

- Social Security faces large and rising imbalances. According to the Trustees, Social Security will run cash deficits of nearly $2.5 trillion over the next decade, the equivalent of 2.1 percent of taxable payroll or 0.8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Annual deficits will grow to 3.4 percent of payroll (1.2 percent of GDP) by 2040 and total 4.3 percent of payroll (1.4 percent of GDP) by 2096. Social Security’s 75-year actuarial imbalance totals 3.4 percent of payroll, which is 1.2 percent of GDP or over $20 trillion in present value terms.

- Social Security’s finances have improved slightly from last year, but remain perilous. Social Security’s finances are slightly better than projected in the 2021 report – insolvency is projected to occur a year later, and the 75-year actuarial shortfall is 0.12 percentage points smaller. However, the 75-year shortfall is 1.5 percentage points larger than it was projected to be back in 2010.

- Time is running out to save Social Security. Policymakers have only a few years left to restore solvency to the program, and the longer they wait, the larger and more costly the necessary adjustments will be. Acting now will allow more policy options to be on the table, let policymakers phase in changes more gradually, and provide more time for people to adjust their work and savings habits if necessary.

Given the short timeline to address the looming insolvency of Social Security – and Medicare Hospital Insurance (addressed in a companion paper) – policymakers should take any opportunity to enact trust fund solutions.

Social Security is Only 13 Years from Insolvency

The Social Security program is only 13 years from insolvency, and action must be taken soon to prevent an across-the-board benefit cut for many current and future beneficiaries.

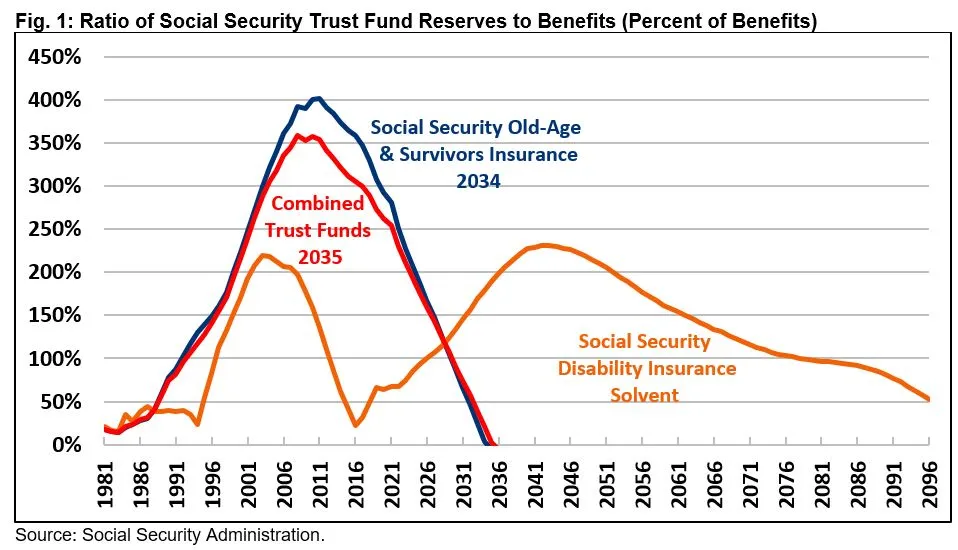

The Trustees project the Social Security OASI trust fund will deplete its reserves by 2034; the SSDI trust fund is in much stronger shape and will not be exhausted during the 75-year projection window for the first time since the 1983 Trustees’ report. On a theoretically combined basis – assuming revenue is reallocated between the trust funds in the years between OASI and SSDI insolvency – Social Security will become insolvent by 2035.

Upon insolvency, all retirees regardless of age, income, or need will face a 20 percent across-the-board benefit cut, which will grow to 26 percent by the end of the projection window.

The year 2035 is only 13 years away. That means the Social Security trust funds are on course to run out of reserves when today’s 54-year-olds reach the normal retirement age and when today’s youngest retirees turn 75. For perspective, the average new retiree will live to age 85, meaning Social Security cannot guarantee full benefits for many current beneficiaries, let alone future ones.

Meanwhile, the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund is only six years from insolvency and will exhaust its reserves in 2028 according to the Medicare Trustees. The Trustees’ findings are similar to recent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which found the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund will be insolvent by 2030 and suggest the Social Security trust funds will be exhausted by 2033.

Social Security Faces a Large and Growing Shortfall

The Trustees project Social Security will run chronic deficits. They estimate the program will run a cash-flow deficit of $112 billion this year – which is 1.3 percent of taxable payroll or 0.5 percent of GDP. Social Security will run nearly $2.5 trillion of cumulative deficits over the next decade.

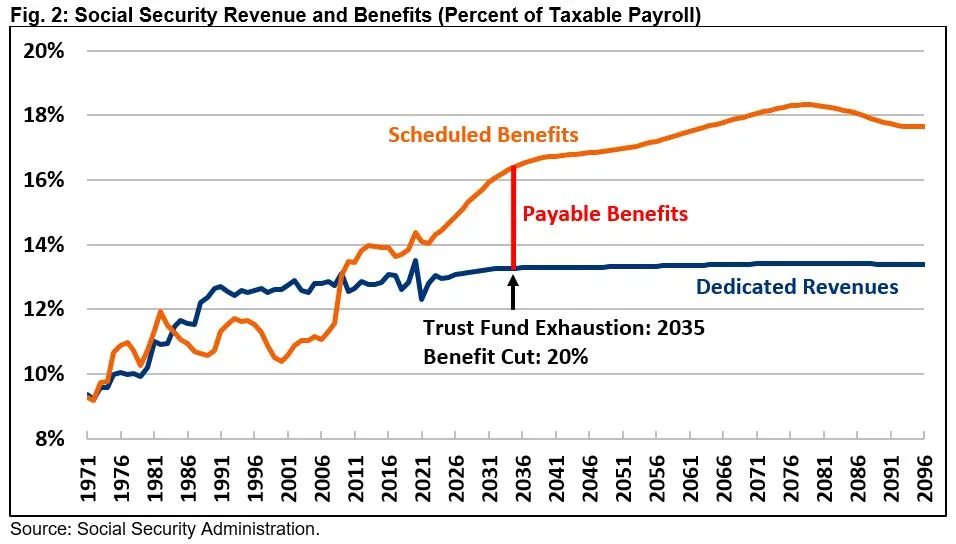

Over the long term, the Trustees project Social Security’s cash shortfall (assuming full benefits are paid) will grow to 2.8 percent of taxable payroll (1.0 percent of GDP) by 2032, to 3.5 percent of payroll (1.2 percent of GDP) by 2042, and to a high of 4.9 percent of payroll (1.7 percent of GDP) by 2079. Costs will then decline to 4.3 percent of payroll (1.4 percent of GDP) by 2096.

Social Security’s rising long-term shortfall is largely the result of rising costs, mainly due to the aging of the population. Total Social Security costs have already risen from 10.9 percent of taxable payroll in 2002 to 14.1 percent in 2022 and are projected to rise further, to 16.1 percent of payroll by 2032, to 16.8 percent by 2042, and to 17.6 percent by 2096. Revenue will fail to keep up with growing costs, rising only modestly from 12.8 percent of payroll today to 13.4 percent by 2096.

Typically, the Trustees measure Social Security’s financial imbalance over 75 years. They find the program faces an actuarial shortfall of 3.42 percent of taxable payroll, which is 1.2 percent of GDP or over $20 trillion in present value terms. A plan to restore sustainable solvency over the next 75 years would require the equivalent of increasing payroll taxes immediately by 26 percent, reducing spending by 20 percent for all current and future beneficiaries, or some combination. Actual reforms could be better targeted, rather than across-the-board, and phased in gradually.

Social Security’s Finances Are Slightly Improved, but Remain Perilous

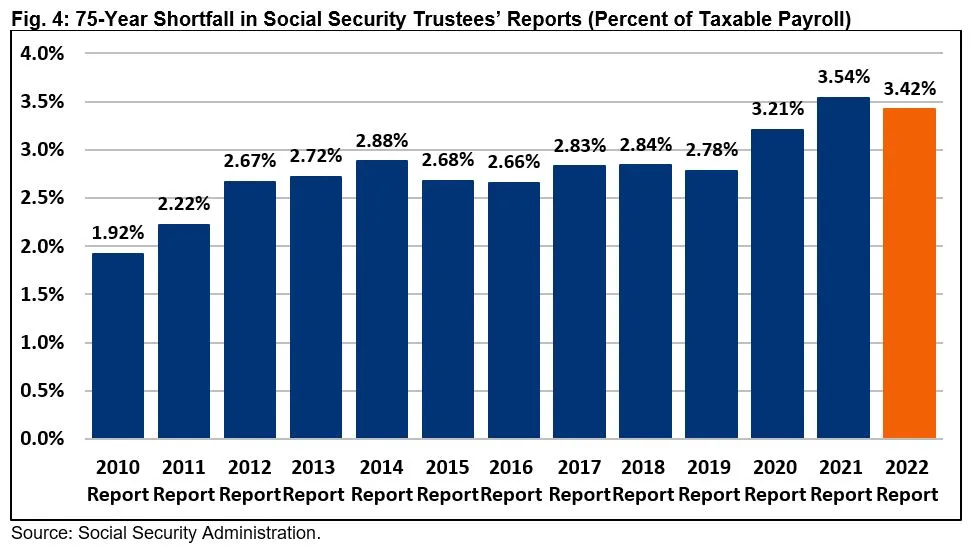

Social Security’s finances are slightly improved relative to last year but have worsened substantially over the last dozen years. The last Social Security Trustees report, released in August 2021, estimated an insolvency date of 2034 and a 75-year actuarial imbalance of 3.54 percent of taxable payroll. The Trustees now project Social Security will remain solvent until 2035, one year later than last year’s estimate, and faces a 75-year shortfall of 3.42 percent of payroll.

Relative to last year, economic changes improved the 75-year shortfall by 0.13 percentage points of payroll. Specifically, increases in real interest rates through 2024 improved the actuarial balance by 0.02 percentage points of payroll, increases in assumed potential GDP improved the balance by 0.03 percentage points, and other factors improved the balance by 0.07 percentage points.

Changes in disability assumptions, especially from lower assumed applications, improved the actuarial balance by an additional 0.07 percentage points of payroll relative to last year. As many workers with disabilities went on expanded unemployment benefits in 2020 and then returned to the workforce in 2021 and 2022, this improvement has helped extend the life of the SSDI trust fund.

The Trustees previously projected SSDI trust fund would be exhausted in 2057; they now estimate it will remain solvent beyond the 75-year window. Still, policymakers should continue to support improvements to disability program, particularly those that can help to support individuals with disabilities to remain in or return to the workforce.

Meanwhile, new demographic assumptions worsened Social Security’s 75-year shortfall by 0.04 percentage points of payroll, mainly as a result of historically low birth rates. Other factors, such as lower estimates of lawful permanent residents and higher death rates worsened the 75-year shortfall by 0.01 and 0.02 percentage points, respectively. The Trustees assume the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to cause lower legal immigration levels and higher death rates.

Most of the remaining change is due to the new projection window. Including the year 2096 in the Trustees 75-year solvency projections worsened the 75-year actuarial imbalance by 0.06 percentage points of payroll.

Importantly, the Trustees economic assumptions appear in many ways outdated. For example, they assume a 3.8 percent cost-of-living adjustment next year, which would actually require substantial deflation in the coming months. They also project inflation to normalize next year, while most forecasters believe it will remain elevated at least into next year, if not longer.

The overall improvement of Social Security’s fiscal outlook is a departure from the downward trend that’s persisted for more than a decade. While Social Security’s projected 75-year shortfall is 3 percent better than a year ago, it is 28 percent worse than in 2015 and 78 percent worse than it was in 2010 – when the shortfall was only 1.92 percent of payroll.

Even with this year’s improvement, Social Security’s 75-year shortfall is the second largest it has been since before the 1983 reforms.

Delaying Fixes to Social Security is Costly

Changes must be made in order to ensure Social Security’s solvency, and the sooner the better.

In their report, the Trustees recommend that “lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust to them.” Quick action would also give policymakers choices in making targeted adjustments, enhancing benefits for vulnerable populations, and achieving the added benefit of pro-growth reforms.

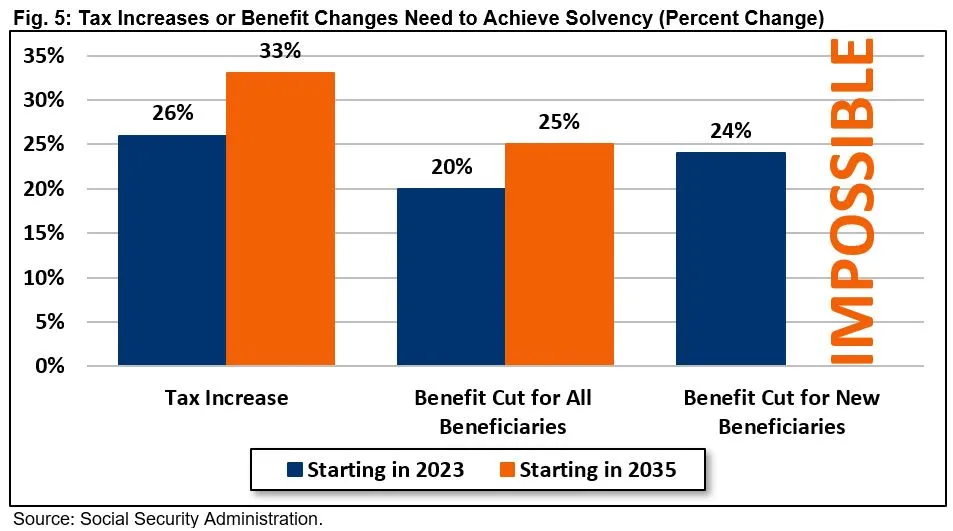

Delaying action until 2035 would make the needed tax increases or benefit reductions about 25 percent larger than if action were taken today. According to the Trustees, 75-year solvency could be achieved with a 26 percent (3.24 percentage point) payroll tax increase today but would require a 33 percent (4.07 percentage point) increase in 2035. Similarly, Social Security solvency could be achieved with a 20 percent across-the-board benefit cut today, which would rise to 25 percent by 2035. Benefit cuts for new beneficiaries would need to be 24 percent if imposed today, but even eliminating benefits for new beneficiaries in 2035 wouldn’t be enough to prevent insolvency.

Thoughtful trust fund solutions would not only prevent deep, across-the-board benefit cuts, but could also support economic growth, reduce inflationary pressures, and improve the nation’s fiscal outlook. We recently published ten options to improve Social Security solvency – including several benefit and revenue changes. Other proposals can be designed with our Social Security Reformer tool.

The closer we get to insolvency, the fewer of these options remain available.

Conclusion

The Social Security Trustees continue to warn that the program is significantly out of balance and just years from insolvency. Without reforms, Social Security will not to be able to pay full benefits to many current beneficiaries, let alone today’s workers and future generations. Action must be taken soon to avoid a 20 percent across-the-board cut to all beneficiaries in just 13 years.

Though changes in economic assumptions have slightly improved the trust fund outlook, it has not fundamentally changed its trajectory. The Trustees’ report also appears to rely on outdated economic assumptions that don’t consider the most recent inflation nor slowing growth.

Nevertheless, the Trustees project Social Security faces a 75-year shortfall of 3.4 percent of taxable payroll, which is 78 percent larger than projected in 2010 and means policymakers need to enact substantial revenue or benefit changes, or both, sooner rather than later.

Fortunately, many well-known options to fix Social Security’s finances exist and could be enacted and implemented with political will. A number of comprehensive plans already exist to restore solvency, and our Social Security Reformer Tool allows anyone to design their own. Policymakers should also consider pursuing new, innovative solutions to promote economic growth and improve retirement security in concert with addressing the program’s finances.

Policymakers cannot wait much longer to enact thoughtful Social Security reforms.

Tags

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image