Analysis of CBO's May 2022 Budget and Economic Outlook

Today, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its May 2022 Budget and Economic Outlook, its first baseline in almost a year. CBO’s new projections incorporate the recent surge in inflation, as well as other legislative, economic, administrative, and technical changes since July 2021. CBO’s new baseline shows:

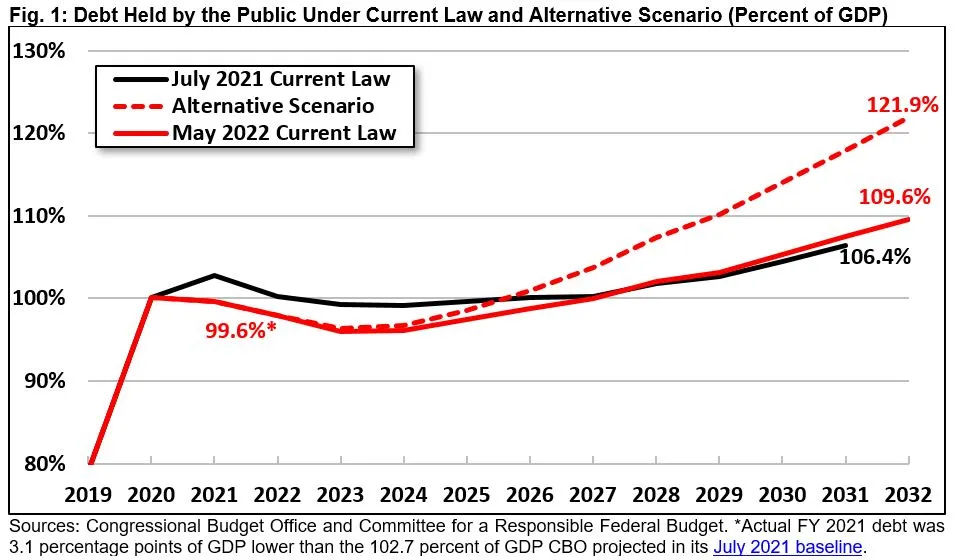

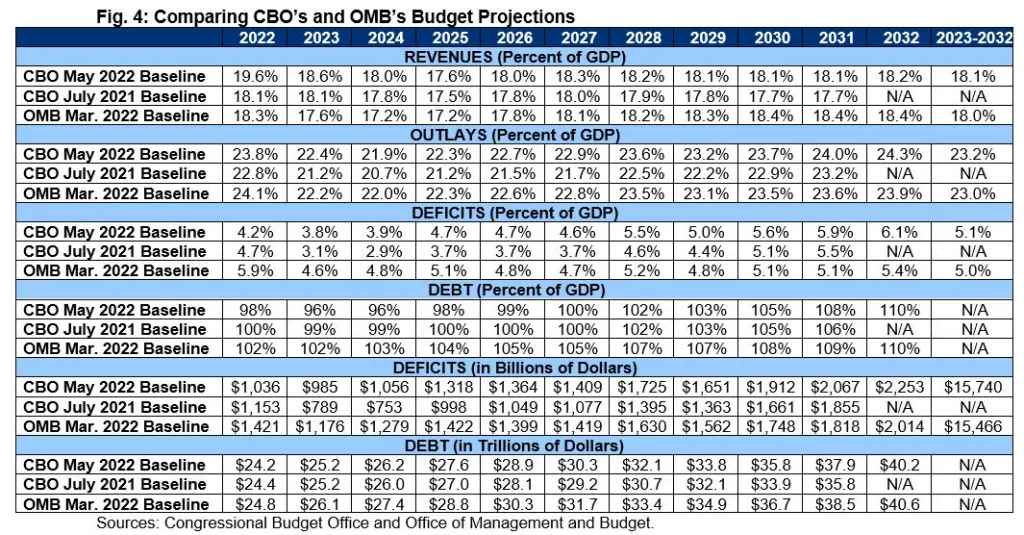

- Debt will rise to a record 110 percent of GDP by FY 2032, after dropping to 96 percent by 2023 as a result of the economic recovery and high inflation. Prior to the COVID pandemic, debt was 79 percent of GDP. In nominal dollars, debt will grow by more than $16 trillion to over $40 trillion by the end of FY 2032. If Congress extends various expiring policies, debt would be even higher.

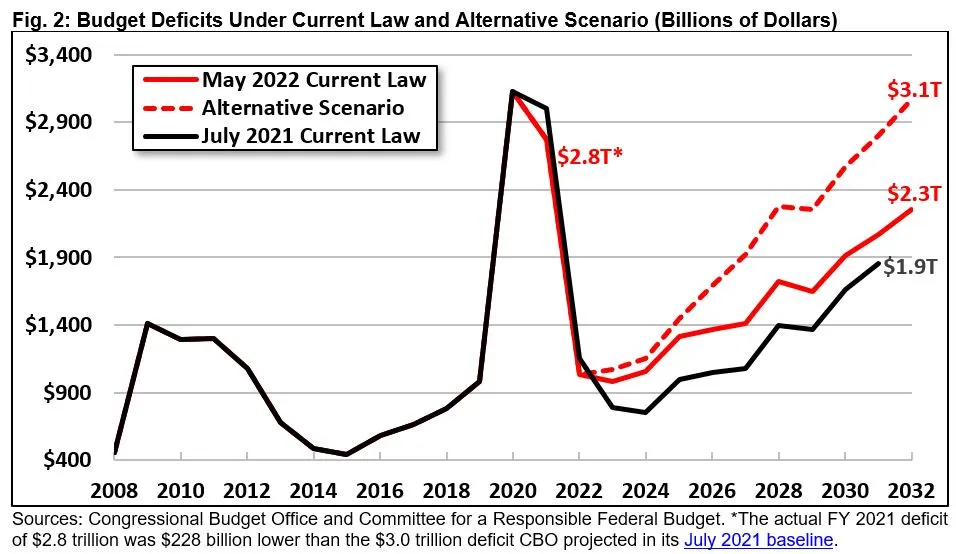

- Deficits will total $15.7 trillion (5.1 percent of GDP) over the next decade. As COVID relief ends and revenue surges, CBO projects the deficit will fall to $1.0 trillion (4.2 percent of GDP) in FY 2022, down from $3.0 trillion per year in 2020 and 2021, but then will rise to $2.3 trillion (6.1 percent of GDP) by 2032.

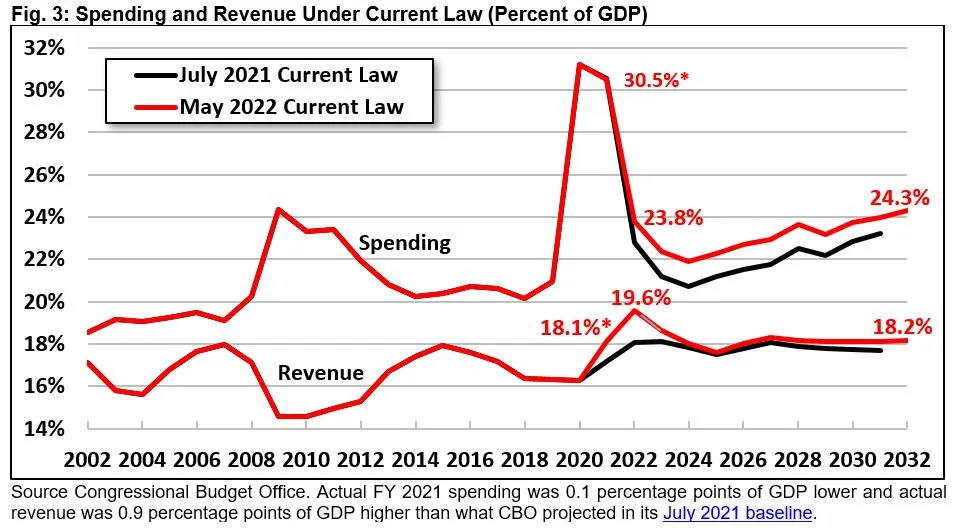

- Spending will rise while revenue will flatten. Revenue will rise from 18.1 percent of GDP in FY 2021 to 19.6 percent in 2022 but will return to an average of 18.1 percent per year through 2032. Spending will fall from 30.5 percent of GDP in FY 2021 to a low of 21.9 percent in 2024 as COVID relief ends, but then it will rise to 24.3 percent of GDP by the end of the budget window. Nominal interest spending alone will triple, reaching a record 3.3 percent of GDP by 2032.

- The fiscal outlook is worse than last year. Though CBO projects near-term debt to be a lower as a share of GDP than it did in July 2021, it expects deficits to be $2.4 trillion larger over ten years and debt-to-GDP about one percentage point higher in FY 2031. This is largely driven by legislative changes.

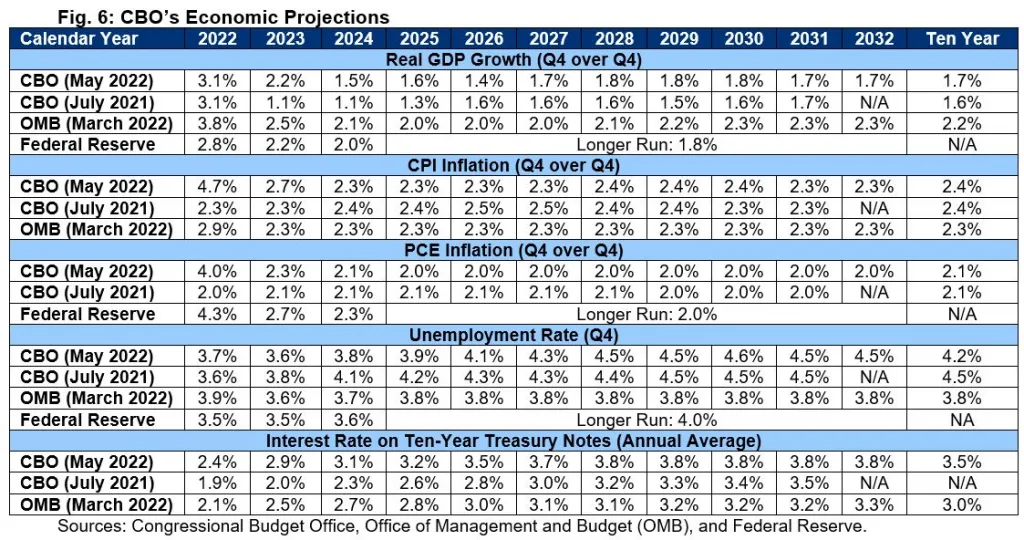

- CBO projects surging inflation will normalize, while interest rates rise. CBO estimates CPI inflation will total 4.7 percent in CY 2022, 2.7 percent in 2023, and 2.3 percent per year thereafter. CBO projects the interest rates on ten-year Treasury notes will rise from 1.5 percent at the end of 2021 to 2.7 percent by the end of 2022 and 3.8 percent in 2028 and beyond. CBO projects unemployment will remain low through next year, then rise to 4.5 percent by the end of 2032. Finally, CBO projects real GDP will grow by 3.1 percent in 2022, by 2.2 percent in 2023, and by roughly 1.7 percent per year thereafter.

CBO’s baseline confirms our debt is on an unsustainable track, headed to a new record. Such high and rising debt levels will slow income growth, increase the share of the budget devoted to interest payments, and leave the United States increasingly vulnerable to threats, both foreign and domestic. Given high debt and surging inflation, policymakers should act soon to enact a deficit-reduction plan.

Debt Will Decline in the Near-Term Before Resuming an Upward Trajectory

Since the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, federal debt held by the public has risen by $7 trillion. Through the end of FY 2032, CBO projects debt will grow by another $16 trillion, exceeding $40 trillion.

As a share of the economy, debt also rose dramatically over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, from over 79 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the end of FY 2019 to nearly 100 percent at the end of 2021. Largely because of the effects of higher inflation on GDP, however, CBO projects a short-term decline in debt-to-GDP to 96 percent by FY 2023. After that, debt will resume an upward trajectory, exceeding the size of the economy by FY 2027 and reaching 110 percent by the end of 2032.

Debt levels could be significantly higher if policymakers extend most expiring tax cuts and grow annual appropriations with the economy rather than inflation. Under one such alternative scenario, debt would exceed the size of the economy by FY 2026 and reach 122 percent of GDP by the end of FY 2032. In the coming days, we will release an analysis showing how high debt could rise under a variety of scenarios.

As we’ve explained before, high debt has adverse and potentially dangerous consequences. Rising debt slows wage and income growth, increases federal interest payments, hinders our ability to respond to recessions or emergencies, places an undue burden on future generations, and heightens the risk of a fiscal crisis.

The United States Faces Large Budget Deficits

CBO projects budget deficits will total $15.7 trillion, or 5.1 percent of GDP, over the next decade.

After rising from $984 billion (4.7 percent of GDP) in FY 2019 to an average of $3 trillion (13.7 percent of GDP) per year in 2020 and 2021, CBO estimates the budget deficit will fall to $1.0 trillion (4.2 percent of GDP) in 2022 as COVID relief expires and tax collections surge.

Beginning in FY 2024, deficits will rise again, reaching $1.7 trillion (5.5 percent of GDP) by 2028 and $2.3 trillion (6.1 percent of GDP) by 2032. The deficit in 2032 will be higher than any time outside of a major war or deep recession, and well above the historic average of 3.5 percent of GDP.

Deficits could be even higher if policymakers return to their pre-pandemic pattern of fiscal irresponsibility by extending most expiring tax cuts and growing annual appropriations with the economy rather than inflation.

Under an alternative scenario, deficits would total $20.3 trillion (6.5 percent of GDP) over the 2023-2032 budget window – $4.5 trillion (1.4 percent of GDP) more than under current law. The deficit would total $3.1 trillion (8.4 percent of GDP) in FY 2032 alone.

Spending and Revenue Will Continue to Diverge

High deficits and debt are driven by a disconnect between spending and revenue. Between FY 2023 and 2032, CBO projects spending will total $72.2 trillion (23.2 percent of GDP) while revenue will total $56.5 trillion (18.1 percent of GDP). In other words, projected revenue will only be enough to cover just over three-quarters of projected spending.

As a result of the aggressive federal response to the COVID-19 crisis, spending rose from $4.4 trillion (21.0 percent of GDP) in FY 2019 to $6.8 trillion (30.5 percent of GDP) in 2021. As COVID relief expires, CBO projects spending will fall below $6 trillion to a low of 21.9 percent of GDP in 2024 before rising to nearly $9 trillion – or 24.3 percent of GDP – by 2032.

On the revenue side, CBO estimates receipts will surge between FY 2021 and 2022, from $4.0 trillion (18.1 percent of GDP) to $4.8 trillion (19.6 percent of GDP), but then fall back to an average of 18.1 percent of GDP per year thereafter.

The near-term revenue surge is due to a combination of a strong economic recovery, rapid inflation, large capital gains in tax year 2021, the deferral of some taxes through COVID relief measures, and other factors.

Beyond FY 2022, CBO expects revenue to fall as a share of GDP relative to the 2022 level while growing in nominal dollars. Revenue will fall to 18.6 percent of GDP ($4.9 trillion) in 2023 and to a low of 17.6 percent of GDP ($5.0 trillion) in 2025, then rise back to 18.2 percent of GDP ($6.7 trillion) by 2032, after many provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) have expired.

Spending growth beyond FY 2025 is largely driven by rising retirement, health care, and interest costs. Between 2022 and 2032, CBO projects that Social Security and health care spending will each grow by roughly one percentage point of GDP, while interest will rise by 1.6 percentage points of GDP.

Indeed, CBO projects interest costs will more than triple from $400 billion in FY 2022 to $1.2 trillion by 2032. Interest will reach a record 3.3 percent of GDP, surpassing the prior record of 3.2 percent set in 1991. Over the full decade, interest costs will exceed $8 trillion – comprising more than half the deficit and consuming all revenue outside of individual income and payroll taxes.

Changes in revenue, meanwhile, are driven by ongoing inflation and economic growth, declining capital gains realization, reduced Federal Reserve remittances to the Treasury, the scheduled expiration of many of the individual income tax provisions in the TCJA (mostly in 2026), and other factors.

Spending could be higher and revenue lower if policymakers extend most expiring tax cuts and grow annual appropriations with the economy rather than inflation. Under an alternative scenario, revenue would reach only 17.1 percent of GDP by FY 2032 while spending would grow to 25.1 percent of GDP.

Changes from CBO's July 2021 Budget Projections

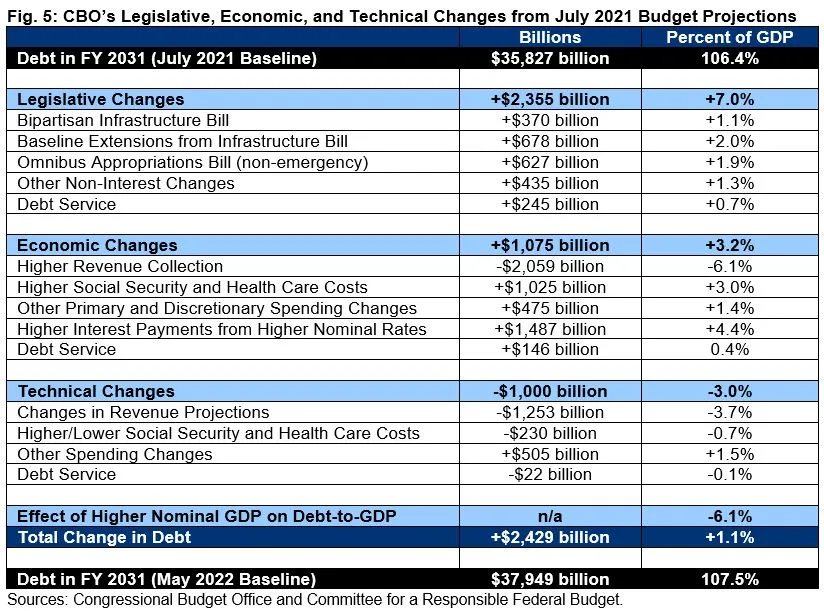

CBO now projects deficits to be $2.4 trillion higher through FY 2031 and debt-to-GDP to be 1.1 percentage points higher in 2031 than it did in its July 2021 baseline, primarily as a result of new legislation and related baseline assumptions.

Legislative changes increased projected deficits by nearly $2.4 trillion, including $370 billion from the direct effects of the bipartisan infrastructure bill and $627 billion from the FY 2022 omnibus bill. Economic changes increased projected deficits by another $1.1 trillion, with higher inflation and interest rates forecasts leading to $2.1 trillion more revenue but $3.1 trillion more spending.

Technical changes reduced projected deficits by $1 trillion, with nearly $1.3 trillion of higher-than-expected revenue. At the same time, administrative actions such as extending the student debt repayment pause and increasing monthly Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits increased deficits and reduced the savings from technical adjustments.

Relative to CBO’s July 2021 projections, these factors would increase debt-to-GDP by 7.2 percentage points in FY 2031. However, higher nominal GDP projections – mainly from higher inflation – reduce debt-to-GDP by 6.1 percentage points in FY 2031. On net, debt is 1.1 points higher.

CBO's Economic Projections

CBO’s new baseline incorporates a number of economic changes, including the recent surge in inflation. After growing by 6.7 percent in calendar year (CY) 2021, CBO estimates Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation will grow 4.7 percent in 2022, 2.7 percent in 2023, and normalize at about 2.3 percent per year thereafter. Similarly, Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation will total 4.0 percent in 2022, 2.3 percent in 2023, and normalize at about 2.0 percent per year thereafter.

CBO also expects the economy will continue to recover, with real GDP growing by 3.1 percent in CY 2022, 2.2 percent in 2023, and by about 1.7 percent per year after that. CBO expects the unemployment rate to fall from 4.2 percent at the end of 2021 to 3.6 percent by the end of 2023, before rising to 4.5 percent by the end of 2032.

The interest rate on a ten-year Treasury note is currently 2.8 percent, up from 1.4 percent in CY 2021. CBO projects the interest rate on ten-year Treasuries will rise further to 3.8 percent by 2028 and beyond. The interest rate on three-month Treasury bills is currently 1.1 percent, up from close to 0 percent in 2021. CBO projects interest rates on three-month Treasuries will rise further to 2.6 percent by 2025, then drop to 2.3 percent by 2032.

Overall, CBO’s economic forecasts are similar to other forecasters, though differ in some ways. For example, its PCE inflation projections of 4.0, 2.3, and 2.1 percent over the next three years, respectively, are only moderately below the Federal Reserve’s forecast of 4.3, 2.7, and 2.3 percent. CBO’s interest rate projections are, on average, about 50 basis points above OMB’s.

Conclusion

CBO’s latest budget projections confirm that the country is on an unsustainable fiscal trajectory, with debt and interest costs both on course to reach record shares of the economy by FY 2032. The expiration of COVID relief and rising inflation will offer a temporary one-time reprieve, but debt will continue to rise as policymakers continue to borrow instead of paying for their priorities.

Substantial deficit reduction is needed to put the debt on a sustainable path, yet most of the political discourse has revolved around enacting new spending or tax cuts. Simply extending current tax cuts and maintaining discretionary spending as a share of the economy would boost debt to 122 percent of GDP by FY 2032, and more thereafter. This additional borrowing should not be allowed.

With inflation at a 40-year high, policymakers should enact near-term deficit reduction and reforms to assist the Federal Reserve in its effort to bring inflation back down. More importantly, they should enact long-term fiscal improvements to stabilize our debt and begin to reduce it as a share of the economy.

Getting the country on solid fiscal ground will require lowering health care costs, securing Social Security and other trust funds that are headed toward insolvency, raising additional revenue, limiting discretionary spending growth, and cutting other low-priority spending and tax breaks. The sooner we act, the better.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-