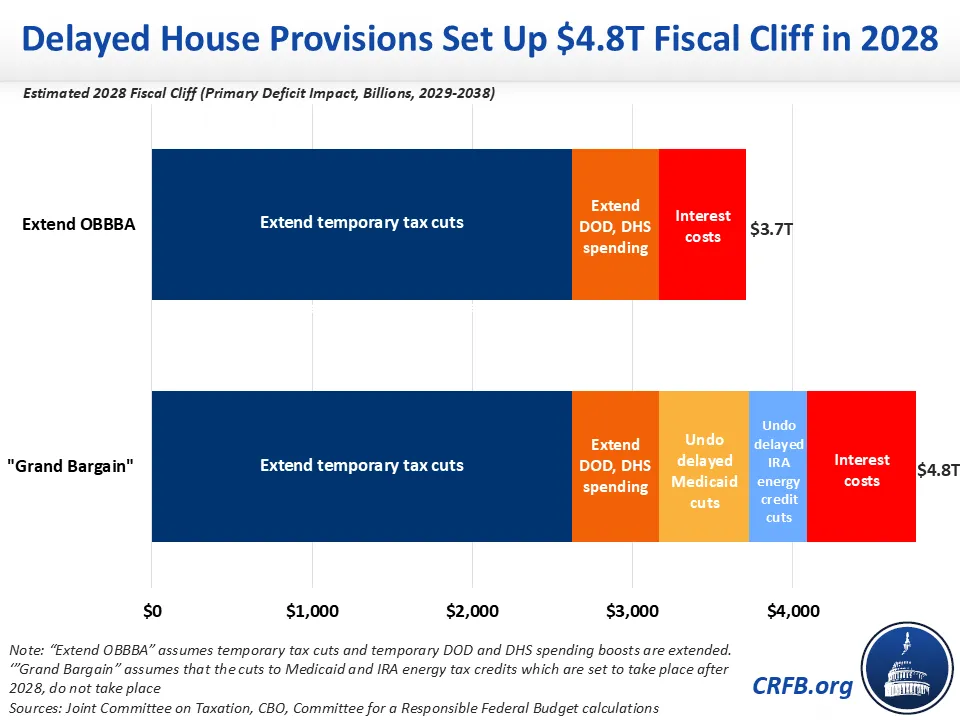

Reconciliation Bill Sets up $4.8 Trillion Fiscal Cliff in 2028

As written, the reconciliation bill being considered in the House of Representatives is set to increase the debt by $3.3 trillion between 2025 and 2034 after considering interest costs. This number is achieved only by relying on a series of timing gimmicks – many deficit-increasing provisions are scheduled to end in 2028, while many deficit-reducing provisions will not begin until after 2028. This could create a looming 2028 fiscal cliff of up to $4.8 trillion over a decade.

The reconciliation bill relies on front-loaded tax cuts and spending and back-loaded savings to keep its ten-year impact within the reconciliation targets. But with these arbitrary expirations looming, in 2028, lawmakers may face immense pressure to extend temporary tax cuts, re-up spending increases, and undo scheduled spending cuts.

We estimate that extending expiring provisions would increase debt (with interest) by $3.7 trillion between 2029 and 2038. Additionally canceling spending cuts would increase that debt increase to $4.8 trillion.

Among the provisions of the One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) lawmakers may feel pressure to extend or cancel include:

- New individual tax cuts – such as those related to tipped income, overtime pay, automobile loan interest; ‘MAGA accounts’ for newborns; and the increases to the Child Tax Credit, base standard deduction, and seniors’ standard deduction – will expire after 2028 and increase debt by roughly $1.6 trillion over the following decade if extended.

- Business tax cuts – such as the revival of 100 percent bonus depreciation for equipment, full expensing for research and experimentation, and expensing for factories – are set to expire after 2029 and increase debt by $1 trillion over the following decade if extended.

- New spending increases – mainly for defense, immigration, and border security – will peak around 2027, be expended by 2034, and add roughly $550 billion to debt if extended.

- New requirement and restrictions on Medicaid spending – such as work requirements, address verification and cost sharing – will be implemented in 2029 or 2030 under the current bill (there is discussion of changing this), reducing debt by $550 billion.

- Eligibility for key clean energy tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act will end after 2028 (there is discussion of changing this), reducing debt by $350 billion.

In 2028 and 2029, policymakers will face a decision: do they allow taxes to increase on individuals and businesses, and allow the funding boosts to defense and homeland security to dissipate? Many current policymakers likely intend for these policies to be extended and will face intense pressure to continue them. If policymakers reach this 2028 fiscal cliff and extend those provisions, debt would increase by $3.7 trillion through 2038, including $3.2 trillion of primary deficit increases and an additional $550 billion of interest costs.

Especially given the two elections that will take place before the end of 2028, there may also be interest at that point in undoing many of the deficit-reducing measures this bill defers until later. If such a “Grand Bargain” is negotiated between the parties in 2028, we estimate that debt would increase by $4.8 trillion, including $4.1 trillion of primary deficit increases and $700 billion in added interest costs.

The current reconciliation bill is a prime example of policymaking under a fiscal cliff. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) sunset many provisions early in order to lower the perceived deficit impact of that bill. Now that these provisions are about to expire, policymakers are extending and even expanding the “temporary” TCJA provisions. In many cases they rely on “current policy” gimmicks to claim the extensions have no deficit impact. Lawmakers also included many deficit-reducing provisions in the TCJA, such as increases to taxes on foreign and domestic businesses and capping the state and local tax deduction. However, this reconciliation bill unwinds many of these pay-fors. It is easy to see how this process could be repeated at the next fiscal cliff in 2028.

The most pro-growth, honest, and responsible way to design tax and spending reform is to do so in a permanent and deficit-reducing (or at least deficit-neutral) manner. Timing gimmicks create confusion and inefficiency and are often used to hide the true intended deficit impact of policies. Although the fiscal impact of any extensions should be fully recognized and offset, historic and recent experience suggests future lawmakers are likely to add dramatically to the debt when the next fiscal cliff arises.

Rather than creating this fiscal cliff, current lawmakers should either remove or make permanent any artificially temporary policies and should fully offset any tax cuts or spending so that the package reduces rather than adds to the debt. This could be accomplished by scaling back new tax priorities and further building on proposed offsets.