New Senate Tax Bill Hides Over $500 Billion of Gimmicks

NOTE: This is an old version of this analysis based on a version of the bill considered by the Senate Finance Committee. The bill was later modified. See our analysis of the Senate-passed version.

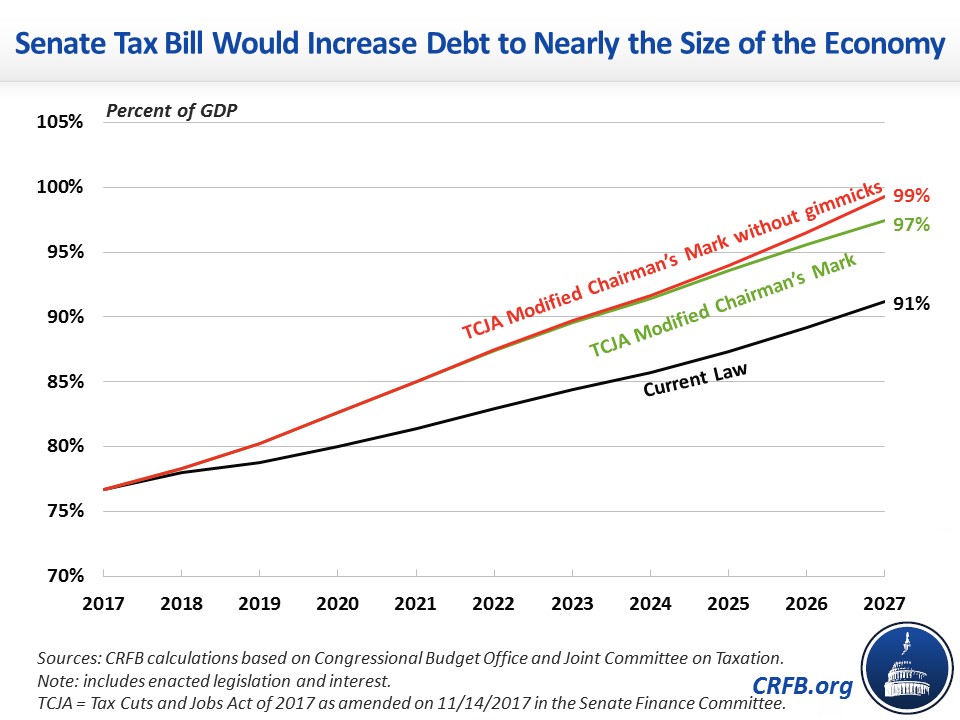

The new Senate Finance Chairman's mark of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would cost $1.41 trillion and significantly worsen our already unsustainable budget outlook. However, even this cost masks $515 billion of gimmicks the bill contains and doesn't include interest costs. Ultimately, the Senate tax plan could add $2.2 trillion to the debt. As a result, trillion-dollar deficits would return by 2020 and debt would exceed the size of the economy in just over a decade.

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), the TCJA as written would increase deficits by $1.41 trillion over ten years. However, the bill hides its true cost by having major provisions in the bill arbitrarily expire, making them look much cheaper than they actually are.

| Policy | Ten-Year Cost |

|---|---|

| Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as scored by JCT | $1.41 trillion |

| Sunsetting the individual tax provisions after 2025 | $240 billion |

| Sunsetting full expensing after 2022 (including expansion) | $115 billion |

| Amortizing R&E expenses after 2025 | $60 billion |

| Making foreign tax provisions more strict after 2025 | $55 billion |

| All other sunsets/backloading | $45 billion |

| Total primary "real" cost | $1.9 trillion |

| Interest costs on base bill | $280 billion |

| Additional interest costs of budget gimmicks | $25 billion |

| Total "real" cost | $2.2 trillion |

Source: CRFB calculations based on 11/14/2017 JCT estimate of the Chairman's Modified Mark of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and CBO data.

Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

The most egregious example: the bill allows almost all of its tax provisions on individuals to expire suddenly after 2025. Clearly this sunset, similar to the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, is only included to get around the Byrd rule that prohibits reconciliation bills from increasing deficits after the ten-year window. We estimate that if these provisions were all permanent, it would add roughly $240 billion to the cost of the bill.

The gimmicks don't stop there. The bill still arbitrarily allows full business expensing to expire after five years but expands it by allowing film, TV, and live theater costs to qualify for temporary expensing as well. Continuing the provision would add to costs. In addition, the bill requires research and experimentation (R&E) expenses to be amortized over five years but only starting in 2026. This is not a credible offset since it is very backloaded, goes in the opposite direction of the full expensing the bill otherwise allows and intends to be permanent, and starts when the rest of the provisions expire.

The bill also suddenly creates more strict rules for net operating loss deductions, meal deductions, and foreign taxation starting in 2024 and later years. Finally, the bill allows a paid family and medical leave credit and several alcohol-related provisions that reduce revenue to expire after 2019. All of these gimmicks add another $275 billion to the cost of the bill for a grand total of $515 billion of gimmicks. Therefore, the cost of the tax bill when removing gimmicks is actually $1.9 trillion over ten years. This toal does not count delaying the corporate rate cut until 2019, which reduces the bill's apparent ten-year cost but doesn't change the ultimate effect.

Even this total is not the full cost of the bill since it doesn't account for interest costs. The initial bill would add $280 billion to interest costs while the gimmicks would add another $25 billion, making the grand total for the bill $2.2 trillion.

Even without these extensions, the tax bill would be expensive enough to lift deficits to larger than $1 trillion by 2020 (compared to $780 billion under current law, including the cost of recent disaster relief) and increase the ratio of debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to 97 percent of GDP by 2027 (compared to 77 percent today and 91 percent by 2027 under current law). With expiring provisions extended, debt would reach 99 percent of GDP by 2027 and exceed the size of the economy the very next year. This high level of debt is likely to dampen or even ultimately reverse the pro-growth effects of tax reform.

Adding $1.4 trillion to the debt is bad enough, but potentially adding $2.2 trillion to the nation's credit card would be even more fiscally irresponsible. Lawmakers should identify additional base broadening measures or scale back some of the bill's tax cuts to ensure the legislation is fully paid for without resorting to budget gimmicks like the ones already included. Tax reform should not come at the expense of future generations.