Income Has Risen Through the COVID Recession But That May Soon Change

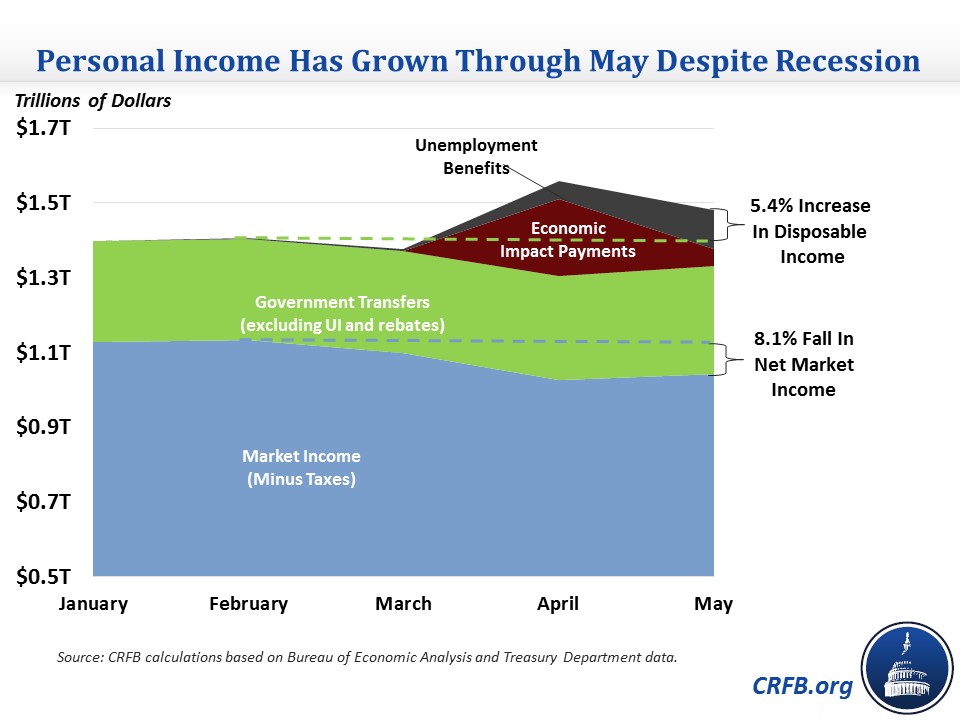

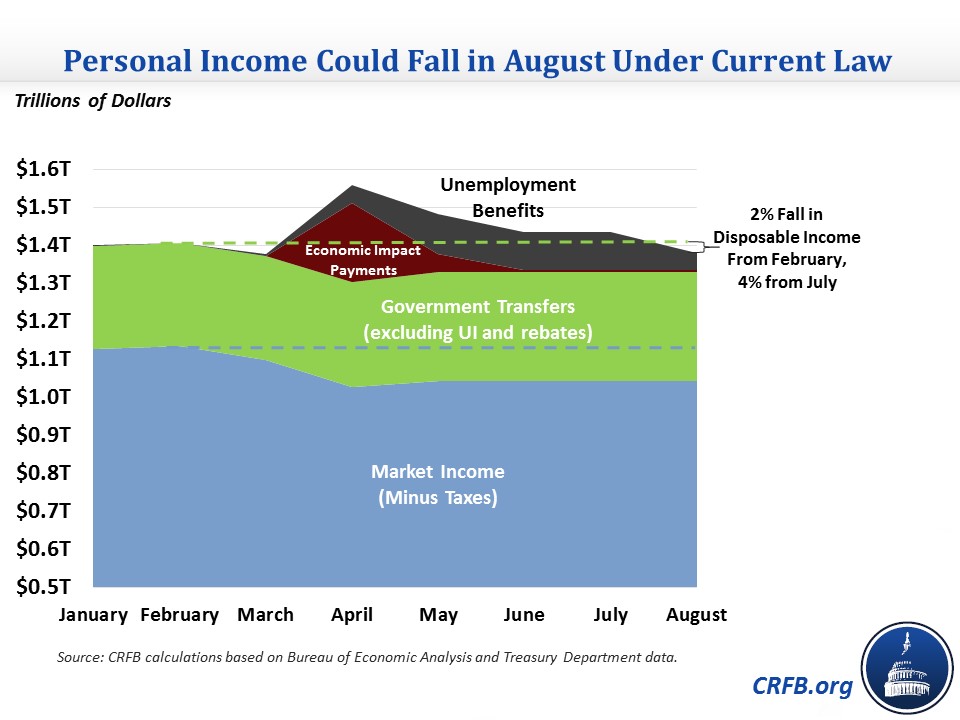

Despite the sharpest economic contraction is modern history, personal income has actually grown since the COVID-19 crisis started through May. While market income shrank by 8 to 9 percent between February and May of 2020, we estimate total disposable income grew by 5 to 7 percent.

This increase is more than entirely the result of aggressive fiscal and monetary actions taken to stabilize the economy, in particular the expansion of unemployment benefits and distribution of Economic Impact Payments. If these and other income supports fade later this month and over the course of the summer as scheduled, we project income will fall substantially in August.

This blog post is a product of the COVID Money Tracker, a new initiative of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget focused on identifying and tracking the disbursement of the trillions being poured into the economy to combat the crisis through legislative, administrative, and Federal Reserve actions.

Output is Way Down, but Income is Way Up

The COVID-19 pandemic sent shockwaves through the economy and caused a sharp, sudden contraction. Between February and May, employment dropped by about 20 million people, economic output fell by an estimated 10 to 15 percent, and nearly half of households reported at least some loss in employment income.

The first-order economic damage would likely have been far worse without aggressive legislative, executive, and Federal Reserve actions, including the Paycheck Protection Program to support small businesses and worker retention, new liquidity measures and lending facilities, and over $1 trillion of support for consumption and demand. Even still, between February and May market income fell by 9.2 percent, and after-tax market income fell by 8.1 percent. Incorporating the effects of most government transfers such as Social Security and SNAP (food stamps), income still fell by 5.3 percent.

However, total disposable income actually rose by 5.4 percent between February and May. In other words, income grew as much over three months of deep economic contraction as the preceding 15 months of uninterrupted economic growth. Driving this growth is the nearly $100 billion of unemployment benefits paid in May – about three quarters the result of expansions in the CARES Act – and another $50 billion from one-time $1,200 per person Economic Impact Payments called for under the CARES Act.

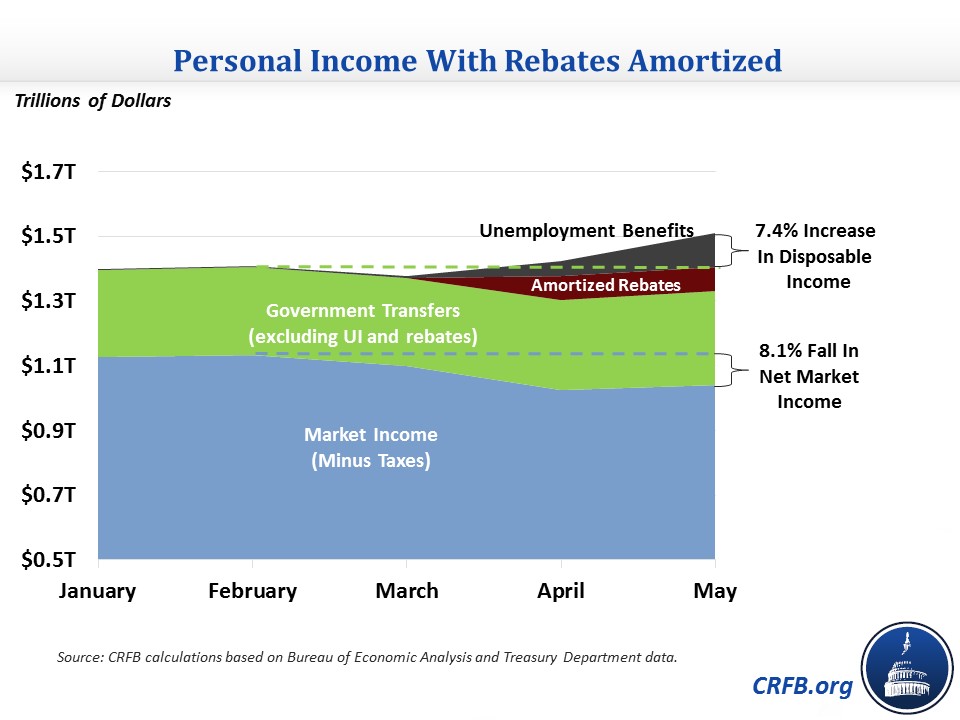

Because the Economic Impact Payments provide only a one-time check, they lead to a somewhat distorted view of income. If instead we assume people treat this funding as supplementing four months of income (i.e. $300 per month from April through July), income would be up by 7.4 percent between February and May.

This is a tremendous increase in income for any three-month period – it took 20 months for income to grow that much previously – and is especially unprecedented given the simultaneous collapse of economic activity.

Income Could Drop Substantially in August

Market income and is likely to be higher in June than in May, and disposable income will be higher as well if economic impact payments are amortized. Income may also be higher in July than in June. But barring new legislation and/or surprisingly positive economic or public health developments, income is likely to face a large cliff in August as fiscal relief starts to expire. Specifically, we project disposable income will fall to roughly 2 percent below February's levels. Compared to July, that would be a 4 percent drop, or an 8.5 percent drop relative to our amortized measure.1

Driving this reduction is the scheduled expiration of the temporary $600 per week boost in unemployment benefits and the almost completed disbursement of Economic Impact Payments, which will also have been largely spent at that point. State level budget cuts (or tax hikes) necessary to balance their budgets (the new fiscal year started July 1) will also reduce income, as well as depletion of many Paycheck Protection Program dollars (the application deadline is August 8) and the ongoing economic threat of continued virus spread and resurgence.

To prevent income from falling to below February levels, market and transfer income would need to rise by a combined $25 billion in August, – the equivalent of $300 billion a year. For context, the $600 unemployment benefits increase provides roughly $50 billion per month in income, so a partial extension could be sufficient to close this gap. Fiscal support would need to be somewhat larger than $25 billion to compensate for inflation and/or maintain income closer to July levels.

As policymakers consider another round of COVID relief, they should consider the size of timing of the upcoming income cliff, as well as the projected output gap; economic, public health and societal needs; the direct cost of any legislation; and the opportunity cost of the choices they make.

*****

The fiscal response to the pandemic has directly impacted household finances, and debate among policymakers continues as to what, if any, stimulus measures Congress will approve or extend to further aid the recovery process. We will continue to monitor how the money is spent and its effects on the economy as part of our COVID Money Tracker program. Our recent webinar discussing these issues and the progress of the federal response can be found here.

1 Importantly, our income figures are somewhat conservative. They assume market and transfer income minus taxes remains flat between May and August, when evidence shows the economy and jobs picture has improved (though it may be somewhat stalled now). On the other hand, higher market income would lead to higher taxes and lower unemployment benefits than in our projections – and there remains a possibility that the economy will contract some as the virus spreads further.