How Big Should the Next COVID Package Be?

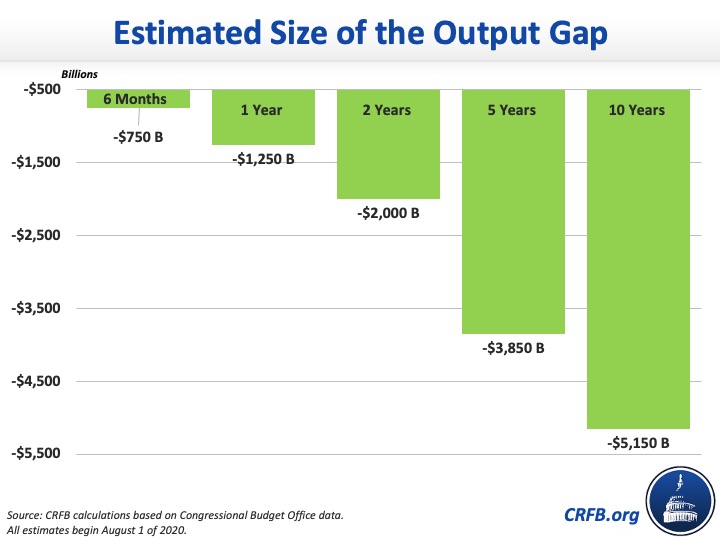

With over $2 trillion of fiscal support now out the door, Congress is considering additional legislation to help stabilize the economy, support the recovery, and address the effects of the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis. As policymakers negotiate the size of the next package, they should consider the size of output gap they intend to close. Based on recent data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), we estimate the output gap will total roughly $750 billion over the next six months or $2 trillion over two years. The funds needed to fully close this gap will depend on the fiscal multiplier of the specific policies and could be anywhere from $300 billion to $3 trillion for just the next six months.

This blog post is a product of the COVID Money Tracker, a new initiative of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget focused on identifying and tracking the disbursement of the trillions being poured into the economy to combat the crisis through legislative, administrative, and Federal Reserve actions.

The output gap is the difference between expected economic output under current law and possible economic output if the economy were operating at full potential. While an economic relief package should be built from the bottom up based on the needs of various sectors of the economy and society, its total size should be determined, at least in part, by the output gap it aims to close or reduce.

Based on recent economic projections from CBO, we estimate the output gap will total $750 billion over the six-month period between August 1, 2020 – when expanded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits end under current law – and February 1, 2021, shortly after Inauguration Day. Looking further, we project the output gap will total $1.3 trillion over a full year, $2 trillion over two years, $3.9 trillion over five years, and $5.2 trillion over ten years.

During a typical recession, fiscal policy can reduce the output gap by inducing consumption or expanding government purchases, thereby supporting the return of unemployed workers and use of underutilized machines and buildings. The effectiveness of this stimulus is based largely on fiscal multipliers, which determine how much economic output is achieved for each dollar of tax cuts or spending increases enacted. Different policies can have very different multipliers. For example, in 2010, CBO estimated that each dollar of expanded unemployment benefits would produce $0.70 to $1.90 of economic activity, payroll tax relief would produce $0.40 to $1.30, aid to states would produce $0.40 to $1.20, and expanded Social Security benefits would produce $0.30 to $0.90. One more recent estimate from Federal Reserve economists suggests the fiscal multiplier for the COVID-19 fiscal response is likely about 1 – meaning each dollars of fiscal support would reduce the output gap by about one dollar.

Due to social distancing measures and fear that COVID-19 will continue to spread, it is virtually impossible that any fiscal policy could eliminate the output gap in the near-term. If restaurants can only operate at one-quarter capacity and customers are afraid to visit them, for example, no amount of fiscal stimulus can force their economic activity to return to pre-COVID levels. However, fiscal support could theoretically spur enough economic activity to shrink the size of the near-term output gap and to cover the remainder of the gap over time once the public health crisis is under control.

The cost of achieving this goal would depend on the average fiscal multiplier in the next emergency relief package. For example, with a fiscal multiplier of 1.5 it would take $500 billion to close the output gap over the next six months, $850 billion to close it over the next year, and $1.4 trillion over two years. In contrast, with a 0.5 multiplier, it would take $1.5 trillion of funding to close the output gap over the next six months, $2.5 trillion to close it over the next year, and $4 trillion to close it over the next two years.

Of course, policymakers could choose to spend less than is needed to close the output gap to support a more gradual recovery; for example, if they only wanted to close the "personal income" gap, they could do so with $200 billion of transfers over six months, $550 billion over a year, and $1.4 trillion over two years. On the other hand, lawmakers might also want to spend more than is needed to close the output gap in order to cover other non-macroeconomic needs – for example, to shore up state and local budgets or expand policies designed to mitigate, contain, or reduce the risk associated with COVID-19.

How Much Money Would It Take to Close the Output Gap?

| 6 months | 1 year | 2 years | 5 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25x multiplier | $2,950 billion | $5,000 billion | $8,000 billion | $15,450 billion |

| 0.5x multiplier | $1,500 billion | $2,500 billion | $4,000 billion | $7,700 billion |

| 1x multiplier | $750 billion | $1,250 billion | $2,000 billion | $3,850 billion |

| 1.5x multiplier | $500 billion | $850 billion | $1,350 billion | $2,600 billion |

| 2x multiplier | $400 billion | $650 billion | $1,000 billion | $1,950 billion |

| 2.5x multiplier | $300 billion | $500 billion | $800 billion | $1,550 billion |

| "Income Gap" | $200 billion | $550 billion | $1,350 billion | $3,450 billion |

Source: Congressional Budget Office and CRFB calculations. "Income gap" is a concept we use to describe the difference between actual personal income and potential personal income. To approximate potential personal income, we assume income would remain the same share of potential GDP as projected prior to the current crisis. The gap is small in the near-term due to existing government transfers.

Importantly, these figures do not account for the adverse consequences of higher debt – consequences that would be exacerbated by relying on low-multiplier stimulus for the next package and any future packages. With a fiscal multiplier of 0.25, for example, it would ultimately require more than $15 trillion of fiscal support to close to output gap over the next five years. This would boost debt from less than 100 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) today to 178 percent by 2025 and as a result GDP would likely be several percentage points lower over the long-run.

As policymakers negotiate the size of the next and future stimulus packages, they should consider the size of the output gap they intend to close or reduce and focus on policies which either deliver high economic multipliers or else serve other important public policy priorities relevant to the current crisis. The national emergency should not be used as an excuse to enact pet projects or costly but economically ineffective tax cuts and spending increases.