Pell Grant Program Still Faces Large Shortfall, Despite One-Time Fix

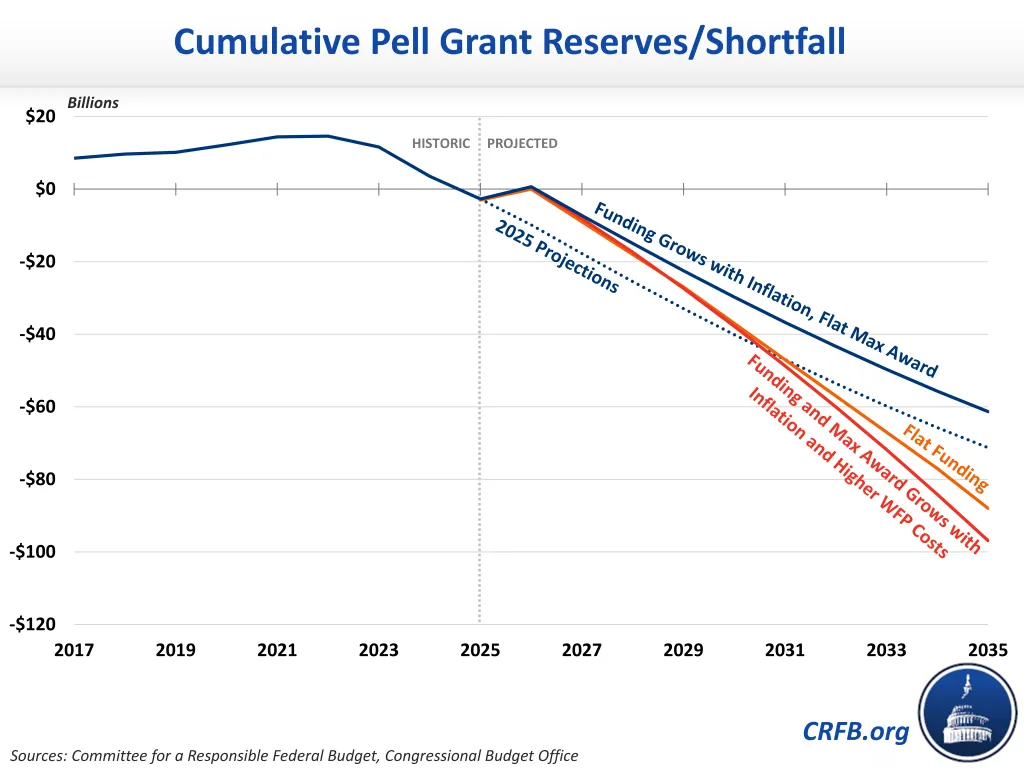

The Pell Grant program faces a large funding gap, despite the one-time infusion of funding enacted as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). Based on data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and accounting for provisions in OBBBA, we estimate the program faces a $61 billion to $97 billion ten-year shortfall.

Earlier this year, we estimated the Pell Grant program would run out of reserves in Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 and face a $71 billion to $111 billion shortfall between 2026 and 2034. OBBBA addressed part of this shortfall by providing $10.5 billion in one-time mandatory funding to shore up the program's reserves. However, the law also expanded eligibility to short-term workforce programs ("Workforce Pell"), which added new costs to the program. Using data from CBO and our own estimates, we find:

- The $10.5 billion one-time fix will delay reserve depletion by a couple of years but will not address the program's structural shortfall.

- Pell Grant costs will still exceed appropriations every year over the next decade, leading to a cumulative shortfall of at least $61 billion between 2026 and 2035.

- Under alternative scenarios, the Pell Grant program could face a cumulative ten-year shortfall of up to $97 billion.

- Workforce Pell could add between $2 billion (per CBO) and $6 billion (under alternative assumptions) to program costs.

While Congress did successfully address the Pell program’s near-term funding crisis, it kicked the can on fixing the longer-term structural imbalance between Pell Grant costs and funding.

OBBBA’s Cash Infusion Delayed Depletion of Pell Funds, But Added New Costs

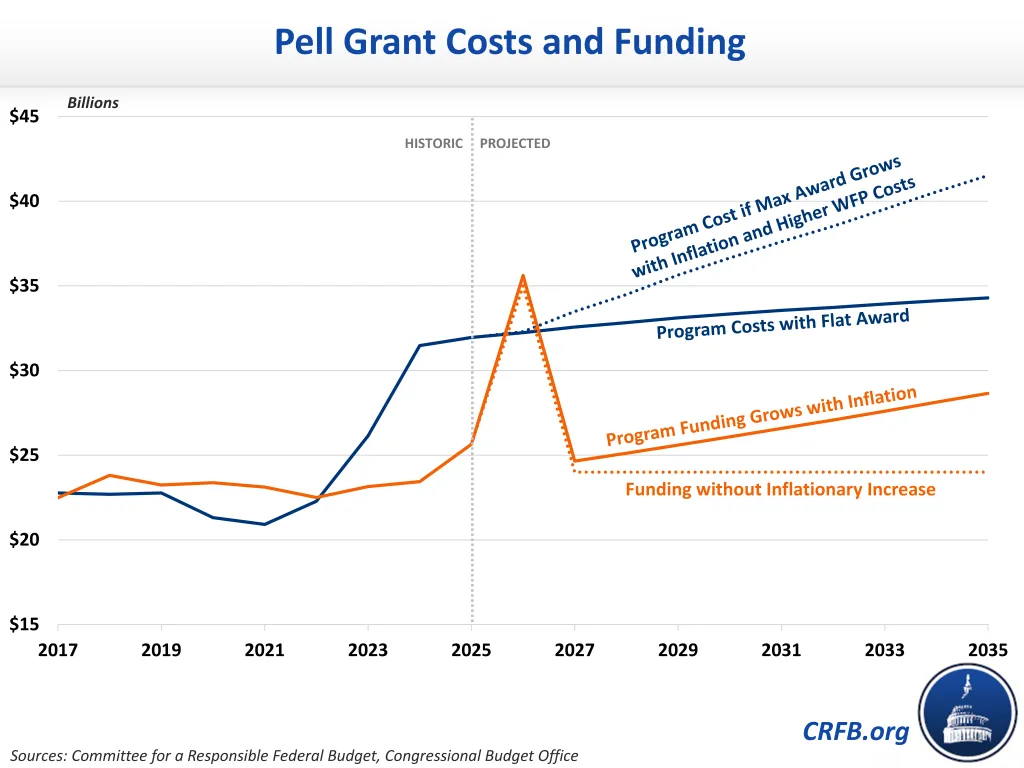

Prior to the passage of OBBBA, the Pell Grant program was set to run out of reserves in FY 2025, with a projected $3 billion shortfall by year's end, and faced a $71 to $111 billion funding gap through 2035. The $10.5 billion one-time appropriation included in OBBBA allowed Pell to avoid that immediate crisis and provided a temporary cushion. However, because program costs are expected to exceed funding by $6 billion to $11 billion annually going forward, this one-time fix will only delay reserve depletion by roughly two years.

The underlying structural gap between costs and appropriations remains unaddressed, and in fact was made worse under OBBBA. At the same time Congress provided a one-time funding boost, it also expanded Pell eligibility to short-term workforce programs. While proponents argue this will help workers gain credentials for in-demand jobs, it comes at a fiscal cost.

CBO estimates Workforce Pell will add roughly $2 billion to program costs over the next decade. We believe actual costs could be significantly higher – perhaps $6 billion or more – depending on take-up rates, how states and institutions implement the new program, and how the Department of Education interprets and enforces the accountability measures in OBBBA. History suggests that when new eligibility is created, enrollment often exceeds initial projections.

The Pell Grant Shortfall Remains Large

Accounting for both the $10.5 billion infusion and the addition of Workforce Pell costs, we estimate the program still faces a substantial shortfall.

If Congress grows the Pell program appropriations with inflation each year and holds the maximum award flat, the program faces a cumulative projected shortfall of roughly $61 billion over ten years. Assuming Congress holds funding flat and does not change the maximum award, we project a 10-year shortfall of $88 billion.

If both Pell funding and the maximum award both grew with inflation (historically it has increased by at least that much), and Workforce Pell enrollment grows faster than expected, the shortfall would grow to $97 billion.

On an annual basis, the Pell shortall is likely to average $8 to $9 billion in the early years and $6 to $13 billion by 2035.

Policymakers Should Address the Structural Shortfall

With a $61 billion to $97 billion gap between projected Pell Grant costs and projected funding, the one-time fix included in OBBBA merely delays the day of reckoning. Significant adjustments will still need to be made to boost funding and/or reduce costs.

The initial House Education and Workforce Committee proposal for OBBBA would have paid for the $10.5 billion cash infusion and saved at least $40 billion more (by our estimate) within the Pell program by changing the definition of full-time enrollment and eliminating Pell for those attending a program for less than half-time.

Other options exist to reduce the cost of the Pell program or to finance higher appropriations – for example, through further student loan reforms, reductions to the cost of higher education tax credits, or changes to non-education spending or revenue. The Department of Education can also play a role in controlling costs by ensuring that Workforce Pell is held to the highest accountability standards possible under the law to disqualify underperforming programs.

Policymakers should not wait until reserves are once again near depletion to act.