Debunking Debt Myths in the COVID Economy

Federal debt held by the public is slated to grow by roughly $4 trillion in fiscal year 2020 and exceed the size of the economy by year’s end. Much of this borrowing is inevitable and desirable – though not costless – in light of the current pandemic and economic crisis. However, the need for the federal government to borrow today does not mean borrowing can continue indefinitely without consequences.

Entering the crisis with trillion-dollar annual deficits – thanks in large part to recent tax cuts and spending increases – was a massive policy error.

Yet periods of depressed economic activity or acute one-time needs can benefit from substantial deficit spending. The aggressive fiscal actions taken in recent months have helped mitigate economic damage, support individuals and businesses, and limit human suffering. But additional borrowing still has costs.

During bad times, particularly when interest rates are low and the economy is operating well below potential, the costs of borrowing are generally smaller and usually outweighed by the benefits they produce. During normal times, the cost of borrowing grows and the benefits shrink or disappear.

As we’ve written before, the negative consequences of excessive debt include higher interest rates; slower income growth; large debt service payments; a reduced ability to respond to future recessions, emergencies or opportunities; a heightened dependency on foreign borrowing; further burdens on younger and future generations, and an increased risk of a financial, inflation, or other type of fiscal crisis.

Yet, numerous pervasive myths create the impression that these consequences do not exist. In this paper, we look at three of these myths, including:

- Low interest rates mean there is no cost of borrowing.

- Like after World War II, it will be easy to reduce debt after the pandemic.

- The Federal Reserve can keep buying our debt without consequences.

There are of course many more myths related to deficits and debt. In future papers, we will address others.

Myth #1: Low interest rates mean there is no cost of borrowing.

The interest rate on a 3-month Treasury bill is currently about 0.15 percent, and the rate on a 30-year bond is roughly 1.7 percent – both rates are near their lowest in history. Such low interest rates reduce the fiscal cost of debt, since low interest rates result in lower debt service payments. Low interest rates could also theoretically suggest that the issuance of government bonds is not “crowding out” much private investment, in which case the economic cost of debt would be lower than commonly believed.

While low interest rates reduce the fiscal cost of debt today, they do not eliminate this cost. Rather, they shift costs to the future. Borrowing increases the government’s total stock of debt and debt service payments. Without a plan to pay down that principal, it will almost certainly be rolled over into further debt at higher interest rates. Interest rates may remain low for some time, but they are practically guaranteed to rise from current levels. Higher debt also makes the country more vulnerable to any future interest rate increases or spikes – while interest rates can change quickly, debt reduction takes time.

Evidence also suggests that today’s low interest rates are in spite of, not because of, high deficits and debt – and that deficits continue to “crowd out” investment. Two studies – one from Edward Gamber and John Seliski of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and another from former Obama Administration economist Ernie Tedeschi – both find that higher deficits and debt continue to put upward pressure on interest rates, as past research has indicated. Low pre-crisis interest rates, according to these studies, were the result of population aging, slower productivity growth, international demand for safe assets, and unconventional monetary policy. Recent further decreases are the result of collapsing economic activity and aggressive action from the Federal Reserve. Debt continues to push interest rates up in normal times, crowding out productive investment and thus slowing economic growth.

Myth #2: Like after World War II, it will be easy to reduce debt after the pandemic.

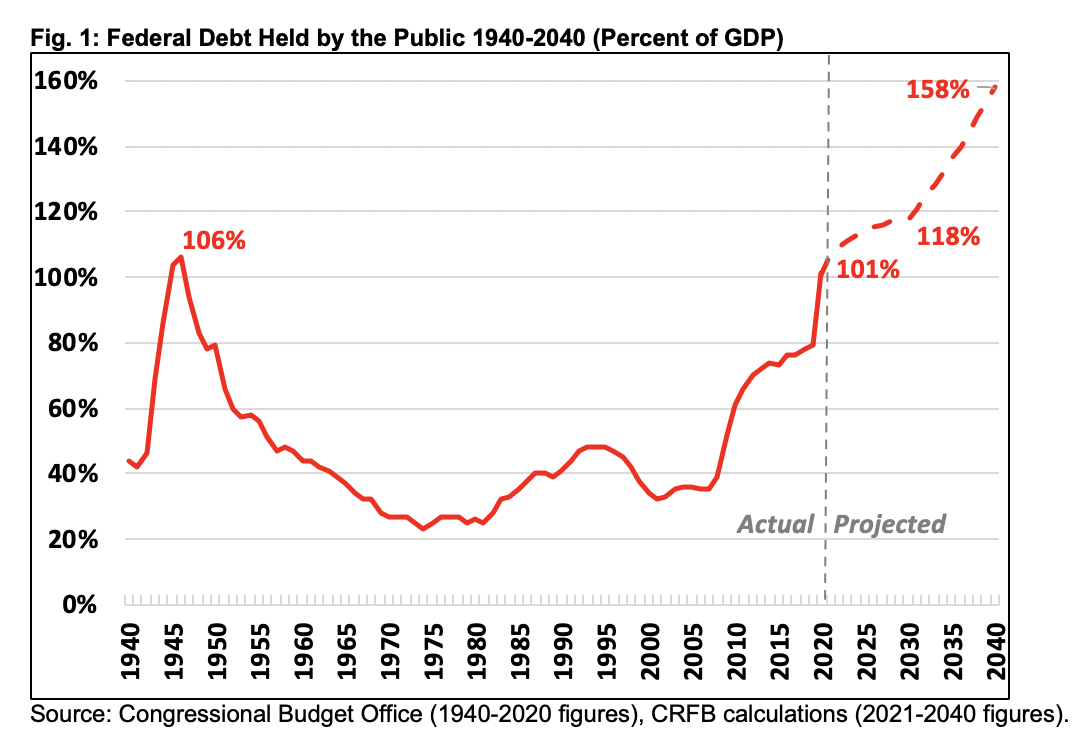

The last time debt exceeded the size of the economy was just after World War II, and it declined rapidly thereafter. After peaking at 106 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1946, debt- to-GDP fell in half within a decade and by two-thirds within two decades.

Unfortunately, there is no reason to expect a similar decline after the current crisis; rather, projections suggest debt will continue to grow rapidly as a share of GDP. Two factors allowed the United States to quickly shed its massive debt burden after World War II: near-balanced budgets and rapid economic growth. Thanks to years of roughly balanced budgets, nominal debt held by the public declined from $242 billion to $222 billion between 1946 and 1956 and did not exceed 1946 levels until 1962. Over that same period, nominal GDP grew by an average of more than 6 percent per year. The combination of stable nominal debt and rapid economic growth helped the debt-to-GDP ratio to decline rapidly.

By comparison, the United States entered the current crisis facing structural deficits over $1 trillion (almost 5 percent of GDP) per year – deficits that were slated to grow as health costs rose and the share of retirees grew over the next two decades. Assuming no further legislation is enacted to combat the crisis or otherwise increase borrowing, we estimate debt will grow by $14 trillion between the end of 2021 and 2030 – rising from 108 percent of GDP to 118 percent under current law. By 2040, we project debt will rise by another $33 trillion to 158 percent of GDP.

As Urban Institute fellow and Committee for a Responsible Federal board member Gene Steuerle recently explained, the future growth of borrowing is largely driven by permanent tax and spending laws that are effectively on autopilot and would require affirmative action to reverse.

The country cannot count on the same kind of rapid economic growth that occurred in the years following World War II. The Congressional Budget Office projects post-COVID nominal GDP will grow by 4.4 percent per year between 2021 and 2030 – the combination of 2 percent annual inflation and 2.4 percent real annual growth. Structural growth is significantly lower, likely below 2 percent, and boosted by projections of a slow but steady economic recovery. While a further increase in economic growth is possible, our research and others have shown that a structural growth rate above 3 percent is highly unlikely in light of the aging population. It would also be very difficult to inflate away the debt, as a large share of the budget and tax code is implicitly or explicitly linked to inflation.

In order to reduce debt-to-GDP in half by 2031, mirroring what happened after World War II, policymakers would need identify over $20 trillion (61 percent of GDP) of deficit reduction over ten years. Alternatively, real GDP growth would need to be sustained at nearly 6 percent for a decade or inflation would need to be about 12 percent.

Myth #3: The Federal Reserve can keep buying our debt without consequences.

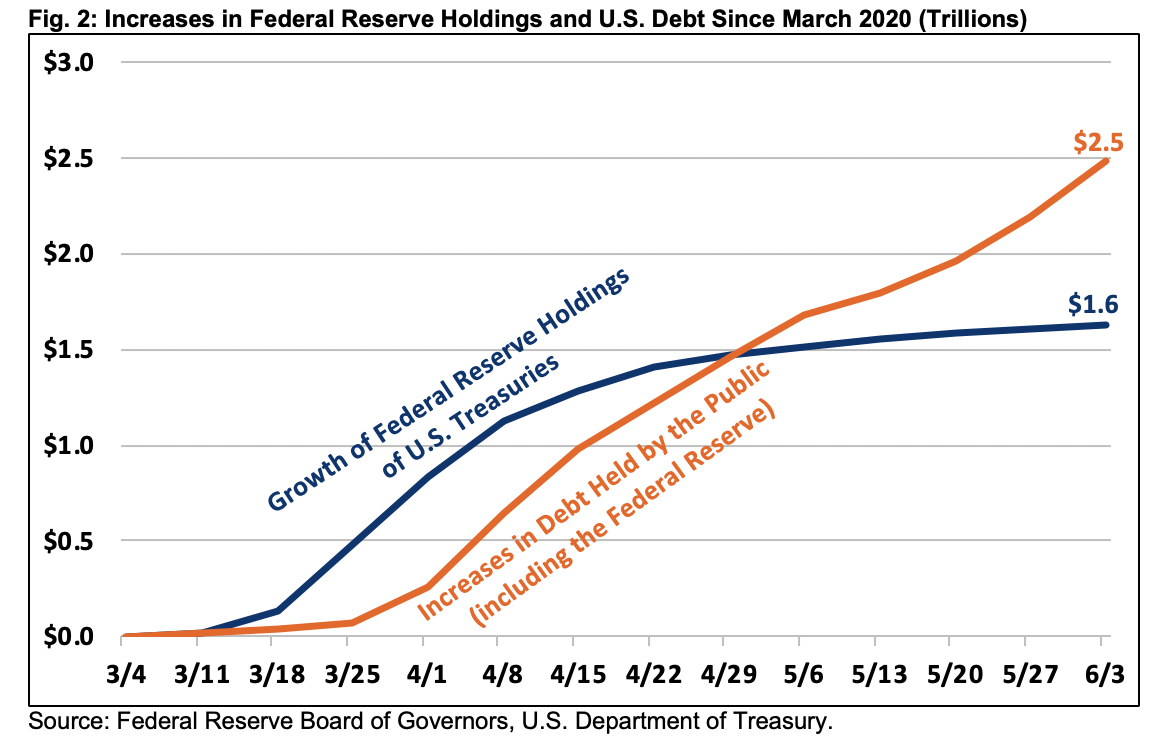

As part of its efforts to promote economic and financial stability, the Federal Reserve has purchased over $1.6 trillion of federal debt since March – enough to cover all the debt issued through April and two-thirds of new debt issued through May. While the Federal Reserve does not purchase debt directly from the U.S. Treasury, the fact that it pays for this debt by essentially adding to the money supply has led some to conclude that the central bank is effectively “monetizing” the debt. Whether this is in fact monetization, more traditional quantitative easing, efforts to maintain liquidity, or something else, these purchases have likely made it easier for the federal government to issue more debt at a very low interest rate.

However, it is unlikely the Federal Reserve would or could continue purchasing debt at its recent pace, since efforts to do so could have serious adverse consequences.

As the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell recently noted, the Federal Reserve’s “balance sheet can’t go to infinity” – meaning it cannot buy rising government debt forever. And importantly, the central bank has already significantly slowed its purchases from $75 billion per day in March to just $4 billion per day last week.

Moreover, while bond purchases can lower interest rates and boost output when the economy is depressed, they could actually push up interest rates or inflation when the economy is strong. Debt monetization during periods of full employment could force the Federal Reserve to choose between paying high interest rates on its reserves (which would reverberate through the economy) or paying low or no interest rates and allowing high levels of inflation to emerge. And to the extent that both interest rates and inflation do remain low, research suggests this scenario could permanently slow economic growth by allowing unproductive firms to stay in business, increasing market concentration, encouraging investments with poor returns, promoting excessive risk-taking, or creating new asset bubbles.

In the worst case, if the Federal Reserve were to become a pure extension of fiscal policy, the central bank’s credibility to ensure stable prices could erode and – in concert with high and rising deficits – spur rapid inflation.

What's Next

-

Image

-

-

Image