President Biden's Full FY 2022 Budget

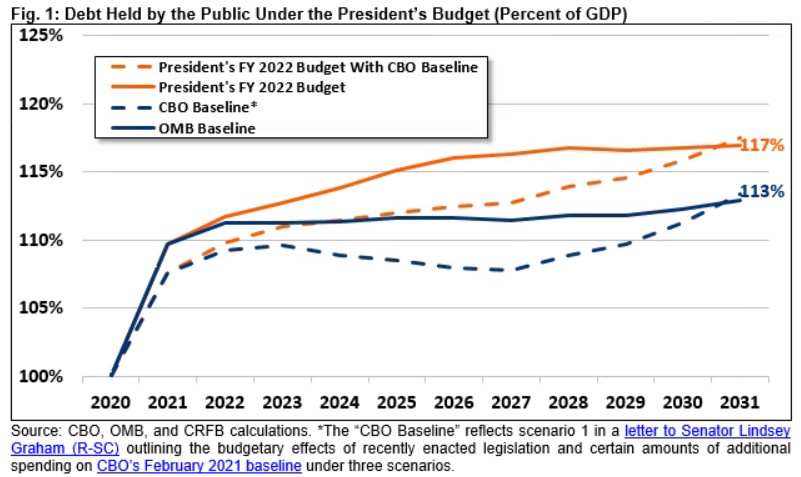

The Biden Administration today released its first full budget, laying out its proposals for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 and the subsequent decade. The budget proposes significant increases in spending, revenue, and borrowing over the next ten years. Under the plan, the Administration estimates debt would grow to 117 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by the end of FY 2031, compared to the 113 percent of GDP under the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) baseline.

Based on the administration’s estimates, our analysis shows that under the budget:

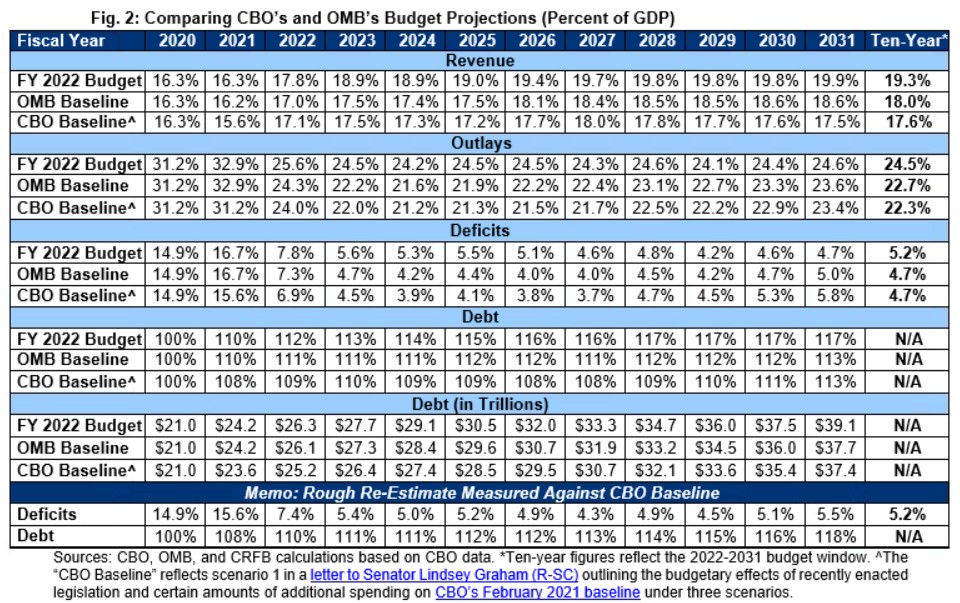

- Debt would rise from 100 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2020 and a record 110 percent at the end of 2021 to 114 percent by 2024 and 117 percent by the end of FY 2031. In nominal dollars, debt would grow by $17 trillion, from $22 trillion today to over $39 trillion by the end of FY 2031.

- Budget deficits would total $14.5 trillion (5.1 percent of GDP) over the next decade. Annual deficits would fall from $1.8 trillion (7.8 percent of GDP) in FY 2022 to $1.3 trillion (4.6 percent of GDP) in 2027 before rising to $1.6 trillion (4.7 percent of GDP) by 2031.

- Spending and revenue would total 24.5 and 19.3 percent of GDP over the coming decade, respectively. This would be higher than the administration’s baseline projection of 22.7 and 18.0 percent of GDP, respectively, and far above both the 50-year averages of 20.6 and 17.3 percent of GDP.

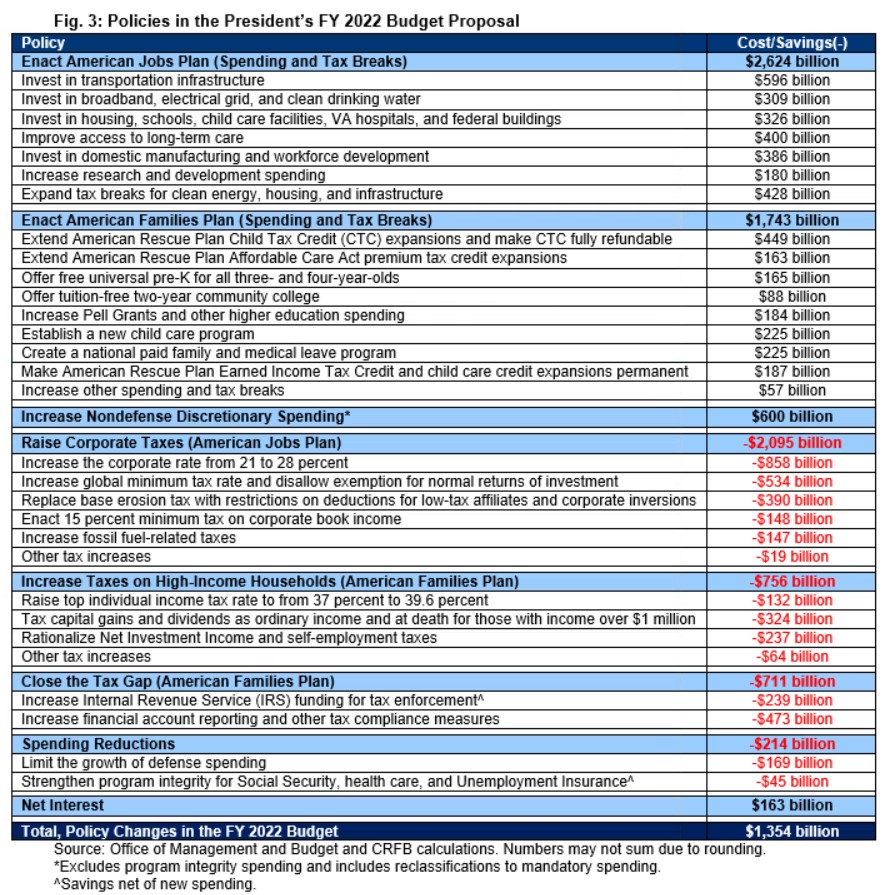

- Deficits would be nearly $1.4 trillion above current law over the next decade. This includes $5 trillion in new spending and tax breaks reflected in the American Jobs Plan, the American Families Plan, and nondefense discretionary spending and $163 billion in net interest costs, partially offset by $3.8 trillion of tax increases and spending reductions. The budget would start reducing the deficit in 2030 and beyond.

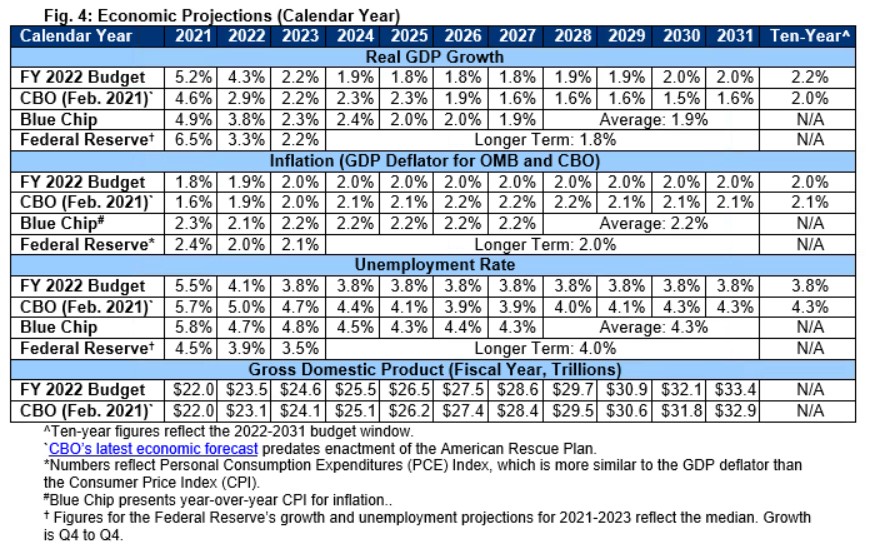

- Economic assumptions underlying the budget are modestly more optimistic than independent forecasts but do not appear to affect budget outcomes much. For example, the budget projects real GDP growth would average 1.9 percent in the second half of the decade, compared to CBO’s projection of 1.6 percent and the Federal Reserve’s central prediction of 1.8 percent.

We are pleased that President Biden has put forward important details of his budget plan, that his economic assumptions are reasonable, and that he is proposing to offset new costs over time while modestly reducing long-term deficits. However, the budget adds too much to already record-level debt over the next decade and does far too little to address rising structural deficits over the long term.

Debt, Deficits, Revenue, and Spending in the President’s Budget

According to its own estimates, debt under the President’s budget would grow substantially over the next decade. Federal debt held by the public would rise from 100 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2020 and a record 110 percent of GDP in 2021 to 114 percent of GDP by 2024 and 117 percent of GDP by the end of 2031. In nominal dollars, debt would grow by $17.1 trillion through the end of FY 2031, from $22.0 trillion today to $39.1 trillion in FY 2031.

OMB projects debt to reach 113 percent of GDP by 2031 under current law, which is similar to what the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects. Debt in the budget would fall below baseline levels by 2038 and would grow at a slower rate thereafter.

Annual deficits, according to the budget, would fall in the near term as COVID relief expires but then grow as a result of the President’s spending proposals and underlying pressure from health, retirement, and interest costs. Specifically, the deficit would fall from $3.7 trillion in FY 2021 to $1.8 trillion in 2022 and $1.3 trillion by 2027 before rising to $1.6 trillion by 2031. As a share of GDP, the deficit would fall from 16.7 percent of GDP in FY 2021 to a low of 4.2 percent of GDP in 2029 before growing to 4.7 percent of GDP by 2031.

Over the decade, deficits would be 0.5 percent of GDP ($1.4 trillion) higher than under OMB’s baseline. However, by 2030, the budget would begin reducing deficits, including by $93 billion (0.3 percent of GDP) in 2031 and by about $300 billion (roughly 0.6 to 0.7 percent of GDP) in 2041.

The large deficits in the President’s budget reflect both large structural imbalances under current law and, over the first eight years, the fact that President Biden’s proposed new spending will exceed proposed revenue offsets.

Under the budget, spending would average 24.5 percent of GDP over the 2022-2031 budget window, 1.8 percent of GDP higher than the 22.7 percent of GDP average estimated in OMB’s baseline. Average spending would not only exceed 50-year average of 20.6 percent of GDP, but would also exceed the post-WWII and pre-COVID record of 24.4 percent of GDP set in FY 2009.

Meanwhile, revenue would average 19.3 percent of GDP over the next decade – 1.3 percent of GDP higher than the 18.0 percent of GDP average estimated under OMB’s baseline – and reach 19.9 percent of GDP by 2031. This would far exceed the 50-year average of 17.3 percent of GDP and come close to the post-WWII record of 20.0 percent of GDP set in FY 2000.

Proposals in the President’s Budget

The President’s budget proposes about $5 trillion of new spending and tax breaks, reflecting the previously proposed American Jobs Plan, American Families Plan, and nondefense discretionary spending increases. These provisions would be partially offset with nearly $3.6 trillion of new revenue and over $200 billion of budget cuts and savings. The budget would also add $163 billion of interest costs. We will detail the proposals more thoroughly in a future analysis.

Economic Assumptions in the President’s Budget

A budget’s economic assumptions underlie every estimate it provides. Manageable debt levels and smart spending and tax policies can promote economic growth, while strong economic growth can improve the budget outlook. Overall, the economic assumptions used in the President’s budget are reasonable but somewhat more optimistic than consensus levels and appear to have little impact on overall budget estimates.

OMB projects real (inflation-adjusted) GDP growth of 5.2 percent in calendar year (CY) 2021, 4.3 percent in 2022, and 2.2 percent in 2023 as the economy recovers and continues to benefit from recent stimulus measures. In the second half of the decade, OMB projects average real GDP growth of about 1.9 percent per year.

The budget’s growth assumptions of 2.2 percent per year over the decade and 1.9 percent per year in the second half of the decade are somewhat higher than CBO’s projections of 2.0 and 1.6 percent and the Federal Reserve’s 2.0 and 1.8 percent estimates. However, they are in line with the Blue Chip consensus, which is also 2.2 percent per year over the next decade and 1.9 percent per year in the longer term.

Throughout the President’s budget, unlike the economic projections made by CBO and other forecasters, the presumed economic impact of the President’s policies is embedded in OMB’s economic assumptions. There is good reason to believe public investments in areas like infrastructure, education, and childcare could boost economic output. However, the administration’s overall economic assumptions may prove on the optimistic side, in part because the positive economic effects of the budget’s proposals may be partially, fully, or more than offset by the economic impact of proposed tax increases and borrowing.1

OMB’s estimates are also similar to, though somewhat more optimistic than, consensus estimates when it comes to unemployment. The agency expects the unemployment rate to fall from 6.1 percent today to average 5.5 percent in CY 2021, 4.1 percent in 2022, and average 3.8 percent in the second half of the decade. By comparison, CBO expects the unemployment rate to settle at about 4.1 percent, the Federal Reserve predicts 4.0 percent, and the Blue Chip consensus predicts 4.3 percent.

In terms of interest rates, OMB expects the average rate on ten-year Treasury notes to rise from 1.2 percent this calendar year to 1.4 percent next year before rising further to 2.8 percent in 2031. CBO projected interest rates to reach 3.4 percent by 2031 (before incorporating the effects of the American Rescue Plan), while the Blue Chip consensus expects rates to rise to 2.5 percent.

In terms of inflation, OMB expects the GDP price index to grow by 1.8 percent this year and by an average of 2.0 percent over the subsequent decade. This is in line with CBO’s (pre-ARP) estimate of 2.1 percent and the Blue Chip estimate of 2.2 percent for growth in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), as well as the Federal Reserve’s forecast of 2.0 percent long-term growth in the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index.

In all likelihood, OMB’s near-term inflation expectations are actually substantially underestimated. Through April, both the CPI and PCE indexes have already grown as much relative to 2020 as the budget expects over the entire year. Even without further price growth, which is highly likely over the next eight months, inflation would exceed OMB’s projections.

Overall, OMB’s relatively high growth and low interest rate assumptions, compared to CBO’s, should tend to reduce the expected debt-to-GDP ratio. However, OMB’s low inflation assumptions also push in the other direction. Overall, we expect CBO’s re-estimate of the President’s budget will not differ much based on macroeconomic assumptions.

Conclusion

While we are pleased that President Biden has put forward a comprehensive proposal to offset new spending priorities over time and reduce deficits in future decades, the budget adds too much to the debt over the next ten years and does too little to address high and rising debt over the long term.

Proposed revenue in the President’s budget deserves serious consideration, and policymakers who object to the President’s proposal should put forth alternatives. However, the $3.8 trillion of offsets in the budget will only cover around three-quarters of the cost of new spending and tax breaks over a decade, resulting in nearly $1.4 trillion of additional debt.

Rather than putting the debt on a stable and then downward path relative to the economy, the President’s budget would blow past the prior record and increase debt levels to 117 percent of GDP by 2031.

The President must take the lead in pushing for incremental or comprehensive legislation to not only pay for his agenda but also lower health care costs, secure trust funds, control existing spending, and raise new revenue to help close structural deficits.

The national debt is on an unsustainable path and headed to uncharted territory. Policymakers should work together to correct course.

1 For example, the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) estimated that the American Families Plan and the American Jobs Plan, including revenue provisions, would slow economic growth by more than 0.1 percent per year. Moody’s Analytics estimated that the plans would boost growth by 0.3 percent per year. Other estimates have found very small positive or very small negative effects on GDP.

What's Next

-

-

Image

-

Image