Fixing Medicare Physician Payments

Medicare pays physicians in traditional fee-for-service through the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS), which sets specific payment amounts for more than 10,000 procedures, tests, and imaging codes representing services provided to beneficiaries. The PFS is responsible for roughly 17% of Medicare FFS spending.1 Medicare is already among the largest and fastest-growing programs in the federal budget ($910 billion in 2024).

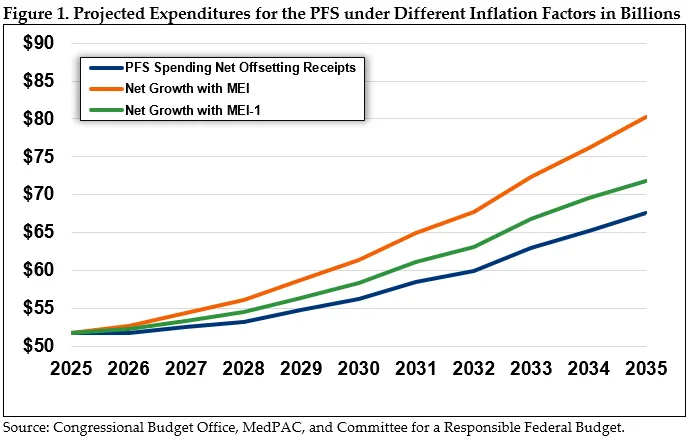

The law limits how much PFS can grow from year to year, but Congress is weighing proposals to make regular, annual updates to physician payments. If updates were indexed to a rate of Medicare inflation, they could increase federal spending by up to $65 billion while also increasing beneficiaries’ premiums and cost sharing.

Reforms to the PFS would improve payment accuracy and limit the distortions in the value of different services. This in turn could help to moderate and partially offset long-term cost growth, including when it comes to the specifics of any future payment increases.

In this brief, we discuss several options to reform and improve the PFS, including by better accounting for physicians’ efficiency gains in performing procedures and using technology, systematically revaluing codes as their relative values change, and improving tracking of advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners. These options, though modest in savings, would improve the fairness of Medicare physician payments as well as payments in other parts of the health care system, including commercial payers that frequently use Medicare’s fee schedules as a basis for rate setting. Perhaps more significantly, they would help Congress reduce the costs of any PFS legislation and ensure that policymakers avoid entrenching distorted payments for years to come.

Over the next decade (2026-2035), changes to the PFS outlined below could help:

- Avoid or moderate up to $65 billion in Medicare spending

- Avoid or moderate up to $30 billion in premium and cost-sharing increases for Medicare beneficiaries

* * * * *

The Health Savers Initiative is a project of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Arnold Ventures, and West Health, which works to identify bold and concrete policy options to make health care more affordable for the federal government, businesses, and households. This brief presents an option meant to be just one of many, but it incorporates specifications and savings estimates so policymakers can weigh costs and benefits, and gain a better understanding of whatever health savings policies they choose to pursue.

How Medicare Pays for Physician Services

The PFS articulates payments for physicians and other health care professionals for office visits and some procedures and tests provided under Medicare Part B. Under the PFS, clinicians submit treatment codes to describe the services they provide and are later reimbursed by Medicare for each service rendered. The PFS sets reimbursement rates for physicians as well as other clinicians, including advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners. Medicare Advantage (MA) plans do not have to use the PFS to develop payment rates for clinicians, but MA plans, some state Medicaid programs, and other commercial payers often use the PFS as a basis for rate-setting. For example, a private insurer may use the PFS’ payment rates to set ratios on their own fee schedule between primary and specialty care. As such, the rates set by the PFS have implications for the entire health system.

To calculate the amount of payment for each code, the fee schedule uses a formula to pay physicians more for services that are more time- and resource-intensive to provide. The formula consists of several components. First, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) assigns relative value units (RVUs) to each code based on the resources typically needed to deliver care. There are three categories of RVUs: work RVUs reflect physicians’ time and intensity of medical decision-making and provision of care; practice expense RVUs account for other direct and indirect costs of running a practice; and malpractice RVUs capture risk factors and costs from malpractice insurance. RVUs are also adjusted for geographic factors. CMS then multiplies the total RVUs by a fixed dollar amount called the “conversion factor” to get the total dollar amount for a treatment code. CMS is responsible for updating all the relative values of different services in the fee schedule. To do so, CMS draws heavily from recommendations from the American Medical Association (AMA)’s Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC).

Since 1989, CMS’s changes to individual PFS codes have been required to be budget neutral year over year, meaning any significant increase in spending driven by the creation of new codes or increased payment for existing codes must be offset by decreases to relative values, and thus payment, elsewhere in the fee schedule.2

The budget neutrality requirement makes annual federal costs more predictable than they would be without it. With Medicare costs growing faster than the national economy, budget neutrality is a key mechanism to prevent excessive spending growth in the federal budget.3

Other statutory provisions increase rates across the board. Payment rates increase in the aggregate for all services (rather than for specific services) based on a percentage set in statute. For example, annual statutory increases to physician rates were set at 0.5% for the years 2016 to 2018 before dropping to 0.25% in 2019. The statute had no increases scheduled from 2020 to 2025. However, during that time, Congress regularly intervened to increase PFS rates. Between 2021 and 2026 Congress increased payment rates each year except for 2025 by 2.5% to 3.75% in each year (the increases were not cumulative).4 According to our analysis of CBO estimates of each payment increase, these changes increased total spending by about $10 billion over that time period.

Rather than rely on the statute’s modest increase schedule and ad hoc Congressional increases, some stakeholders have called for statutory changes that would index PFS rates to an inflation factor. For example, the CMS Office of the Actuary noted that the low, scheduled payment updates have not yet resulted in limited access, but Congress is likely to increase payment rates in the future to help ensure Medicare beneficiaries continue to have access to care.5

The Medicare Payment and Access Committee (MedPAC) recently recommended that Congress index the PFS to a growth rate that reflects a portion of the rate of growth of Medicare costs.6 Specifically, they suggested Congress consider indexing PFS rates to rise annually at the rate of the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) minus one percentage point.7 However, just as weakening budget neutrality would increase federal spending significantly, so too would indexing the PFS.

Figure 1 estimates federal spending forecasts given different PFS policies over the next ten years. Specifically, we estimate that indexing the PFS to MEI would increase federal costs by approximately $65 billion over the baseline, and MEI-1 would cost an additional $25 billion from 2026 to 2035.

Recent Efforts to Change the PFS

When Congress established the fee schedule in 1989, they hoped to control growth in Medicare spending and fix pricing distortions under the prior system. However, vulnerabilities have emerged within the now more than 35-year-old system through changes in technology, care delivery, and the cost of practicing medicine. In recent years, many different stakeholders have criticized the fee schedule. Some practitioners say payment rates are unpredictable and do not adequately cover the cost of care. Others note that, unlike other Medicare payment systems, there is no mechanism to update rates to reflect inflation beyond a $20 million budget neutrality adjustment, if warranted. Many criticize its undervaluation of time-based services (i.e., primary care and cognitive services), and some highlight its inability to reflect new technologies and innovation in care delivery.

In response to stakeholder criticism, Congress has taken a bipartisan interest in many of these issues. The House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health held a hearing examining these issues in October 2023.8 Since then, Senators have formed a Medicare payment reform workgroup, held hearings, published a Request for Information (RFI) and a white paper.9,10,11,12,13 A number of bipartisan bills were introduced in the 118th and the 119th Congress. Several bills propose reform to the fee schedule’s conversion factor or budget neutrality requirement, including the Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act, the Provider Reimbursement Stability Act, and the Physician Fee Stabilization Act. The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 proposed a temporary boost to calendar year 2025 fee schedule payments (referred to as “Doc Fix”), while other bills, like the Pay PCPs Act of 2024, would enact more comprehensive reform.

More recently, CMS took action to address increasing PFS spending by finalizing a change to its rules that would automatically reduce payment on some codes for which clinicians have improved efficiency.14 CMS is also seeking better empirical data on the inputs that the RUC uses to recommend changes to valuations, citing concerns about the quality of the RUC’s survey data. These proposed changes are in line with the first option we recommend below. If finalized, this regulation could help improve the fairness of relative valuations.

Menu of Policy Options to Improve the PFS

We agree with lawmakers that it is time to modernize the fee schedule, and we urge them to do so in a fiscally responsible manner. This issue brief presents several policy and technical changes that could improve the fairness of the fee schedule while also helping to partially offset the costs of across-the-board increases.

Option 1: Capturing efficiency gains

The PFS is not designed to respond to clinicians getting more efficient through advances in technology, techniques, and clinical practice. For example, when a new test or procedure is added to the fee schedule, it may be valued relatively high because of the associated time, skill, and clinical decision-making. As physicians grow more comfortable with the new service, it becomes easier to provide, allowing the physician to perform more of these services per day. In theory, when efficiency gains reduce the amount of work or non-physician clinical labor needed for a service, the service’s work or practice expense RVUs should also decline. However, revaluation is an arduous process that rarely occurs, as described below.

The system leads to undervaluing primary care and overvaluing procedural services. Efficiency gains are more likely to occur in procedures, imaging, and tests compared to time-based office visits because the resources required for an office visit are generally fixed. The amount of time needed to intake a patient’s history, conduct a physical exam, and discuss treatment generally remains constant regardless of the physician’s experience. As a result, the relative payment rates for common time-based codes, such as E/M or behavioral health services, are “passively devalued” as the prices for procedures, imaging, and tests grow artificially high.15

One option to capture efficiency gains is to direct CMS to create an “efficiency adjustor” for services whose RVUs do not reflect gains in efficiency that occur. One paper recommended that CMS develop a “routine approach for decreasing” the relevant RVUs after a defined period of time. Once the new service reaches the designated time, CMS could apply the efficiency adjuster.16 Then, after CMS reviews the valuation, they could assign a more refined adjustment. It is important to include exceptions for services where efficiency gains are unlikely, such as E/M or cognitive services.

In addition to applying the efficiency adjustor to new services that have reached the designated time, the adjustor could also be applied to existing procedures, tests, or imaging services within the fee schedule that have experienced significant growth in volume and allowed charges for a period of time, such as three consecutive years. Such growth signals that the services or procedures associated with the code have become more routine and potentially less resource intensive. Tying these criteria to the efficiency adjustor is more practical than revaluing over 10,000 existing procedure, test, or imaging codes within the fee schedule.17

In line with this recommendation, in the calendar year 2026 PFS final rule, CMS implemented an “efficiency adjustment” to capture the increase in efficiency that clinicians gain as they get more experience with a procedure or service. CMS would apply a downward adjustment to the RVUs of many codes because the amount of physician time and the “work intensity decrease as the practitioner develops expertise in performing the specific service.”18 CMS proposed decreasing the relevant codes by the amount in the MEI productivity adjustment (codes based on time – such as evaluation and management codes – would be excluded from this adjustment). Because the adjustment would decrease the valuations of many services, it would result in a net increase to the conversion factor, but not federal savings.

Option 2: Expanding CMS’s work on misvalued codes

From the inception of the fee schedule’s relative value system, CMS has had to grapple with how to ensure each code’s values remain accurate in their relation to each other using clinically appropriate assumptions and transparent data. Beginning in 1989, Congress envisioned that CMS would conduct five-year reviews of each of the RVUs (work, practice expense, and malpractice).19 CMS conducted these reviews multiple times, but stakeholders expressed dissatisfaction with the process and urged CMS to develop a more rigorous process. MedPAC led the call for a more systematic approach. In its 2006 report to Congress, MedPAC explored the structural components of the fee schedule, including the issue of efficiency gains described above.20

In response to these concerns, CMS implemented two changes. First, the AMA/Specialty Society RUC began reviewing certain physician services, rather than only new codes. Second, in the Affordable Care Act, Congress directed the Secretary of HHS to focus on “potentially misvalued services” within several code categories. These include codes that have experienced the fastest growth or most substantial changes in practice expense as well as codes describing new technologies or services.21

In response to the statutory mandate, CMS began the misvalued code initiative, which it still employs today. CMS adjusts the relative value of codes deemed misvalued through its annual rulemaking process. In doing so, it is dependent on the recommendations from the AMA/Specialty Society’s RUC. In the calendar year 2026 PFS proposed rule, CMS reiterated concerns about using RUC survey data to support valuations, and sought input on better empirical data on the inputs used to revalue codes. CMS noted they need improved data to compensate for low-quality survey data that the RUC uses to recommend changes to valuations.22

The agency estimates that it has reviewed more than 1,700 potentially misvalued codes, and, excluding never before reviewed codes, they estimate it takes approximately 17 years between reviews of each code.23 The process has drawn significant scrutiny over time for failing to fairly value office visits as opposed to procedures, and for focusing too much on increasing the value of undervalued codes rather than reducing the value of existing overvalued codes.24

Despite these efforts, CMS can do more to actively and transparently manage the PFS values. Congress should establish a more automated and adequately resourced approach to the misvalued initiative. In addition to its routine reviews, CMS could annually publish codes that grew the fastest over a period of time (e.g., three consecutive years) in billing volume or other factors.25 If more than five years elapse since the service’s resource inputs (work or PE) were last reviewed, then CMS would be required to immediately propose an updated service valuation. Congress could also specify that if the code were misvalued by more than a certain percentage, CMS would make an automatic payment adjustment until the service valuation review was complete.26 These options are designed to automate and target actions to address excessive spending on certain codes.

Option 3: Increase Transparency to Support Program Integrity through APP Billing Refinement

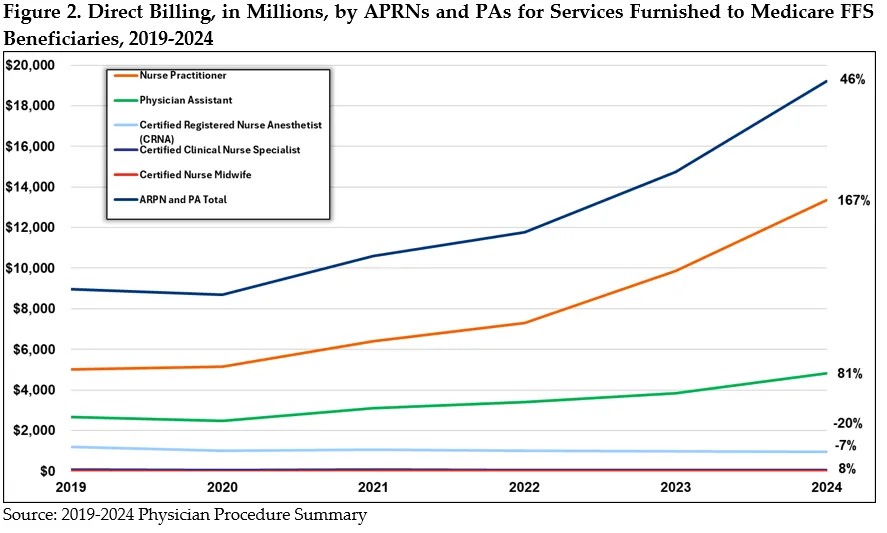

The role of Advanced Practice Providers (APPs) has expanded in recent years but the lack of information on their activities warrants further analysis to better understand the current state of care delivery.27 APPs include Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), Nurse Practitioners (NPs), and Physician Associates (PAs), and have been providing more care to Medicare beneficiaries over time. As shown in Figure 2, the amount APPs have billed directly (as opposed to under the supervision of a physician) increased by 46% between 2019-2024 from about $8.9 billion in 2019 to $19 billion in 2024.28

Information on APP’s specialties is unclear. These clinicians do not designate their specialty information on Medicare claims. Without further information on APP’s specialties, payment policy can be poorly targeted. For example, for some Medicare quality bonus payments, certain specialty providers receive an adjusted rate. Since some APPs are considered primary care providers, the qualifying payment adjustments may not be applied correctly.29

CMS could begin to require APPs to list a second specialty in the Medicare enrollment systems and annually update that information. Additional specialty-level detail on APPs will flow through to claims databases, increasing transparency and facilitating research on the specialty areas in which APPs practice. MedPAC previously recommended this, calling for the Secretary to refine Medicare’s specialty designations for APRNs and PAs. MedPAC noted that the supply of NPs and PAs continues to increase, with many of these practitioners moving outside of primary care. As noted by the Commission, improved accounting of APP service provision to Medicare beneficiaries will facilitate improved study and resource allocation within the system.30

CMS’s “incident to” billing rules also limit understanding of the care furnished by APPs to Medicare beneficiaries. Services provided by the APP may be billed to Medicare under the supervising physician’s identification number (the National Provider Identifier (NPI)), appearing in claims data as if the physician furnished the care and prompting reimbursement at the full PFS payment amount. When billed independently – or not under the physician’s NPI – services performed by APPs are reimbursed at a rate of 85% of the PFS rate for physicians. In contrast, when the same APPs bill “incident to,” the rate is 100% of the physician rate. For this reason, the “incident to” billing model incentivizes physicians to obtain higher reimbursement at lower costs by shifting patient follow-up care to non-physician practitioners. “Incident to” billing increases costs to the Medicare program and impedes accurate data collection on service provision.

Under CMS’s “incident to” billing regulations, once certain conditions are met, the APP may bill the service as if the physician rendered the visit, receiving 100% of the Medicare reimbursable amount.31 While delivering care under an “incident to” billing model allows practices to see more patients, improve workflow and caseload management, it masks APP service provision to Medicare beneficiaries.32 Organizations representing APPs support action to improve the transparency of services. They suggest that under “incident to,” their services are “invisible” and may undermine value-based care principles and program integrity by making it hard for oversight entities to identify the person responsible for overpayments, for example.33,34,35,36

MedPAC recommended Congress eliminate “incident to” billing and require APPs to submit claims under their own NPIs rather than the supervising physician’s. As part of their recommendation, the Commission outlined “substantial benefits” of billing reform including budgetary savings, estimating several years ago that eliminating “incident to” could reduce program spending by $50-$250 million in the first year and accumulate to a $1-5 billion spending reduction over the first five years.37 The potential cost savings of “incident to” reform are likely much greater over time as medical groups continue to integrate APPs into their practices.38

Congress could direct the Secretary to eliminate “incident to” billing models, giving sufficient notice for clinicians to prepare for such a change. These rules were established more than 50 years ago and should be reconsidered.39 At minimum, CMS should establish a claims-tracking requirement to identify when services are furnished by APPs under “incident to” rules. Eliminating “incident to” and requiring APPs to direct bill will accurately reflect the clinician furnishing care in Medicare claims data, improve transparency, program integrity, and align reimbursement with current care delivery patterns.

Conclusion

Congress faces significant pressure to increase the annual updates to the PFS, which would lead to greater federal spending, larger deficits, and higher premiums and cost sharing.

This paper outlines ways to avoid, moderate, and/or partially offset such costs and ensure any increases do not perpetuate mis-valuations. Solutions discussed in this paper – along with CMS’s recent final rule applying an efficiency adjustment – can also help to improve payment accuracy in the fee schedule. These options are increasingly important as Congress considers approaches to update physician pay, like indexing the PFS to an inflation factor like MEI. Doing so would increase federal spending by up to $65 billion over the baseline.

A responsible payment system for Medicare physician and practitioner services is critical to ensuring a robust health care workforce and beneficiaries’ access to needed services. However, the system has failed to evolve with changes in the way that clinicians provide care. As a result, the PFS currently incorporates distorted incentives and does not provide the predictability health professionals nationwide deserve. The menu of options presented in this brief are modest in savings but are meaningful ways to help Congress reduce the costs of physician fee schedule-related legislation and improve the fee schedule in the process.

1 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), “June 2025 Report to the Congress, Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Chapter One: Reforming Physician Fee Schedule Updates and Improving the Accuracy of Relative Payment Rates,” June 12, 2025, Page 9, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Jun25_Ch1_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf. Elsewhere in this paper, generally we use Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data.

2 Significant increases are defined as those projected to cost more than $20 million in a year. 42 U.S.C. §1395w–4(c)(2)(B)(II) or section 1848(c)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of Social Security Act (SSA). As one example of the effects of budget neutrality, a 2021 update to office/outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes would have cost $11 billion in one year alone without an offsetting decrease in the conversion factor. See CMS, “Medicare Program; CY 2021 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies,” (85 FR 84472), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 28, 2020, See “Utilization Estimates for E/M Add-on Code,” Page 84572, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/12/28/2020-26815/medicare-program-cy-2021-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other-changes-to-part.

3 Medicare Board of Trustees, “2024 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), May 6, 2024, Page 8, https://www.cms.gov/oact/tr/2024.

4 MedPAC, “June 2025 Report to the Congress, Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Chapter One: Reforming Physician Fee Schedule Updates and Improving the Accuracy of Relative Payment Rates,” June 12, 2025, See Fig. 1-1, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Jun25_Ch1_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf.

5 CMS Office of the Actuary, Memo from John D. Shatto and M. Kent Clemens, “Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Payment Updates to Medicare Providers,” June 18, 2025, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/illustrative-alternative-scenario-2025.pdf.

6 CMS, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY2026 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule.”

7 Id.

8 House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health, "What’s the Prognosis?: Examining Medicare Proposals to Improve Patient Access to Care & Minimize Red Tape for Doctors," U.S. House of Representatives, October 19, 2023, https://energycommerce.house.gov/events/health-legislative-hearing-what-s-the-prognosis-examining-medicare-proposals-to-improve-patient-access-to-care-and-minimize-red-tape-for-doctors.

9 Senator Marsha Blackburn, “Blackburn, Thune, Barrasso, Stabenow, Warner, Cortez Masto Announce Formation Of Medicare Payment Reform Working Group,” U.S. Senate, February 9, 2024, https://www.blackburn.senate.gov/2024/2/issues/health-care/blackburn-thune-barrasso-stabenow-warner-cortez-masto-announce-formation-of-medicare-payment-reform-working-group.

10 U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget Committee Hearing, “Reducing Paperwork, Cutting Costs: Alleviating Administrative Burdens in Health Care,” U.S. House of Representatives, May 8, 2024, https://www.budget.senate.gov/hearings/reducing-paperwork-cutting-costs-alleviating-administrative-burdens-in-health-care.

11 U.S. Senate Committee on Finance Committee Hearing, “Bolstering Chronic Care through Medicare Physician Payment,” U.S. Senate, April 11, 2024, https://www.finance.senate.gov/hearings/bolstering-chronic-care-through-medicare-physician-payment.

12 Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, “Whitehouse and Cassidy Introduce Legislation, Release RFI on Primary Care Provider Payment Reform,” U.S. Senate, May 15, 2024, https://www.whitehouse.senate.gov/news/release/whitehouse-and-cassidy-introduce-legislation-release-rfi-on-primary-care-provider-payment-reform/.

13 U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, “Bolstering Chronic Care through Physician Payment: Current Challenges and Policy Options in Medicare Part B,” U.S. Senate, May 17, 2024. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/051723_phys_payment_cc_white_paper.pdf.

14 CMS, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY2026 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; and Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program,” Final Rule, CMS, October 31, 2025, https://insidehealthpolicy.com/sites/insidehealthpolicy.com/files/documents/2025/oct/he2025_2471a.pdf.

15 MedPAC, “Report to Congress: Chapter 3: Rebalancing Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule Toward Ambulatory Evaluation and Management Services,” CMS, June 1, 2018, Pages 65-66, https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-jun18_ch3_medpacreport_sec-pdf/.

16 Robert A. Berenson, Paul Ginsburg, Kevin J. Hayes, et al., et al., “Public comment to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule CY 2023 (CMS-1770-P),” Urban Institute, September 2, 2022, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/comment-letter-cy-2023-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule.

17 Analysis of the 2023 Restructured Berenson-Eggers Type of Service (RBETOS) subcategories listed in the 2023 Restructured BETOS Classification System Data File, https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/provider-service-classifications/restructured-betos-classification-system.

18 CMS, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY2026 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; and Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program,” Proposed Rule, 90 FR 32352, CMS, July 16, 2025, See Page 32401, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/07/16/2025-13271/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2026-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other.

19 42 U.S.C. § 1395w-4(c)(2)(B).

20 MedPAC, “Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy,” March 1, 2006, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/Mar06_EntireReport.pdf.

21 Section 3134(a) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148).

22 CMS, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY2026 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule, at 32399.

23 CMS, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY2026 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule, at 32400. Note that, for the 2025 misvalued code process, CMS only received five public nominations for a series of codes. CMS, Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2025 Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program; and Medicare Overpayments,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, December 9, 2024, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/12/09/2024-25382/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2025-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other.

24 Robert Berenson and Kevin J. Hayes, “The Road To Value Can’t Be Paved With A Broken Medicare Physician Fee Schedule,” Health Affairs, Vol. 43, No. 7, July 2024, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.00299.

25 For example: utilization by new specialty, unexplained geographic variances, site of service, etc.

26 When considering codes that may be appropriate for an automatic value adjustment, CMS should also look to recommendations from the HHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG). For example: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, “Additional Oversight of Remote Patient Monitoring in Medicare Is Needed,” OEI-02-23-00260, Department of Health and Human Services, September 24, 2024, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports/all/2024/additional-oversight-of-remote-patient-monitoring-in-medicare-is-needed/, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, “Medicare Part B Payments for Incident-To-Services,” OAS-25-01-003, Department of Health and Human Services, November 2024, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000901.asp.

27 Also referred to as non-physician providers (NPPs) including Physician assistants (PAs), Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs) including Nurse practitioners (NPs), Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNSs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), and Certified Nurse Midwives (CNMs) among other nonphysician practitioners. NPs, PAs and CNSs are paid at 15% of the PFS rate when independently billing. CRNAs and CNM are paid at 100%.

28 These figures do not account for services furnished by APPs and billed under a physician’s supervision, known as “incident to” rules.

29 Clarity on the care that APPs provide is important for other reasons as well. For example, in certain alternative payment models like Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), CMS tracks visits to providers to attribute patients to different providers. Without clear data, CMS may miss opportunities to assign patients to ACOs, thereby failing to capture information that could clarify the success or opportunities of a given ACO.

30 MedPAC, “June 2019 Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System,” June 14, 2019, Page 162, https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec-pdf/.

31 Once a patient has an established relationship and plan of care with a physician, an APP may furnish subsequent care (consistent with state scope of practice laws and reasonable and necessary requirements) under the supervision of a physician in the office suite.

32 Daniel F. Shay, “Using Medicare ‘Incident-To’ Rules,” Family Practice Management 22(2):15-17, March/April 2015, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/issues/2015/0300/p15.html.

33 Jonathan E. Sobel, “American Academy of PAs Responds to MedPAC’s Report on Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System,” American Academy of PAs, June 17, 2019, https://www.aapa.org/news-central/2019/06/american-academy-of-pas-responds-to-medpacs-report-on-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system/.

34 Maureen Stabile Beck, “Direct Versus “Incident to” Billing for Nurse Practitioners and Physician Associates: Understanding Billing Knowledge and Options,” The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, Volume 20, Issue 5, 104978, May 15, 2024, https://www.npjournal.org/article/S1555-4155(24)00054-0/abstract.

35 American Association of Nurse Practitioners, Letter to Seema Verma, “Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Innovation Center New Direction,” American Association of Nurse Practitioners, November 20, 2017, https://storage.aanp.org/www/documents/CMMI-Comments.pdf.

36 See for example, HHS Office of Inspector General, “Medicare Telehealth Services During the First Year of the Pandemic: Program Integrity Risks, OEI-02-20-00720, Department of Health and Human Services, September 2022, Page 15, https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/evaluation/2709/OEI-02-20-00720-Complete%20Report.pdf.

37 MedPAC, “June 2019 Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System,” June 14, 2019, Page 158, https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec-pdf/. Other researchers arrived at similar single-year estimates of fiscal savings. For example, one study found that if APPs billed direction, Medicare could save $270 million annually. John F. Mulcahy, Sadiq Y. Patel, Ateev Mehrotra, et al., “Quantifying Indirect Billing Within the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule,” JAMA Health Forum 2025; 6 (4): e250433. doi:10.1001, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2832435. An earlier study found that Medicare could save $194 million in 2018; Sadiq Y. Patel, Haiden A. Huskamp, Austin B. Frakt, et al., “Frequency of Indirect Billing to Medicare For Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Office Visits,” Health Affairs (Milwood), Volume 41, Number 6, 805-813, June 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01968?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed.

38 MedPAC, “June 2019 Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System,” June 14, 2019, Page 162, https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec-pdf/; Sadiq Y. Patel, Haiden A. Huskamp, Austin B. Frakt, et al., “Frequency of Indirect Billing to Medicare for Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Office Visits.” Health Affairs (Millwood) Volume 41, Number 6, 805-813, June 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01968?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed.

39 The OIG opened a workplan to examine Medicare Part B payments for “incident to” services with an expected report issue date in 2026. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, “Medicare Part B Payments for Incident to Services,” November 2024, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000901.asp.