Five Reasons to Pay for New Investments

Congress and the Administration are currently negotiating and developing legislation to invest in physical infrastructure, education, and other areas (along with new income support spending) based largely on the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan. Legislation is likely to proceed on two tracks, with most physical infrastructure spending passed in a bipartisan bill and remaining spending enacted on a partisan basis through reconciliation.

The federal budget currently skews heavily toward supporting consumption and spends almost $6 per senior for every $1 per child. Expanding public investments could improve generational fairness within the budget and help support stronger economic growth. But it is important that new spending – including new investment spending – be fully paid for with new revenue and/or spending reductions.

While some have argued the country should borrow for new investment spending, that view is wrong-headed in light of the current fiscal situation. New investments should be paid for at least the following five reasons:

- The country already faces large structural deficits and record debt

- Public investments will not pay for themselves

- Offsetting new investments is good for the economy

- Low interest rates do not make borrowing free or wise

- An “investment exemption” creates a slippery slope

Ultimately, if something is worth having, it is worth paying for. Public investments are valuable to households and businesses and important for economic growth. Policymakers should be willing to raise new revenue or reduce other spending in order to fund these important investments.

The Country Already Faces Large Structural Deficits and Record Debt

Businesses, households, and states all borrow to make investments, and there is a reasonable case that the federal government should as well. This justification disappears, however, when new borrowing comes on top of existing high and rising deficits and debt.

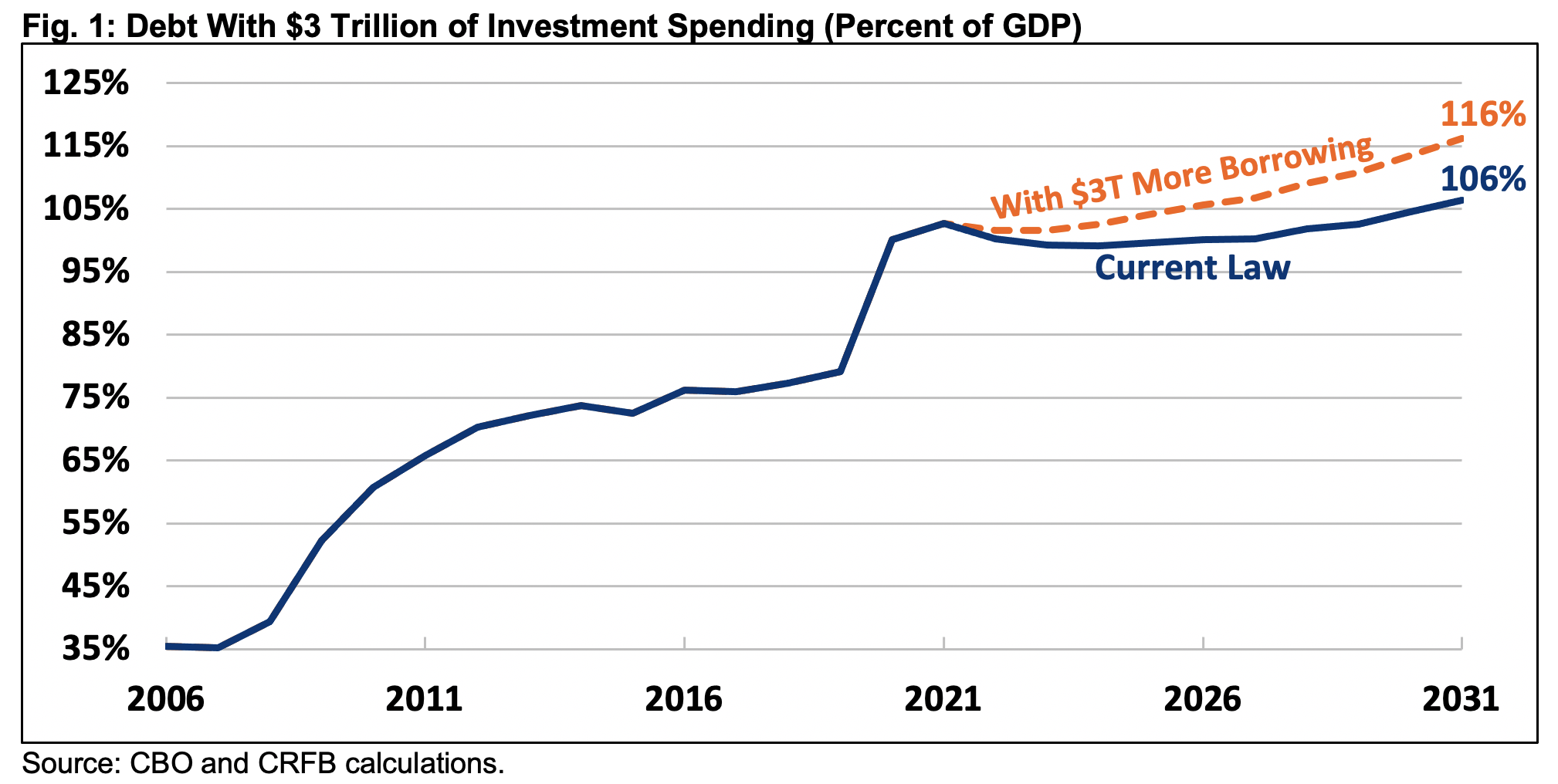

The federal government is slated to borrow nearly $13 trillion over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That would lift debt to a new record of 106.4 percent of economic output by 2031. Only about $4 trillion of this borrowing will be to fund public investments, meaning nearly $9 trillion of borrowing will cover the government’s operating budget, consumption-boosting transfers, and interest on the debt.1

Capital budgeting constructs allow governments to borrow for investments with a plan to pay back the funds over time (by covering interest and depreciation costs) and to keep their operating budgets in rough balance. Borrowing more for investment on a permanent basis with no plan to cover the costs over time on top of massive operating deficits would only make a bad fiscal situation worse. This is especially true for sustained permanent investment.

For example, if lawmakers increased investment spending by $3 trillion over ten years, it would result in record debt by 2027 instead of 2031 under current law, and debt would reach 116 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2031.

Public Investments Will Not Pay for Themselves

Smart public investments, whether in infrastructure, education, or research and development, can help to build productive capacity, boost output, and raise incomes, thus generating additional tax revenue. However, there are few if any situations where this new revenue would be large enough to fully cover the costs of new spending.

As with claims that tax cuts pay for themselves, assertions that new public investments will be self-financing are greatly exaggerated and don’t hold up to scrutiny.

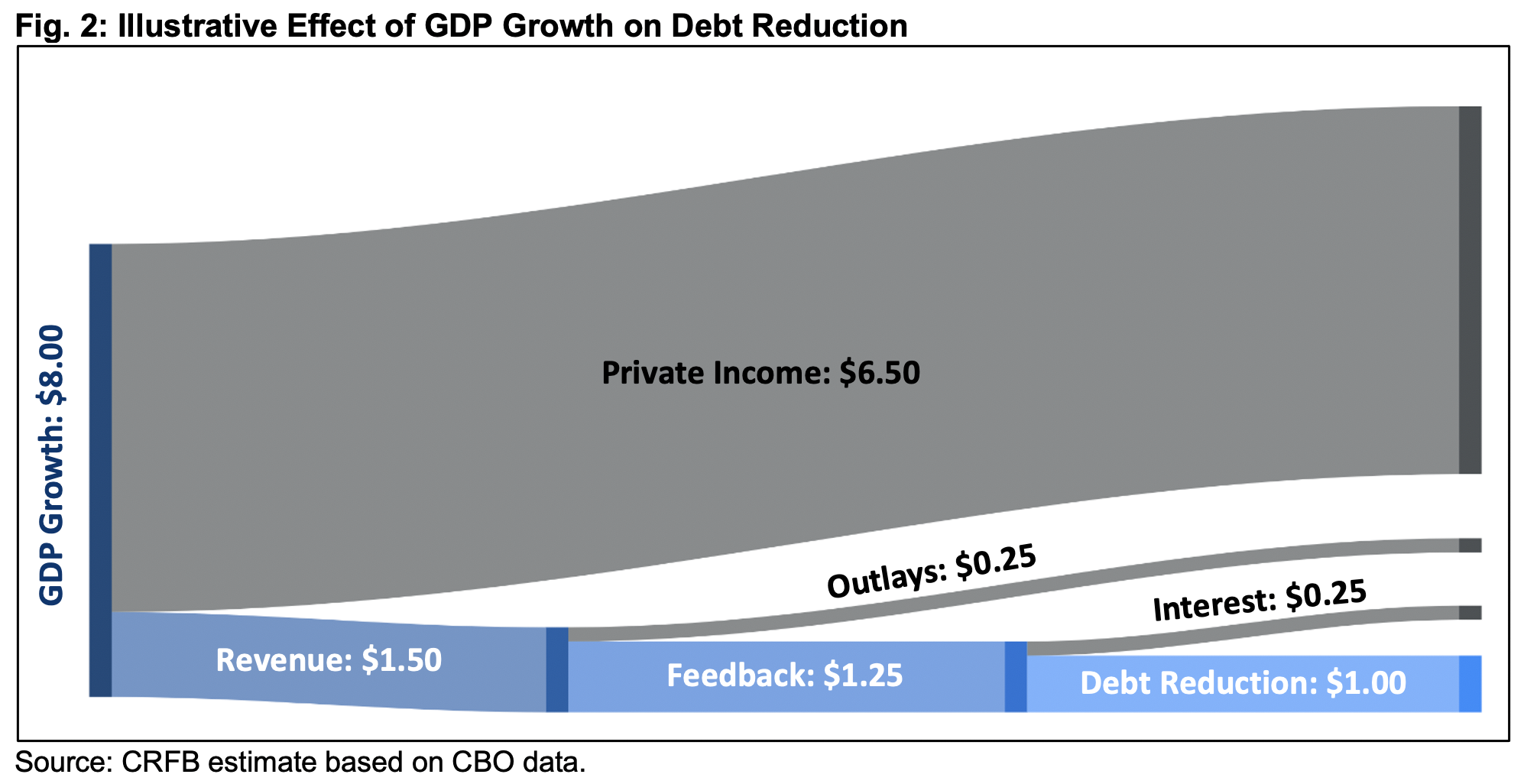

Because the federal government only captures a fraction of economic gains from taxes, public investments would have to generate massive economic returns to be self-financing. The government only taxes roughly 20 percent of income, meaning a project or policy would need to generate a 5-to-1 return simply to raise enough revenue to equal its costs.

Making it even more difficult, stronger economic growth (especially if debt-driven) also pushes up interest rates and the cost of some federal programs. Incorporating these effects, based rules of thumb produced by CBO, a new investment would need to produce returns of about 8-to-1. Very few investments would be able to generate such a massive return, and it is unlikely that any large-scale investment program would generate more than a fraction of this rate of return.

To be sure, a well-selected set of public investments could certainly be partially self-financing and pay for a faction of their costs. But it is unrealistic to assume new investments at any significant scale could fully pay for themselves.

Offsetting New Investments Is Good for the Economy

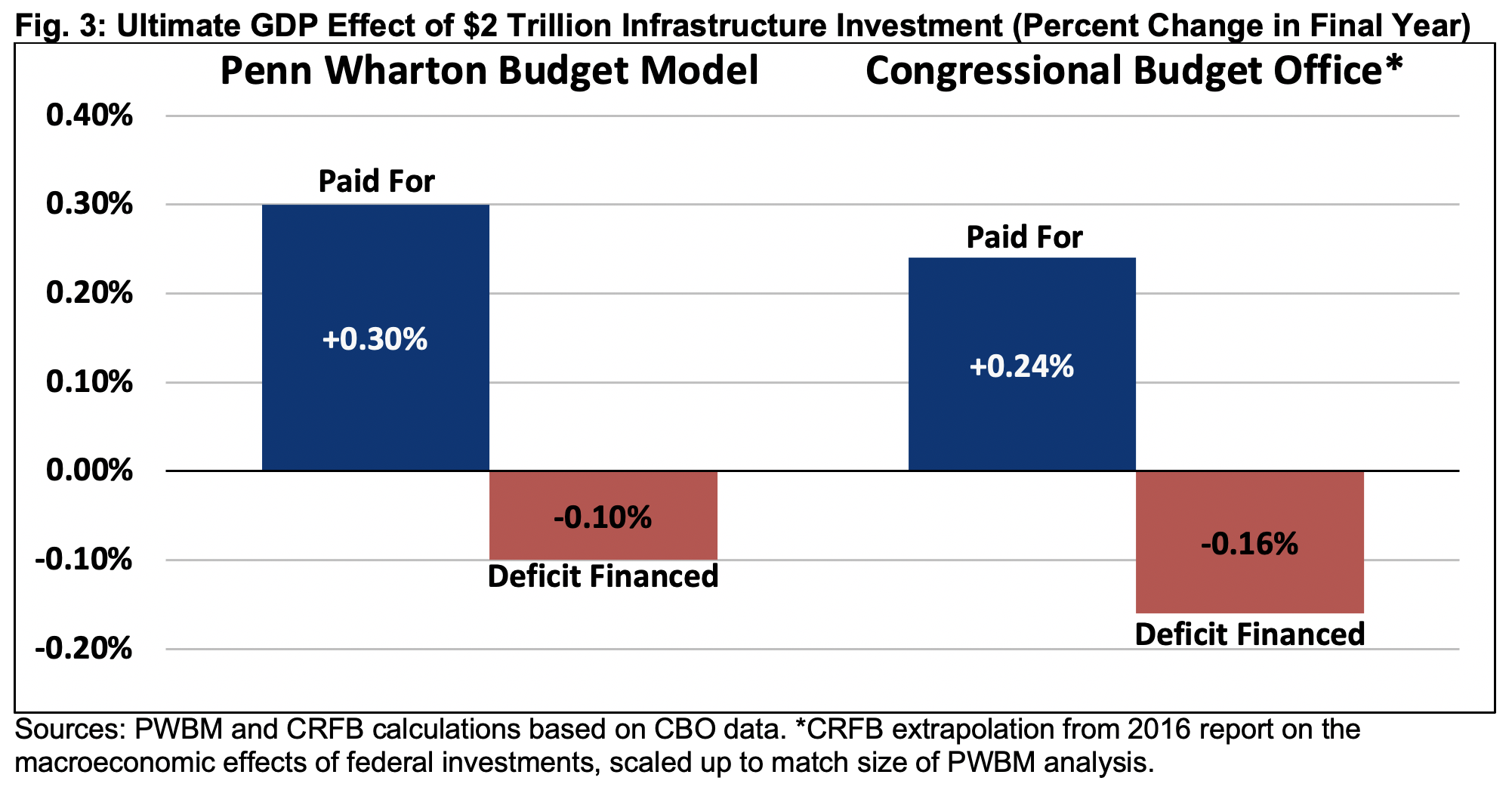

While borrowing made economic sense during the COVID crisis, adding more debt would do little to help the recovery and would undermine the long-term economic benefits of new investment. Independent estimators such as CBO and the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) have found that paid-for investments are more pro-growth than deficit-financed investments.

Thanks to $5.2 trillion of enacted net stimulus and support, along with vaccinations and re-openings, the economy appears to be on pace for a fast recovery, with increases in consumer demand outstripping supply. Further near-term borrowing will likely do little to boost output further and could lead to higher rates of inflation, faster tightening from the Federal Reserve, or other negative consequences.

Meanwhile, the negative long-term effects of new borrowing could temper or offset economic gains from new spending, with lower private investment reducing higher public investment.

Based on a 2016 CBO analysis, we estimate that a generic $2 trillion infrastructure investment package would ultimately grow the economy by 0.24 percent if paid for, but it would actually shrink the economy by 0.16 percent if deficit financed. More recently, PWBM estimated a generic $2 trillion package of paid-for infrastructure would boost output by 0.3 percent, while deficit-financed infrastructure would shrink it by 0.1 percent.

And importantly, the pay-fors themselves may be good economic policy. For example, user fees are fair and efficient, carbon taxes can mitigate climate change, cutting tax breaks can reduce distortions in the tax code, and Medicare reforms can lower health spending economy-wide.

Low Interest Rates Do Not Make Borrowing Free or Wise

Interest rates are currently near record lows and have been relatively low, by historical standards, for the last decade. Low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing but do not make it free.

While there are certainly benefits to financing high-return investments with low-interest debt, most of those advantages disappear without a strategy to ultimately pay back the principal. Low-rate bonds will eventually be rolled over at a higher interest rate, while investments themselves depreciate over time. As a result, the cost of the borrowing is likely to rise over time, while the benefits of the investment will wane.

CBO projects the ten-year bond yield will rise from an average of 1.6 percent in 2021 to 2.8 percent by 2026 and 3.5 percent by 2031. In a previous forecast, CBO projected rates would continue to rise to 4.2 percent by 2041 and 4.9 percent by 2051. Most federal debt matures within a decade of it being issued; about 85 percent of existing federal debt is set to mature over the next ten years. Thus existing debt, and any new debt, will likely roll over at higher rates as they begin to rise.

In addition to upfront debt rolling over at a higher rate, borrowing for perpetual investments (for example, education) will issue new debt at those higher rates. The same cost-benefit analysis that makes borrowing for some investments appear worthwhile in 2021 may not apply in future years.

Even if rates remain relatively low, they do not eliminate the cost of new borrowing altogether. Without a plan to eventually repay debt, it will remain on the federal balance sheet forever.

An “Investment Exemption” Creates a Slippery Slope

Pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) budget rules are designed to make sure policymakers don’t make a bad fiscal situation even worse. While there are certainly times that more borrowing is warranted – for example, to combat a recession or address an unforeseen national emergency like COVID-19 – adding exemptions for specific types of policies risks undermining the rules themselves.

Establishing a PAYGO exemption for public investments would almost certainly lead policymakers to stretch the definition of investment to match their preferred policy agenda.

Nearly any policy – from physical infrastructure or health care to national defense or corporate tax cuts – has some element that could benefit the future. If budget rules allowed policymakers to avoid offsetting investments, it is hard to predict what would notbe classified as investments.

There are many worthwhile policies that policymakers across the political spectrum would love to enact, but all policy choices involve tradeoffs that must be evaluated. The purpose of budgeting is to lay out priorities and how to pay for them; deficit-financing investments avoids the hard decisions now so that future generations must make them instead. A better approach follows the simple rule that something worth having is worth paying for.

Conclusion

Responsible budgeting requires allocated resources where they can do the most good. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget commends policymakers for their recent focus on public investments and funding for younger Americans. These investments have the potential to produce a stronger economy and society for current and future generations.

However, it makes little sense to invest in the future by borrowing from it. Our current economic situation does not necessitate further borrowing, and our current fiscal situation – with large structural (consumption-driven) deficits and near-record levels of debt – demands the opposite.

Contrary to claims made by advocates, public investments do not generally pay for themselves – certainly not at the scale being discussed. And in fact, independent modelers have found fully-offset investments are often much more pro-growth than deficit-financed investments.

Low interest rates can justify front-loading new spending, but cheap borrowing doesn’t make new spending free, particularly when its likely to be rolled over into higher-yielding debt down the road.

And whatever arguments remain to deficit finance public investment make little sense when considering the slippery slope such it would create. Nearly all spending and tax breaks could be described as investment by someone. An ad-hoc decision to exempt investment spending from PAYGO rules would lead to far more borrowing down the road.

Rather than trying to justify why spending should not be paid for, policymakers should do the hard work to identify the revenue and spending reductions necessary to fund new investments. Neither a bipartisan infrastructure package nor a reconciliation package should be allowed to add to the debt. Rather, the plans should enact lasting reforms that reduce future deficits in order to further improve economic growth.

With the national debt headed toward record levels, we need offsets – not excuses.

1 $4 trillion represents total non-defense investment spending projected over the next ten years assuming that non-defense investments remain the same share of total non-defense discretionary spending as it is now. Another $2.7 trillion is projected to go to defense investment, but the vast majority of this is military equipment rather than investments that generate benefits for the broader public.