Analysis of the 2021 Social Security Trustees' Report

Today, the Social Security and Medicare Trustees released their annual reports on the long-term financial state of the Social Security and Medicare programs. Today’s reports are the first to incorporate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, recession, response, and anticipated recovery.

The latest Social Security projections show the program is quickly headed toward insolvency and highlight the need for trust fund solutions sooner rather than later. The Social Security Trustees found:

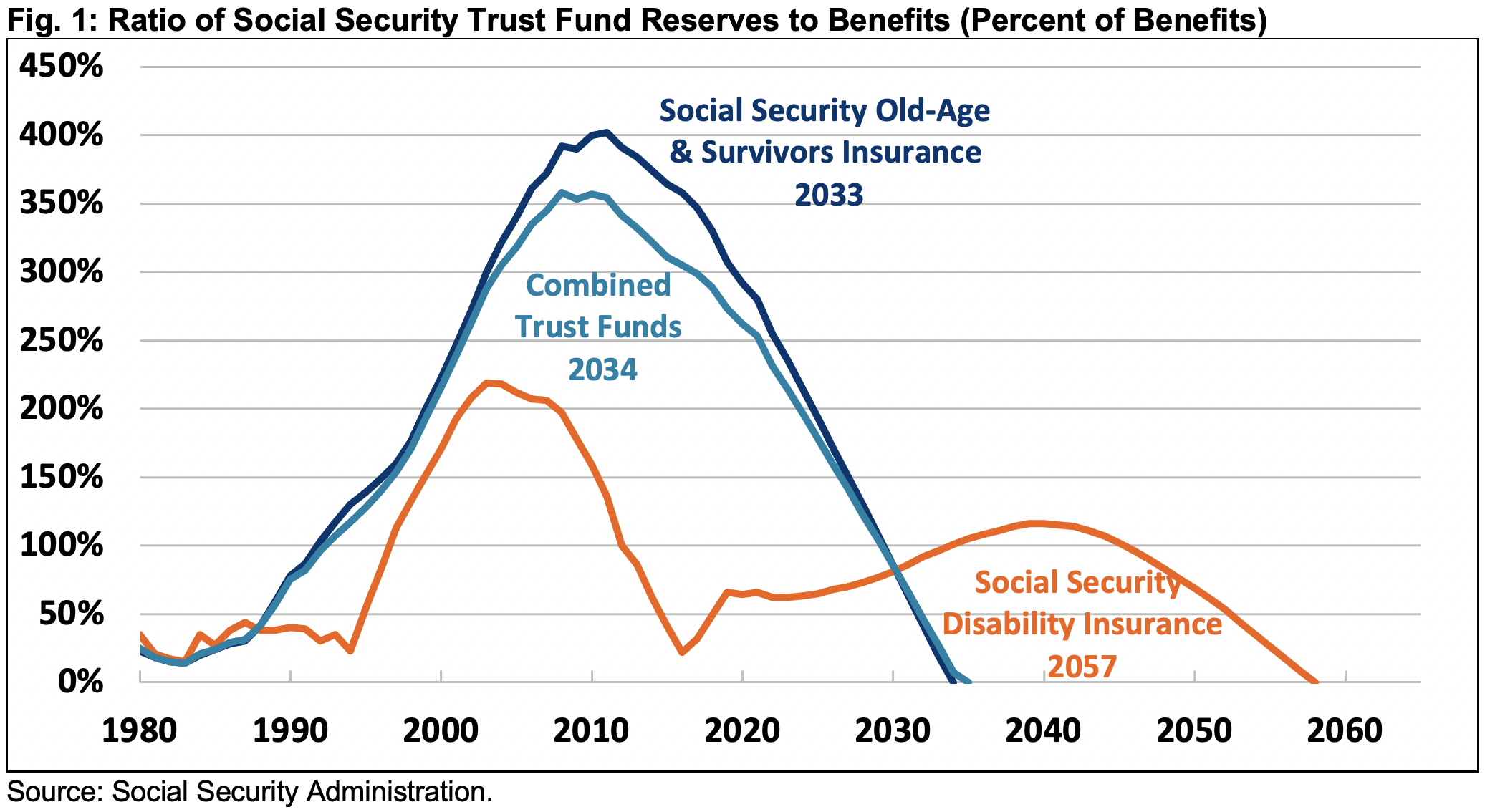

- Social Security is Only 13 Years from Insolvency. Social Security cannot guarantee full benefits to current retirees under current law. The Trustees project the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund will deplete its reserves by 2033 and the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund will become insolvent by 2057. The theoretical combined trust funds will exhaust their reserves by 2034, when today’s 54-year-olds reach the full retirement age and today’s youngest retirees turn 75. Upon insolvency, all beneficiaries will face a 22 percent across-the-board benefit cut.

- Social Security Faces Large and Rising Imbalances. According to the Trustees, Social Security will run cash deficits of $2.4 trillion over the next decade, the equivalent of 2.3 percent of taxable payroll or 0.8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Annual deficits will grow to nearly 5.0 percent of payroll (1.7 percent of GDP) by 2080 and total over 4.3 percent of payroll (1.4 percent of GDP) by 2095. Social Security’s 75-year actuarial imbalance totals 3.54 percent of taxable payroll, which is 1.2 percent of GDP or nearly $21 trillion in present value terms.

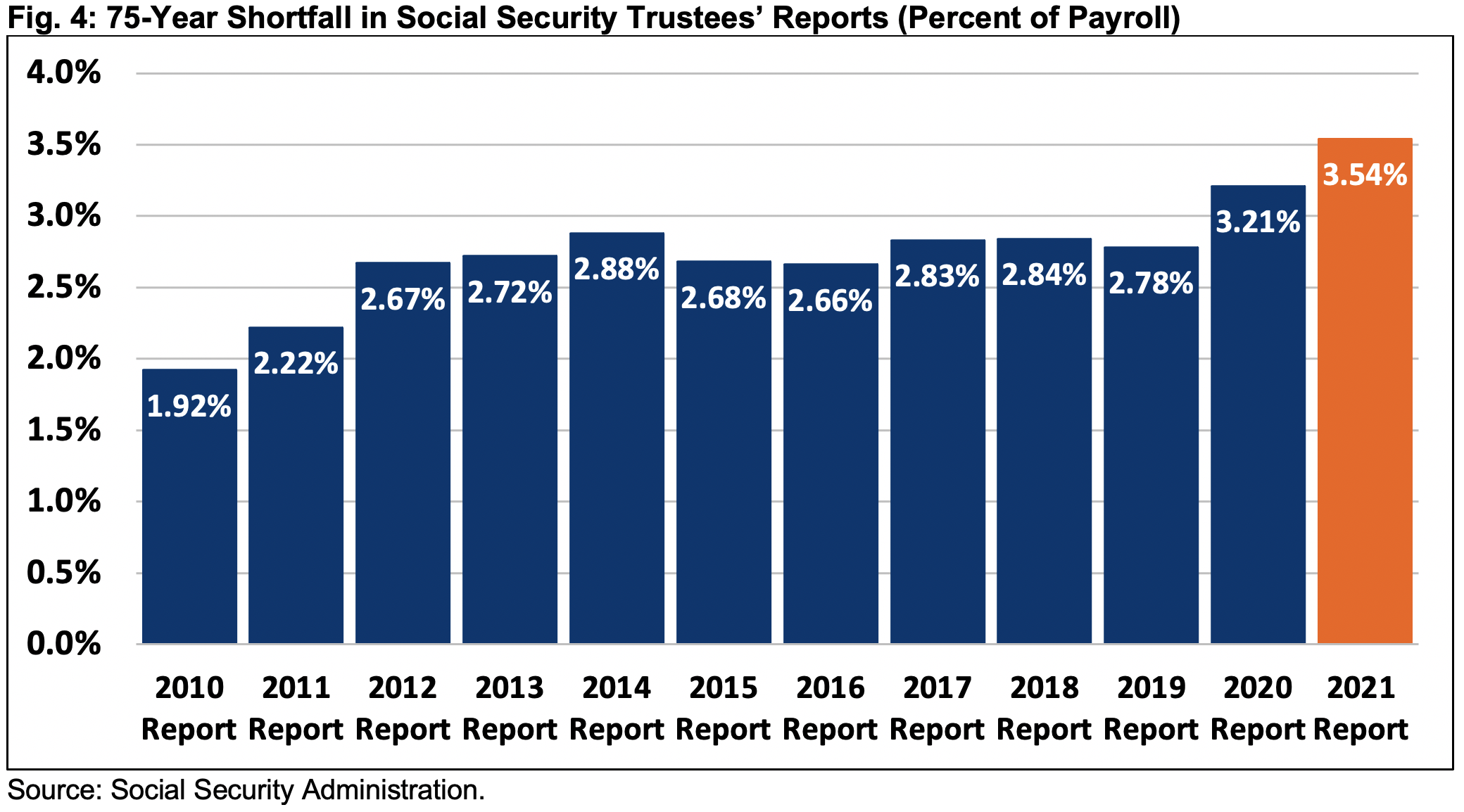

- Social Security’s Finances are Deteriorating. Social Security’s finances have worsened over the last year – insolvency is projected to occur a year earlier, and the 75-year actuarial deficit is over 10 percent larger. The 75-year shortfall is nearly 85 percent larger than it was projected to be in 2010.

- Time is Running Out to Save Social Security. Lawmakers have only a few years left to restore solvency to the program, and the longer they wait, the larger and more costly the necessary adjustments will be. Acting now allows more policy options, lets policymakers phase in changes more gradually, and provides more time for workers to adjust their work and savings if necessary.

Given the short timeline to address the looming insolvency of Social Security – and of Medicare Hospital Insurance (addressed in a forthcoming companion paper) – policymakers should seize any opportunity to enact trust fund solutions.

Social Security is Approaching Insolvency

The Social Security program is only 13 years from insolvency, and action must be taken promptly to prevent an across-the-board benefit cut for many current and future beneficiaries.

The Trustees project the Social Security OASI trust fund will deplete its reserves by 2033, while the SSDI trust fund will be exhausted by 2057. On a theoretical combined basis – assuming revenue is reallocated between the trust funds in the years between OASI and SSDI insolvency – Social Security will become insolvent by 2034.

Upon insolvency, all beneficiaries regardless of age, income, or need will face a 22 percent across-the-board benefit cut, which will grow to 26 percent by the end of the projection window.

The year 2034 is only 13 years away. The trust funds are on course to run out of reserves when today’s 54-year-olds reach the normal retirement age and today’s youngest retirees turn 75. For perspective, the average new retiree will live to age 85, meaning Social Security cannot guarantee full benefits for many current retirees, let alone for future beneficiaries.

Social Security’s insolvency could come sooner than the Trustees project. Based on recent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the trust funds will become insolvent by 2033.

Meanwhile, the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund is only five years from insolvency and will exhaust its reserves in 2026 according to the Medicare Trustees. We will provide an in-depth analysis of the 2021 Medicare Trustees’ report in a forthcoming companion piece.

Social Security Faces a Large and Growing Shortfall

The Social Security Trustees project the program will run ongoing deficits. The Trustees estimate the program will run a cash-flow deficit of $147 billion this year – the equivalent of 1.8 percent of taxable payroll or almost 0.7 percent of GDP – and will run $2.4 trillion of cumulative deficits over the next decade.

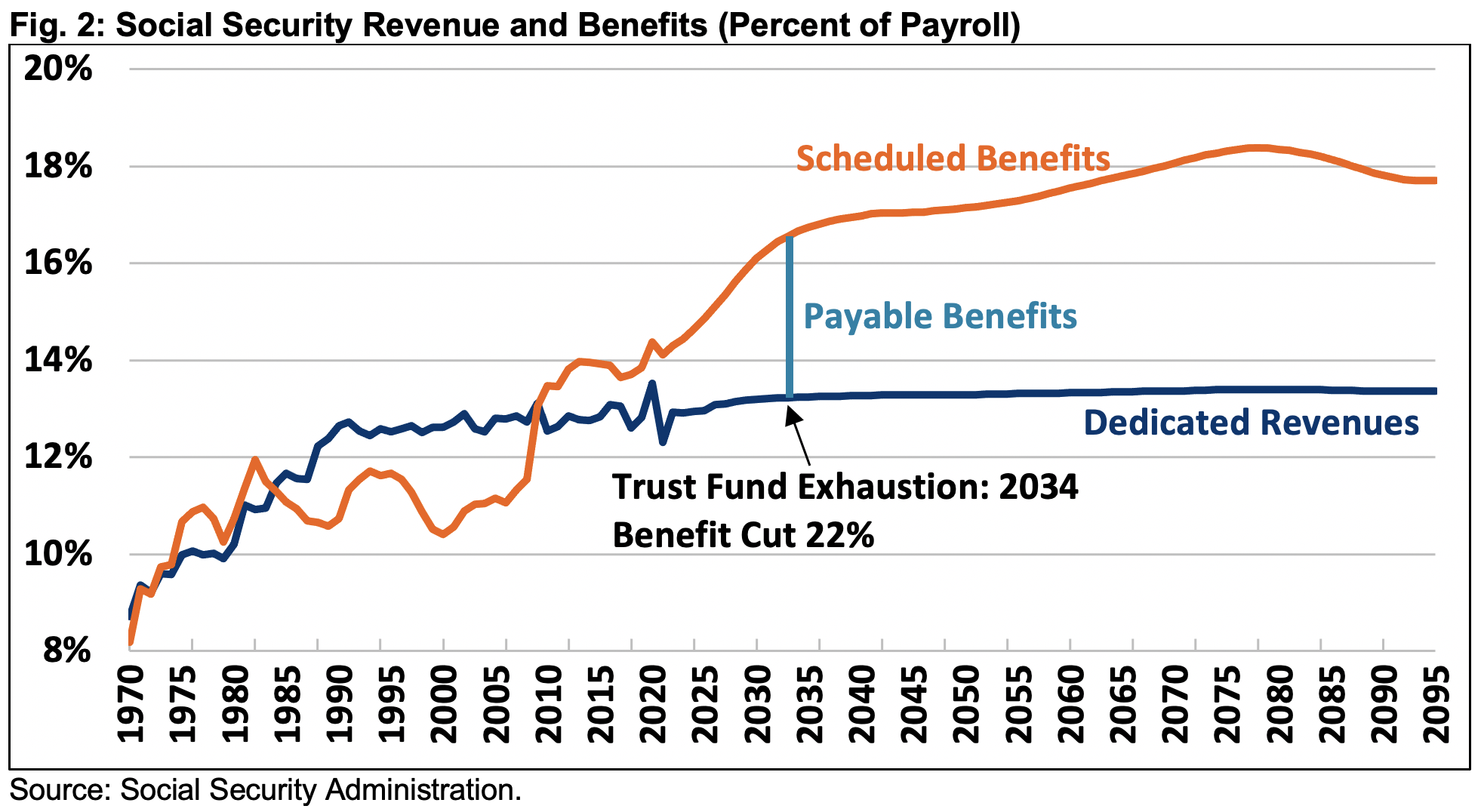

Over the long term, the Trustees project Social Security’s cash shortfall (assuming full benefits are paid) will grow to 3.1 percent of payroll (1.1 percent of GDP) by 2031, 3.7 percent of payroll (1.3 percent of GDP) by 2041, and a high of almost 5.0 percent of payroll (1.7 percent of GDP) in 2077. Costs will then decline, to just above 4.3 percent of payroll (1.4 percent of GDP) by 2095.

Social Security’s rising long-term shortfall is largely the result of rising costs, mainly due to the aging of the population. Total Social Security costs have already risen from 10.6 percent of payroll in 2001 to 14.1 percent of payroll in 2021 and are projected to rise further to 16.3 percent of payroll by 2031, 17.0 percent by 2041, and 17.7 percent of payroll by 2095. Revenue will fail to keep up, rising only slightly from 12.3 percent of payroll today to 13.4 percent of payroll by 2095.

Generally, the Trustees measure Social Security’s financial imbalance over 75 years. They find the program faces an actuarial shortfall of 3.5 percent of taxable payroll, which is 1.2 percent of GDP or nearly $21 trillion on a present value basis.

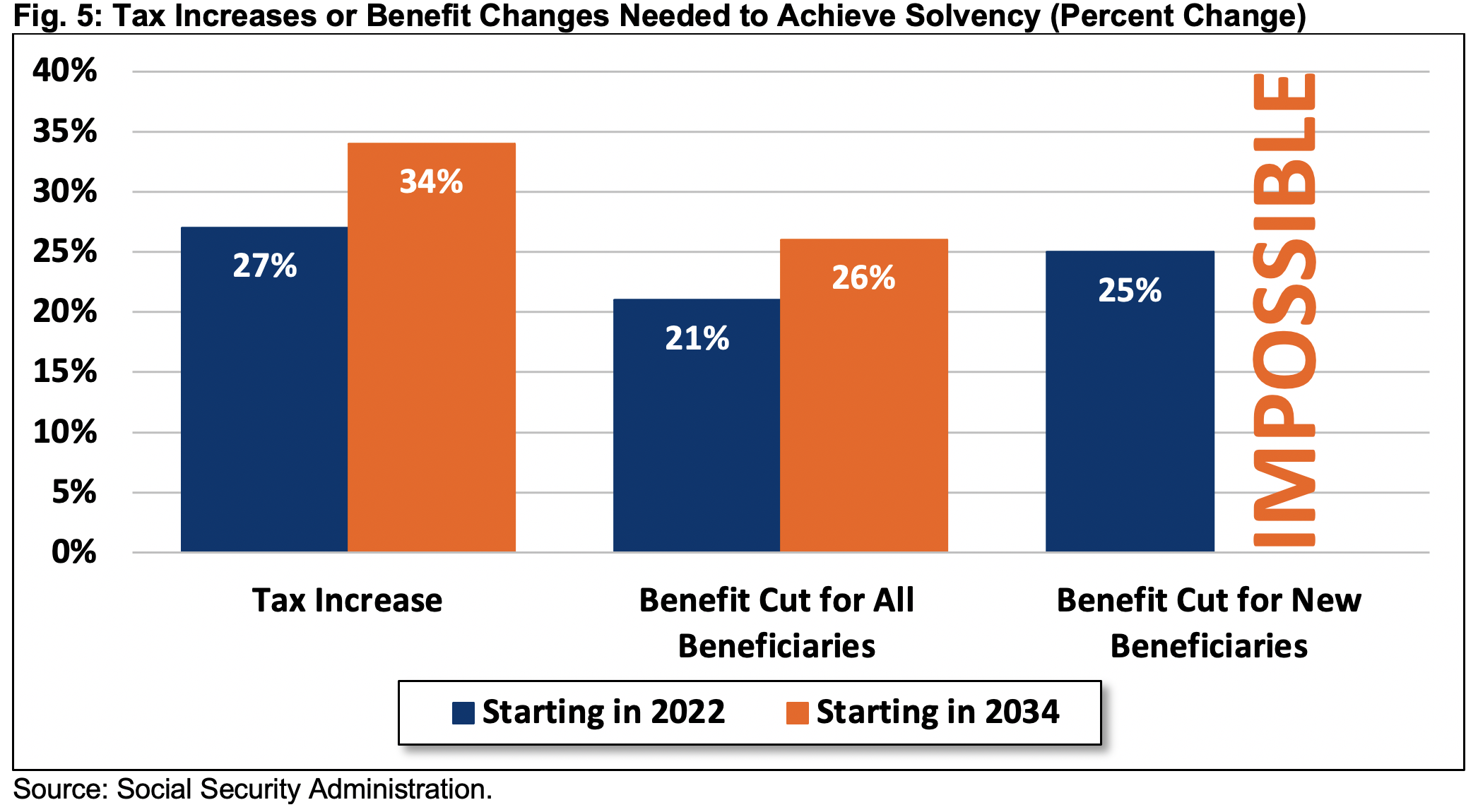

A plan to restore sustainable solvency to the program over the next 75 years would require the equivalent of increasing payroll taxes immediately by 27 percent, reducing spending by 21 percent for all current and future beneficiaries, or some combination. Actual reforms could be better targeted, rather than across the board, and phased in more gradually.

Social Security’s Finances Continue to Deteriorate

This year’s Trustees report is the first to incorporate the economic and public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy response and shows a worse overall outlook.

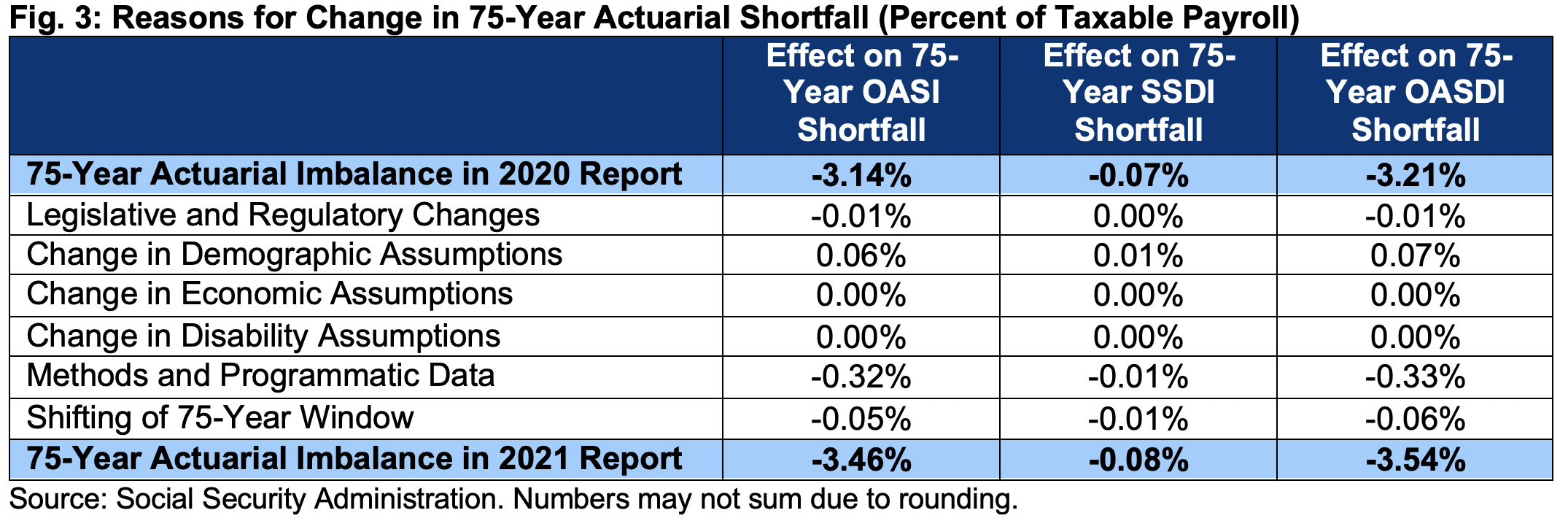

The last Social Security Trustees report, released in April 2020 but based on pre-COVID data, estimated an insolvency date of 2035 and a 75-year actuarial imbalance of 3.21 percent of taxable payroll. The Trustees now project Social Security will remain solvent until 2034, one year earlier than last year’s estimate. They estimate the 75-year shortfall of the Social Security trust funds is now 3.54 percent of taxable payroll, 0.33 percentage points higher than last year’s estimate.

These estimate are also somewhat worse than an interim assessment from the Social Security Chief Actuary, which found that the COVID-19 crisis advanced the insolvency date to 2034 and increased the 75-year actuarial imbalance by 0.07 percentage points to 3.28 percent of taxable payroll.

The advanced insolvency date appears to be driven in part by lower revenue as a result of wage income losses incurred from the COVID-19 pandemic (though total income including government benefits increased). However, the long-term deterioration relative to the last Trustees report – that is the 0.33 percentage point increase in 75-year shortfall – can almost entirely be attributed to changes in methodology and programmatic data.

Methodological changes, such as improvements in projections of future birth rates, the size of the labor force, and initial benefit levels of retired workers, along with an increase in the total fertility rate, ultimately increased the 75-year shortfall for OASI by 0.32 percent of taxable income and the shortfall for SSDI by 0.01 percent, or 0.33 percent for the theoretically combined Social Security trust funds relative to last year’s estimate.

Other changes mostly negated one another. For instance, while changes in demographic data and assumptions reduced the 75-year shortfall for the theoretically combined trust funds by 0.07 percent of taxable payroll – mainly due to an increase in the total fertility rate from 1.95 births per woman to 2.00 births – legislative and regulatory changes increased it by 0.01 percent, and a shift in the 75-year valuation period increased it by another 0.06 percent. Changes to data and assumptions relating to the economy had a negligible effect on the solvency of Social Security’s trust funds.

Despite prior years of improvements, the SSDI program’s solvency has worsened this year as well. The Trustees previously projected insolvency in 2065; they now project the program will remain solvent until 2057. Policymakers should continue to support improvements to disability programs, particularly those that can help to support individuals with disabilities to remain in or return to the workforce, but even with these efforts, the disability rolls are likely to swell.

The overall worsening in Social Security’s fiscal outlook follows a downward trend that has stretched on for more than a decade.

In 2010, the Trustees estimated the Social Security trust funds would be exhausted by 2037, meaning the insolvency date was three years later than currently estimated and 14 years further away than today. At the time, the program faced a 75-year shortfall of 1.92 percent of payroll. That shortfall rose to 2.22 percent of payroll in the 2011 Trustees Report, 2.67 percent in 2012, 2.73 percent in 2013, 3.21 percent in 2020, and 3.54 percent of taxable payroll in today’s Trustees report.

Delaying Fixes to Social Security is Costly

Changes must be made in order to ensure Social Security’s solvency, and they should be made sooner rather than later as the cost of delay is high.

In their conclusion, the Trustees recommend that “lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust to them.” Doing so would “allow more generations to share in the needed revenue increases or reductions in scheduled benefits.” Quick action would also give lawmakers choices in making targeted adjustments, enhancing benefits for vulnerable populations, and achieving the added benefit of pro-growth reforms.

Delaying action until 2034 would make the needed tax increases or benefit reductions about one-quarter larger than if action were taken today. According to the Trustees, 75-year solvency could be achieved with the equivalent of a 27 percent (3.36 percentage point) payroll tax increase today but would require a 34 percent (4.20 percentage point) increase in 2034. Similarly, Social Security solvency could be achieved with a 21 percent across-the-board benefit cut today, which would rise to 26 percent by 2034. Cuts to new beneficiaries would need to be 25 percent today, but even eliminating benefits for new beneficiaries in 2034 would not be enough to avoid insolvency.

Policymakers should seize any opportunity to enact trust fund solutions. Fortunately, many options exist to secure Social Security using either revenue changes, benefits changes or a combination of the two, as demonstrated by the Social Security 2100 Act, the Social Security Reform Act, and the Conrad-Lockhart plan, respectively. Other proposals can be designed with our Social Security Reformer tool.

Conclusion

The Social Security Trustees continue to warn that the Social Security program is significantly out of balance and just years from insolvency. Without reforms, Social Security will not to be able to pay full benefits to many current beneficiaries, let alone today’s workers and future generations. Action must be taken soon to avoid a 22 percent across-the-board cut to all beneficiaries in 13 years or less.

While the economic and health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic appear to have contributed to the advanced insolvency date and the increased 75-year actuarial shortfall, the increase in the 75-year shortfall itself can almost entirely be attributed to changes in methodology and programmatic data.

Still, the Trustees project Social Security faces a shortfall of 3.54 percent of payroll, which is 85 percent higher than they projected in 2010 and means policymakers will have to enact substantial revenue and/or benefit changes.

Fortunately, many well-known options to fix Social Security’s finances exist and could be enacted and implemented with political will. A number of comprehensive plans already exist to restore solvency, and our Social Security Reformer Tool allows anyone to design their own. Policymakers should also consider pursuing new, innovative solutions to promote economic growth and improve retirement security in concert with addressing the program’s finances.

To expedite action, the Time to Rescue United States Trust (TRUST) Act would establish bipartisan commissions to ensure Social Security, Medicare, and highway program solvency. Policymakers should consider this or a similar approach in order to reach consensus sooner rather than later.

Tags

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image