What Would It Take to Balance the Budget? An Update

The analysis below updates our previous analysis "What Would It Take to Balance the Budget?" to account for the Congressional Budget Office's latest ten-year budget projections.

It's encouraging that many in Congress are focusing more on our unsustainable fiscal situation and want a plan to improve the nation's fiscal outlook. When it comes to developing a budget blueprint, however, it is important to select an achievable fiscal goal rather than merely an aspirational one. Unfortunately, due to continued borrowing over the past several years, the desirable fiscal goal of budgetary balance has become much more difficult to reach, and it is highly unlikely it could be achieved in a decade or less, particularly if revenue, defense, and other parts of the federal budget are excluded from the solution. We recommend Congress adopt an aggressive but achievable fiscal goal in its budgets and any fiscal deals.

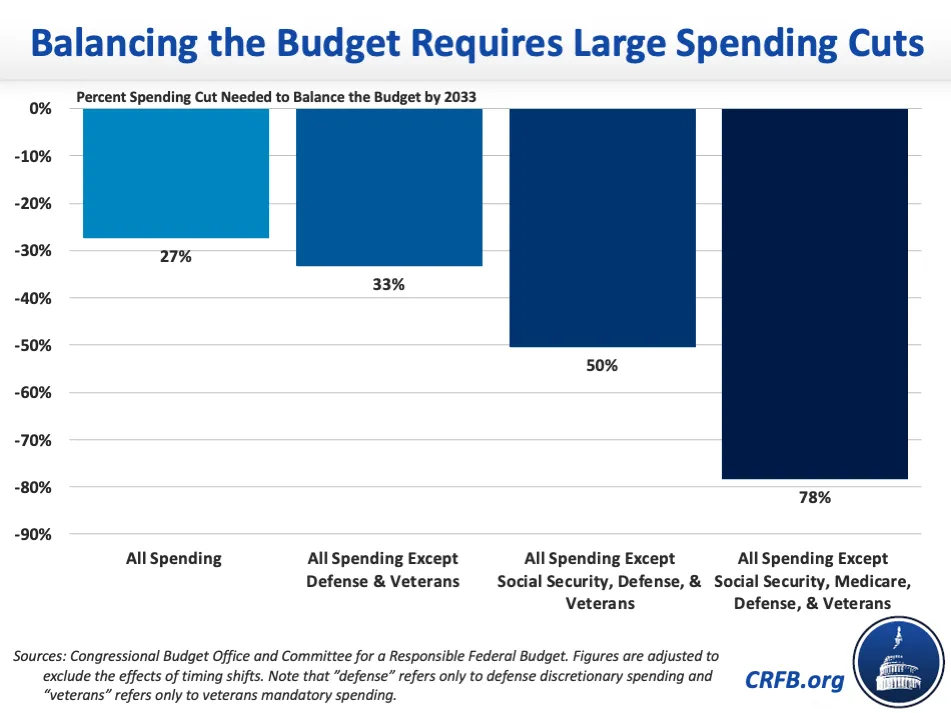

In this analysis, we show that in order to achieve budgetary balance within a decade all spending would need to be cut by 27 percent and the necessary cut would grow to 78 percent if defense, veterans, Social Security, and Medicare spending were off the table. These cuts would be so large that it would require the equivalent of ending all nondefense appropriations and eliminating the entire Medicaid program just to get to balance.

Balancing the budget has become increasingly challenging over the past 15 years. Efforts to show balance too often rely on unrealistically aggressive cuts, unspecified savings, rosy economic assumptions, and other budget gimmicks as a result. Successful budget actions in recent years have come mainly from more targeted deficit reduction efforts than from trying to meet overly aggressive fiscal goals.

And with deficits on course to reach $2.9 trillion by the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2033, balancing the budget is now harder than it has ever been.

The exact amount of savings needed for full budget balance depends on both the budget projections in the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) latest ten-year budget projections as well as the path of any proposed policies. Based on CBO's projections and a modified savings path of the CRFB Fiscal Blueprint for Reducing Debt and Inflation, we estimate that achieving balance would require $16.0 trillion of deficit reduction through FY 2033, including nearly $2.3 trillion of policy savings (and roughly $415 billion of interest savings) in 2033 alone.1

To achieve these savings without more revenue, we estimate all spending in FY 2033 would need to be cut by 27 percent; this figure rises to 33 percent if defense and veterans spending is exempted from the cuts. For a sense of magnitude, applying this cut across the board would mean reducing annual Social Security benefits for a typical new retiree by $10,000 to $13,000 in 2033. It would also mean laying off 1.1 to 1.4 million federal employees (more than two-thirds of the civilian workforce if the military were exempted) and removing 20 to 25 million people from Medicaid eligibility.

Excluding Social Security and Medicare from cuts would make the task of balance even more unrealistic. Without touching spending on defense, veterans, or Social Security, all other spending would need to be cut by 50 percent. Also excluding Medicare would mean that remaining spending would need to ultimately be cut by 78 percent.

The figures above do not include additional savings that might be necessary if policymakers choose to extend $3 trillion worth of tax cuts that have expired or are set to expire in the coming years.

To give a sense of just how challenging achieving balance in FY 2033 by controlling spending is, it would require doing one of the following:

- Eliminating virtually all defense and nondefense discretionary spending programs;

- Cutting Medicaid spending in half while eliminating all other mandatory spending outside of Social Security and Medicare;

- Eliminating all nondefense discretionary spending and ending the entire Medicaid program;

- Repealing Medicare, all income security programs, and all refundable tax credits; or

- Discontinuing all Social Security retirement and survivors' benefits.

Of course, the task is made more feasible by adopting a combination of different types of spending reductions and reforms along with new revenue, user fees, and stronger economic growth. But even then, achieving balance within a decade is incredibly challenging. Enacting the $7 trillion CRFB Fiscal Blueprint, which puts all parts of the budget and taxes on the table, would reduce the 2032 deficit to 2.9 percent of GDP (down from 6.6 percent) when incorporating stronger economic growth effects – still far short of balance.

Instead of shooting for balance within ten years, it would be wise to select a different target or timeline, such as:

- Balancing the primary (non-interest) budget (which would require $8.9 trillion of savings);

- Reducing or stabilizing debt as a share of the economy (for example, stabilizing debt at its current level of 97.5 percent of the economy would require $8.1 trillion of deficit reduction);

- Setting a ten-year savings target, such as $7 trillion of deficit reduction or $4 trillion of non-interest spending cuts; or

- Setting a longer time period than ten years.

Wanting to balance the budget is an admirable and desirable goal. However, the path to get to balance within ten years is likely infeasible, and it is virtually impossible if major parts of the budget and tax code are exempt from change. Policymakers should set aggressive but realistic fiscal goals, should keep all areas of the budget on the table, and should put forward policies to begin reducing deficits. The first step, of course, is to avoid actions that would worsen our already unsustainable fiscal situation. Policymakers should agree not to pass legislation that calls for any new borrowing. We commend the adoption of a specific and realistic fiscal target.

1 Because October 1 of FY 2034 falls on a weekend, roughly $150 billion of payments that are supposed to be made in FY 2034 will instead be made in FY 2033. Because of this timing shift, CBO presents an alternative set of projections that are adjusted to exclude this effect and thus show the structural deficit in FY 2033. We used these figures to calculate the savings needed to balance the budget in ten years as well as the spending cuts needed under various scenarios to achieve balance to match the intent of balancing the budget.