Student Loan Costs Drop to Near Record Lows After Reconciliation Reforms

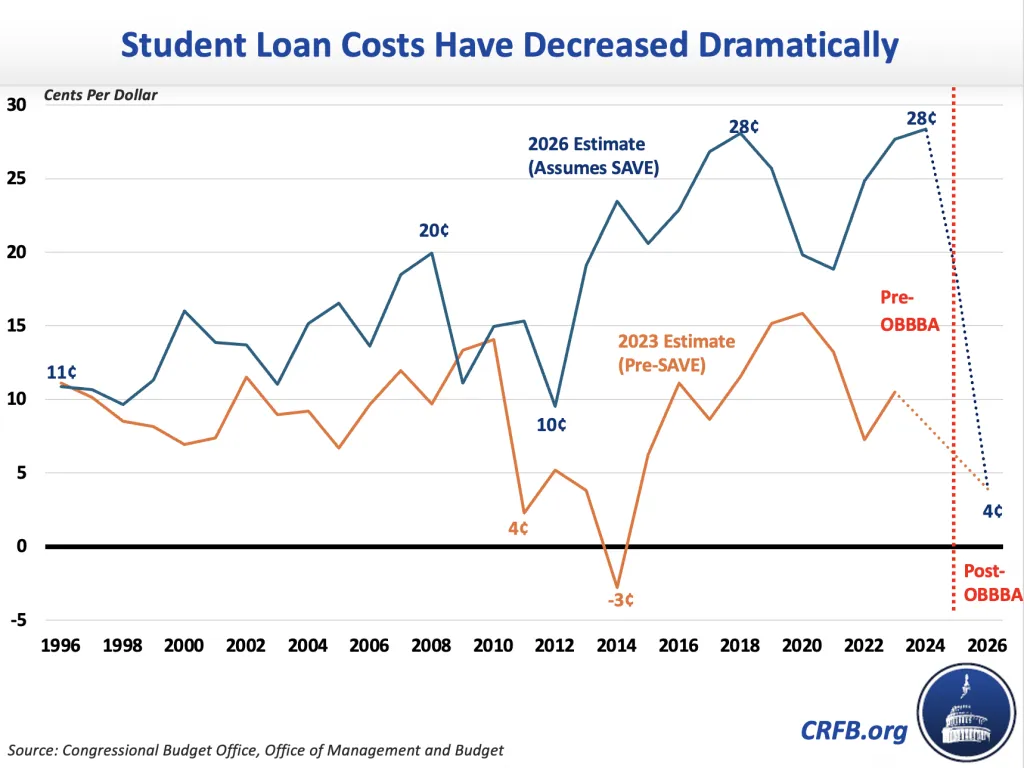

Note: This analysis has been updated from the original version to better reflect the effect that the Biden SAVE plan had on subsidy rates over time. As a result, while the new subsidy rate for the 2026 cohort of student loans is very low relative to recent history, it is not the lowest in the history of the direct loan program based on pre-SAVE estimates.

The fiscal cost of newly issued federal student loans is set to drop dramatically after the enactment of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), according to a new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

According to the CBO’s latest estimates:

- The federal government will lose 4 cents per dollar lent in 2026, on a present value basis, down from 18 cents in 2025.

- The lower cost is driven by those in repayment plans based on a borrower's income. The cost fell from an estimated 37 cent per dollar for undergraduate loans under the previous Income Driven Repayment (IDR) plans to less than 10 cents under the new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP).

- Grad PLUS loans in the RAP program lose 27 cents per dollar in 2026. However, those loans are currently phasing out, and it is not clear how much new graduate loans will cost.

- Under fair-value accounting, which incorporates market risk, student loans will cost the government 18 cents per dollar lent, including 44 cents for Subsidized Stafford loans enrolled in RAP.

The subsidy rates, which are essentially how much the government expects to lose per dollar lent, are much lower than previous years and reflect the roughly $315 billion in student loan savings over 10 years that CBO projected from OBBBA at the time of passage.

The Rise and Fall of Student Loan Subsidy Rates

Since the Direct Loan program was established in 1994, the federal government has issued roughly $1.6 trillion of direct federal student loans at an expected cost of over $330 billion.

Although the loan program was actually projected to make the federal government money in the early 2010s, current estimates show almost all cohorts of loans have cost money over the lifetime of repayment, with subsidy rates climbing over time. In a previous analysis, we showed that the estimated federal cost of student loans issued between 2015 and 2024 increased by $340 billion — from a projected gain of $135 billion in the 2014 baseline to an expected loss of $205 billion in the 2024 baseline. The current (as opposed to originally projected) subsidy rate for new loans rose from a low of 10% in 2012 to 28% in 2024.

Much of this cost explosion was driven by the expansion of income-driven repayment (IDR) programs (especially the Biden SAVE plan), which tie payments to a borrower’s income and became increasingly generous over time, especially for graduate students. The pandemic-era payment pause — enacted by Congress and then extended for over three years by both the Trump and Biden Administrations — further increased the subsidy rate on existing loans by eliminating years of payments.

CBO now projects that subsidy rate for new loans to drop to 4%, which would be one of the lowest rates for a cohort of loans since the creation of the Direct Loan program.

The reduction in the subsidy rate for new loans is driven primarily by two major changes enacted under OBBBA: the replacement of various IDR programs with the new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) and new borrowing limits for graduate students.

The Repayment Assistance Plan Is Significantly Less Costly than IDR

Under the old IDR plans (including SAVE), monthly payments were capped at between 5 and 10% of income above a "disregard" amount (150% to 225% of the federal poverty guidelines, depending on the plan) with remaining balances forgiven after 20 years.1 Unpaid interest accrual was also forgiven each month under SAVE. For lower income borrowers, payments were as low as $0 if the household was at or below 150% of the poverty line, or 225% under SAVE.

For new borrowers, OBBBA replaces these all with a new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP), which is less expensive and, in many ways, more progressive than prior plans.

Compared to the old IDR plans, RAP imposes a $10 minimum monthly payment that avoids zero dollar payments, reduces monthly payments by $50 per child, forgives any unpaid accrued interest each month, reduces principal by up to $50 per month for certain borrowers, forgives debt after 30 years (as opposed to 20), and uses a new formula that sets monthly payments at up to 10% of a borrower’s adjusted gross income (rather than a percentage of income above a disregarded amount). This last change effectively requires substantially larger payments from households earning over $100,000.2

These provisions greatly reduce the subsidy rate on loans in RAP relative to previous IDR plans. For example, under the previous IDR plans (including SAVE), CBO estimated the subsidy rate on undergraduate Unsubsidized Stafford loans was nearly 37%. Under RAP, the comparable loan subsidy rate is less than 10%.3

Borrowers Still Receive a Significant Subsidy

Although the average subsidy rate on new loans has fallen to an estimated 4%, the federal student loan program still offers a significant benefit for the borrowers both by taking on financial risk and by insuring against the risk of low income after leaving school.

CBO’s subsidy rates are calculated under the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), which measures the lifetime cost of loans by discounting future cash flows using Treasury interest rates. However, FCRA does not account for market risk — the risk that borrowers may not repay as expected — as a private lender would.

Under an alternative measure known as fair-value accounting, which incorporates market risk into the calculation and better matches the benefit relative to a private loan, the student loan program still provides a subsidy rate of 18 cents per dollar lent. Some budget experts have also argued that FCRA accounting measures the likely fiscal impact to the government while fair-value measures the subsidy to the borrower, meaning borrowers benefit 18 cents per dollar even as it only costs the government 4 cents.

The current program also offers a second type of risk protection to the beneficiary — RAP requires smaller repayments and forgives more interest for those who end up earning less after college than those who earn more (assuming the amount of debt borrowed is held constant).

Finally, subsidy rates, even on a FCRA basis, remain high for some types of loans. Each dollar of Graduate PLUS loans issued in 2025 and expected to be enrolled in IDR carried a 33% subsidy rate. Under RAP, the subsidy rate is 27%. 4 That being said, Grad PLUS is being phased out over the next three years and being replaced with capped graduate loans. It's unclear what the subsidy rate on new graduate lending will be due to the interaction between RAP and the new, stricter loan limits.

A New Era for Student Lending

These initial subsidy rates published by CBO point to a new era in the federal student loan program. Thanks to OBBBA, the government now expects to get back almost as much as it lends out — a huge reversal from recent years, when student loans were projected to lose hundreds of billions of dollars over a decade. It will be important for policymakers to maintain the integrity of these reforms and resist pressure to unwind the progress that has been made.

At the same time, there is still more work to do. While OBBBA reformed and reduced the cost of income-based repayment through RAP and imposed new loan limits on graduate students, it did not reform the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program (PSLF), which remains available to borrowers working in government or at nonprofits. PSLF allows remaining balances to be forgiven after just 10 years — well before RAP's 30-year timeline — with no cap on the amount that can be forgiven. As a result, high-balance graduate borrowers in public service can still receive six-figure forgiveness, which continues to drive up the subsidy rate on graduate loans. Reforming or capping PSLF would generate additional savings and further reduce the cost of the program.

In addition, the current student loan program continues to offer a poorly targeted in-school interest subsidy for some loans, the President still has at least some authority to forgive some student debt unilaterally (it is unclear how broad that authority is, as the courts have only ruled definitely on very broad debt cancellation), the President has just shown that he still thinks he can unilaterally stop collecting defaulted debt for political reasons, and many schools are still able to saddle borrowers with debt even when their post-graduate earnings outcomes are very low.

If Congress pursues a second reconciliation bill, it should build on OBBBA's student loan reforms in order to further improve the program and reduce federal deficits. Policymakers have made meaningful progress in rationalizing the student loan program — they should not stop here.

1 For low balance borrowers in SAVE, forgiveness was between 10 to 20 years for borrowers with balances between $12,000 and $20,000.

2 Additionally, the $100,000 is not inflation-adjusted, leading to even more savings in the out-years as more borrowers’ income grow from inflation. This progressivity is partially offset by the fact that unpaid accrued interest is forgiven each month, which can be a regressive benefit to high-debt, high-income borrowers in their early years of repayment.

3 CBO provided insufficient information to estimate the subsidy rate for the primary type of graduate loans.

4 That is likely because even with the more aggressive repayment regime in RAP, unlimited borrowing leads to high levels of forgiveness both in the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (PSLF), which forgives all outstanding debt after 10 years of payment in RAP, and even after 30 years of repayment for some very high debt borrowers.