Pell Grants Face a Big Shortfall

The Pell Grant program helps low-income students to fund their education by offering them up to $7,395 per year to fund tuition and other expenses. Funding for these grants come mainly from annual appropriations, along with reserves from prior-year surpluses.1

In light of recent Pell Grant expansions and reductions in discretionary spending, we estimate Pell Grant costs will exceed new funds and the program’s reserves will soon be depleted. Using Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Department of Education data, we estimate:

- Pell Grant costs will exceed appropriations funding each year for at least the next decade.

- The Pell Grant reserves will be exhausted by 2026 or sooner, leading to a significant funding cliff.

- The Pell Grant program faces a $35 billion to $95 billion ten-year shortfall, net of current reserves.

- Closing the Pell Grant shortfall will require higher appropriations, smaller benefits, tighter eligibility, or some combination. Further Pell grant expansions will widen the shortfall and grow needed adjustments.

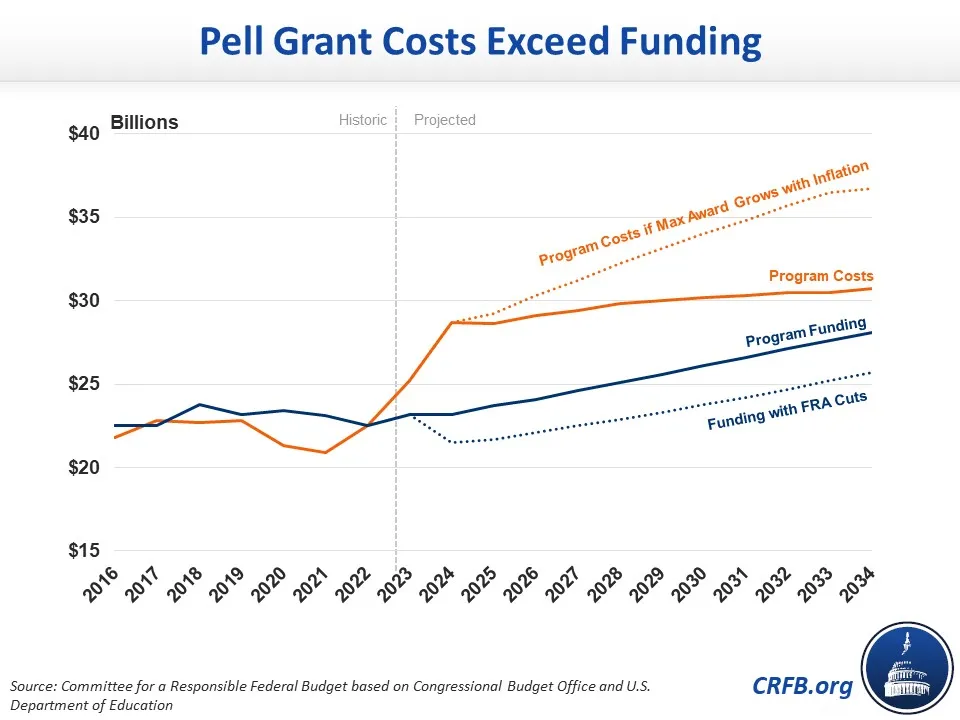

Last year, the discretionary portion of Pell Grant program cost about $25 billion, up from about $22 billion per year in the prior 7 years.2

In light of recently-increased benefit levels, reforms to the financial aid application process, and expected increases in enrollment, we estimate costs will grow to $29 billion this year and even higher in future years.

Current levels of appropriations will not keep up. Last year’s $23 billion appropriation was $2 billion short of costs. Assuming those levels are maintained this year as under the current Continuing Resolution and then grow with inflation, appropriations will come in $5 billion below costs in 2024 and $40 billion below costs over the subsequent decade.

Under alternative scenarios, that shortfall could be even larger. For example, if Pell Grant appropriations track the change in nondefense discretionary funding as scored by CBO under the Fiscal Responsibility Act – a roughly 8 percent cut this year and 1 percent increase next year – funding gap would increase nearly $25 billion or more over the next decade. And if the maximum discretionary Pell Grant award kept pace with inflation (it has grown 1.7 times the rate of inflation over the past three decades), costs would grow by $35 billion over the next decade.

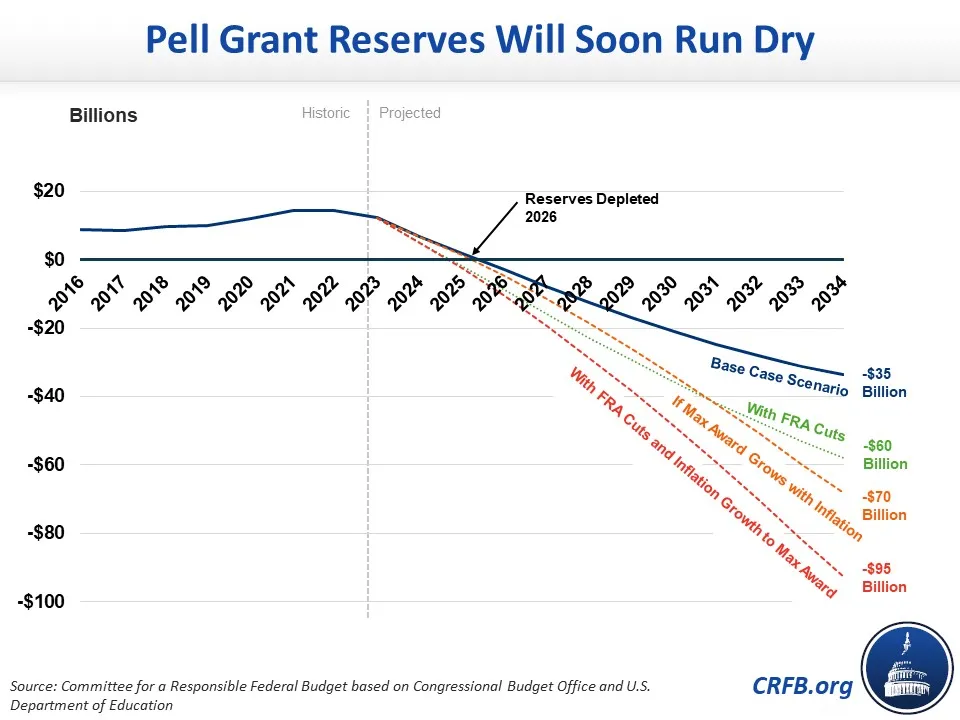

Under our base case, the $12 billion of Pell Grant reserves would be exhausted by 2026, leaving a nearly $35 billion shortfall by 2034. Closing this gap would require the equivalent of reducing benefits by 10 percent or increasing funding by 12 percent.

If Pell Grant funding was cut in line with the FRA caps, the reserves would be exhausted a year earlier – by 2025 – leaving a $60 billion shortfall by 2034. This would require an 18 percent cut in benefits or a 23 percent increase in funding to close this gap.

Growing benefit levels with inflation, meanwhile, would generate a $70 billion shortfall by 2034, requiring a 19 percent benefit reduction or 24 percent funding increase.

Funding Pell Grants in line with the FRA caps and growing benefit levels with inflation would leave a whopping $95 billion shortfall, requiring the equivalent of a 26 percent benefit reduction or 36 percent funding increase.

Given the size of these shortfalls, lawmakers should look for opportunities to find efficiencies and save money in the Pell Grant program and should identify spending cuts elsewhere in the budget to ensure appropriators can provide adequate funding to cover benefits. Certainly, it would be unwise to raid the existing reserves to further expand Pell Grant benefits without adequate offsets.

1In 2023, the $7,395 maximum annual benefit cost the federal government about $30 billion. Roughly $5 billion was funded on a mandatory basis to cover up to $1,060 of annual benefits. The remaining $25 billion -- covering up to $6,335 of benefits -- came from about $22 billion of new appropriations and over $1 billion of advanced appropriations from prior legislation. Remaining costs were funded out of reserves, which stood above $14 billion at the beginning for 2023. This analysis will focus mainly on the discretionary portion of Pell Grants funded from current and past appropriations.

2IThe mandatory add-on portion costs an additional $5 billion.