How to Save $600 Billion in Health Care While Protecting the Disadvantaged

In his testimony to the Super Committee, Fiscal Commission co-chair Erskine Bowles floated a compromise plan which would, among other things, reduce health spending by $600 billion -- more than $100 billion more than the Fiscal Commission did. Some, such as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), have suggested that this level of savings might be too big of a lift without hurting those who rely on the programs most. As they explain (emphasis added):

To his great credit, Bowles reiterated yesterday that a core principle of deficit reduction must be to “protect the disadvantaged.” Unfortunately, his “compromise” between a serious Democratic offer and a Republican stand-pat offer would lead almost inevitably to a significant violation of this important principle.

We don't agree -- it is possible to achieve well over $600 billion in Medicare savings while actually helping the most vulnerable. Here is one possible formulation of how:

| Policy | Savings | Effect on the Disadvantaged | ||

| Helps | Little Effect | Hurts | ||

| Reduce Provider Payments | $175 billion | X | ||

| Prescription Drug Rebates | $112 billion | X | ||

| Restrict Medigap | $93 billion | X | ||

| Reform Cost Sharing | X | |||

| Raise the Eligibility Age | $125 billion | X | ||

| Medical Malpractice Reform | $62 billion | X | ||

| Increase Income-Related Premiums | $40 billion | X | ||

| Total Savings | $607 billion | $280 billion | $327 billion | $0 |

Reduce Provider Payments -- $175 billion

Although the Affordable Care Act included significant reductions in provider payments, subsequent plans have shown that significant additional savings can be yielded by reducing and reforming payments to providers. For example, the Fiscal Commission identified $36 billion from reforming the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (savings compared to a freeze), $70 billion from reducing payments to hospitals for graduate medical education, and $26 billion from reducing payments for bad debts. On top of this, the President has proposed over $40 billion in savings from reducing and reforming acute care payments, along with billions more from rural hospitals and various other sources. Taken together, reductions totaling at least $175 billion could be put together. And though on the margins there may be some cases where access or quality of care might be indirectly affected, these lower provider payments will also mean lower Medicare Part B premiums for all beneficiaries. We score this as having little effect on the most disadvantaged.

Prescription Drug Rebates -- $112 billion

Applying the discounts that drug companies are required to provide in the Medicaid program to beneficiaries who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid and receive prescription drug coverage through Medicare Part D could save anywhere from $55 billion (Fiscal Commission) to $135 billion (President's submission) . Essentially, this policy would allow Medicare to better use its buying power to reduce drug costs, and these lower costs would be passed to the government in the form of a "rebate." We assumed enactment of the $112 billion CBO option which, as with reducing provider payments, would actually lower Medicare Part D premiums. Given that it could also lead to some cost-shifting outside of Medicare Part D, we'll again score this as having no large effect.

Restrict Medigap Policies -- $53 billion

Currently, many seniors buy supplemental coverage known as "Medigap" to cover their Medicare cost-sharing. Doing so not only increases utilization (and therefore Medicare spending) unnecessarily, but also turns out to be a bad deal for beneficiaries. Restricting the ability of Medigap plans to cover near first-dollar could save $53 billion (more if combined with the option below), while reducing costs for most Medicare recipients.

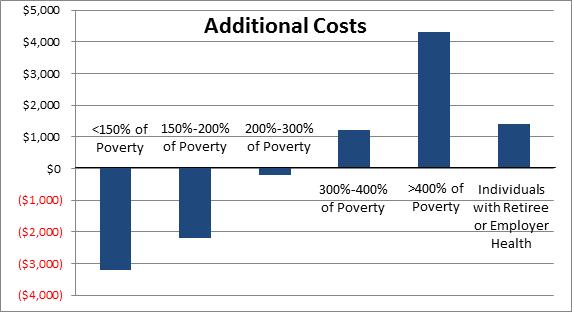

In fact, the Kaiser Family Foundation has studied the impact of Medigap restrictions and found that about 80 percent of Medigap users would face lower out-of-pocket costs under this reform -- by an average of $750 per year. Here is a graph, which should confirm that this policy indeed helps to reduce costs for most of the disadvantaged:

Lawmakers could also consider restricting the amount of Medicare cost-sharing that military retirees receive through TRICARE for Life, essentially a Medigap-style reform for military retirees, which could generate another $40 billion in savings.

Reform Medicare Cost-Sharing -- $32 billion

Currently, Medicare cost-sharing is a hodge-podge of deductibles, copayments, and other rules which both encourage overuse, create confusion, and fail to protect against catastrophic risk. CBO's Budget Options includes a policy that would rectify this -- replace those rules with a simple $550 deductible (combined for Part A and B), 20 percent uniform coinsurance, and a $5,500 cap above which Medicare covers all costs.

This change would save the government over $30 billion, but what about beneficiaries? According to a previous CBO analysis, the most vulnerable would actually be helped.

True, in a given year, most people (78 percent in their analysis) would experience higher cost sharing -- about $500 worth. But those with serious health expenses -- the top 9 percent in terms of health spending -- would see huge reductions in their out of pocket costs -- by about $4,500. If you do that math on that, it means that this option to reform cost-sharing would actually reduce mean cost sharing by $15 per person, due to the new protections being offered for those with high costs (which, though only a tenth of the population in a given year, will include the majority of beneficiaries at some point in their lifetime).

In other words, while beneficiaries cost-sharing expenses may be higher in any given year when they don't have major illnesses or medical conditions, beneficiaries would be protected from catastrophic health care costs, which are one of the leading causes of bankruptcy in the country. Now that's protecting the most vulnerable!

It is also important to remember that Medicaid covers the cost-sharing requirements for approximately 18 percent of Part B enrollees with low income and limited assets, so these beneficiaries would not be affected by cost-sharing changes.

Raise the Medicare Eligibility Age -- $125 billion

Gradually raising the eligibility age to 67 would boost savings by about $125 billion over ten years, and we've made a strong case for that option here -- arguing that doing so would both encourage work and better target scarce resources. What we didn't show, however, is that even according to the Kaiser study which opposes raising the age (and which CBPP cites), doing so would help the most disadvantaged. According to Kaiser, about 30 percent of total seniors age 65 to 67 (after full phase-in) and 60 percent of those without employer coverage would see their out of pocket costs reduced. That's because Medicaid and the health insurance exchange are in some cases more generous than Medicare.

So who is it that sees their costs go down? You guessed it -- the most vulnerable and disadvantaged. Those with no employer coverage making less than 150 percent of the poverty line see on average a $3,000 reduction in costs, those under 200 percent a $2,000 reduction, and even those under 300 percent of poverty ($33,000 for an individual) see a reduction in their out-of-pocket costs.

CBPP raises a fair concern that without ACA in place, raising the Medicare age would not protect these groups. But that's not an excuse not to pursue the policy. Policymakers could tie increases in the eligibility age to the implementation of ACA as Senators Lieberman and Coburn did in their health proposal.

Enact Tort Malpractice -- $62 billion

Reforming malpractice laws could save over $60 billion in health care programs, and would benefit nearly everyone who has health insurance --that is, except for trial lawyers. The current malpractice system increases both direct costs for doctors and hospitals (which they pass on), and encourages the overuse of defensive medicine. According to CBO, a robust set of reforms would not only save the government money, but reduce overall health care costs by 0.5 percent -- thus helping everyone, including the most disadvantaged.

Expanding Means-Testing -- $40 billion

Currently, higher earning Part B and Part D beneficiaries pay more in premiums than everyone else. This income-relating could be further enhanced both but increase their premiums more and by freezing or reducing the threshold against which the income-relating begins. By definition, strengthening the means-tested provisions in Medicare would ask those with more resources to pay a little more for health care while protecting the most vulnerable. Depending on how it is structured, such changes could also generate $40 billion over ten years.

* * * * *

Adding it all up gets you to over $600 billion in savings without putting any additional burden on the most vulnerable Americans, and in many cases reducing their burden. And, of course, there are many other options out there to reform Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, FEHB, and other health programs, and to do so without imposing large new costs on those who rely most on those program.

The worst thing we could do for the most disadvantaged, though, is nothing. In a fiscal crisis scenario, we would be forced to make immediate cuts to spending and/or tax increases to bring the budget under control. It would be much more difficult under that scenario to protect the most vulnerable from budget reforms.