EARN Act Would Cost $80 Billion Without Gimmicks

This analysis is an update to a previous analysis of the Enhancing American Retirement Now Act to account for the introduction of the legislation itself and a recent cost estimate published by the Congressional Budget Office. The original analysis can be found here.

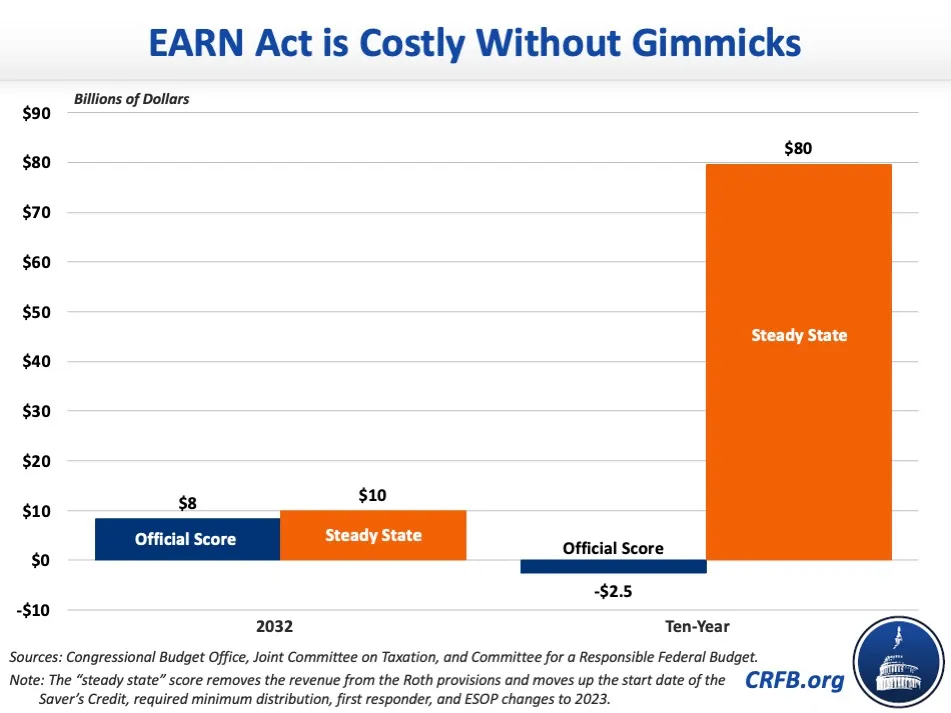

The Senate Finance Committee recently reported out the Enhancing American Retirement Now (EARN) Act, a bill designed to encourage private retirement savings. The $41 billion cost of the bill is offset with timing gimmicks related to Roth Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and the elimination of a tax deduction for pass-through entities of qualified charitable contributions of conservation easements. Even with the timing gimmicks, the bill would increase annual budget deficits from 2028 onward. In the steady state, we estimate the EARN Act would cost $80 billion over ten years, including $10 billion in 2032 alone.

The EARN Act, which is intended to build on the SECURE Act passed in 2020, proposes several changes to encourage more savings, including expanding the saver's credit and reforming it to be a matching contribution rather than cash, increasing the "catch-up" contribution limit to retirement savings accounts for individuals aged 60 to 63, raising the age for required minimum distributions from 72 to 75, and allowing penalty-free withdrawals in certain instances. These changes would cost $41 billion through 2032, including $8 billion in 2032 alone.

This $41 billion cost is more than offset on paper by provisions allowing employer contributions to 401(k)s to be put into a Roth IRA and requiring catch-up contributions to be put in Roth IRAs. The EARN Act also includes a provision that would eliminate the tax deduction for pass-through entities of qualified charitable contributions of conservation easements. As a result, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has scored the legislation as cumulatively reducing budget deficits by over $2 billion through 2032 and increasing them by nearly $8 billion in 2032.

Unfortunately, the EARN Act relies on gimmicks and timing shifts to achieve its supposed deficit reduction. The legislation would expand the saver's credit, which provides lower-income taxpayers with a tax credit for contributing to retirement accounts and Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) accounts, which allow certain people with disabilities to contribute to accounts whose earnings can grow tax-free. The bill would also reduce taxes for first responders and employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). However, it delays the onset of these policies for four or five years. It also increases the required minimum distribution age for IRAs from 72 to 75, which would allow retirees to accrue more non-taxed earnings in those accounts, but it delays the increase to 2032. Under previous versions of the bill, the required minimum distribution age would have increased gradually rather than all at once.

Perhaps most troubling is the fact a large part of the legislation's offsets are policy changes that would shift the time of tax collections rather than the amount of tax collections themselves. Specifically, the EARN Act would require and allow greater use of Roth contributions for retirement accounts, which are taxable when made but allow for tax-free withdrawal (traditional IRAs permit the opposite). While these provisions would generate $36 billion of new revenue over the first decade, they would reduce future revenue as retirement funds are withdrawn. The net effect of these changes is somewhat uncertain, but it is very likely that these policies would be net deficit-increasing when evaluated on a present-value basis.

The only real offset is a provision to disallow charitable deductions for qualified conservation contributions from pass-through entities, which CBO estimates would raise $8 billion of new revenue over a decade.

Budgetary Effect of Enhancing American Retirement Now Act

| Policy | Official Cost/Savings (-) | Steady State Cost/Savings (-) |

|---|---|---|

| Reform saver's credit | $10 billion | $18 billion |

| Increase required minimum distribution age | $4 billion | $30 billion |

| Exclude from taxation first responder retirement payments | $5 billion | $11 billion |

| Defer 10 percent of gain for ESOPs sponsored by S corporations | $2 billion | $6 billion |

| Provide tax credit for small employer contributions | $3 billion | $3 billion |

| Increase "catch-up" limit in early 60s and index to inflation | $2 billion | $2 billion |

| Other provisions | $16 billion | $17 billion |

| Subtotal | $41 billion | $87 billion |

| Allow or require conversions to Roth IRAs | -$36 billion | * |

| Eliminate tax deduction for qualified charitable contributions of conservation easements | -$8 billion | -$8 billion |

| Total | -$2.5 billion | $80 billion |

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation, and Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Note: Steady state removes revenue from Roth provisions and assumes saver's credit, required minimum distribution, first responder, and ESOP changes start in 2023.

*The Roth provisions will raise revenue in the short term but lose revenue over the long term. We expect the provisions would ultimately lose revenue on a present value basis but assume zero net cost here.

Under a steady state cost estimate, which assumes the benefit expansions would be enacted by 2023 or 2024 and the timing shift effects of the Roth provisions are removed, the EARN Act would cost $80 billion through 2032 rather than being deficit-reducing. In 2032, the net cost of the legislation would total $10 billion in the steady state, up from $8 billion as written. Even as written, the second-decade cost of the legislation could very likely exceed $100 billion – perhaps significantly so.

The EARN Act would increase budget deficits over the long term, despite the Roth gimmicks and timing shifts included in the legislation. It would clearly worsen budget deficits once the gimmicks are removed. As with previous iterations of the EARN Act, policymakers should find actual and larger pay-fors to make the legislation fiscally responsible.

As policymakers consider whether to include costly provisions in an end-of-year package, they should commit to no new borrowing for the rest of 2022. If the EARN Act – or a version of it – makes its way into a year-end package, it should be fully paid for over the next decade and over the long term with some combination of increased revenue and/or reduced spending.