CBO Projects Social Security Will Run Out of Funds in 13 Years

As we've warned many times before, Social Security is rapidly headed toward insolvency. Recent projections from CBO's Long-Term Budget Outlook suggest the program may run out of funds faster than many believe.

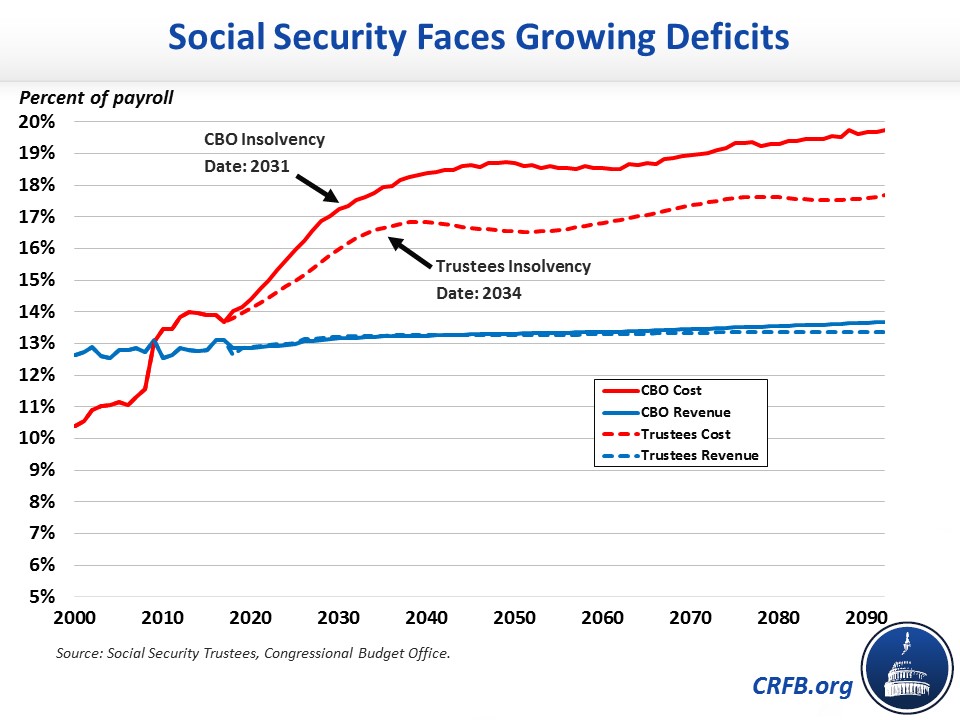

While the program’s Trustees project Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) will be insolvent by 2032 and the old-age program will be insolvent by 2034, new estimates from CBO project insolvency dates of 2025 and 2032, respectively. On a combined basis, CBO projects the Social Security trust funds will become insolvent by 2031, three years earlier than the Trustees project.

Since 2000, Social Security's costs have risen from 10.4 percent of payroll to nearly 14 percent of payroll. CBO projects costs will continue to rise to 18 percent of payroll by the mid-2030s, headed to 20 percent of payroll by the turn of the century. Meanwhile, revenue will rise only modestly, from just below 13 percent of payroll today to less than 14 percent by the turn of the century.

As a result, Social Security's deficits will explode. As recently as 2009, the program was in cash balance. In 2018, CBO projects a deficit of 1.2 percent of payroll, and that deficit will grow to above 4 percent of payroll by 2030, above 5 percent by 2040, and over 6 percent by the end of the 75-year projection window.

In the coming years, these deficits will deplete the Social Security trust fund. Just 13 years from now – when today's 54-year-olds are entering retirement and today's youngest retirees turn 75 – CBO projects trust fund exhaustion. At that point, the law requires benefits to be limited to revenue, meaning a 25 percent across-the-board cut for all beneficiaries regardless of age or income.

These estimates are similar to last year's, though more pessimistic than the projections made by Social Security's Trustees.

See how old you will be when Social Security runs out here:

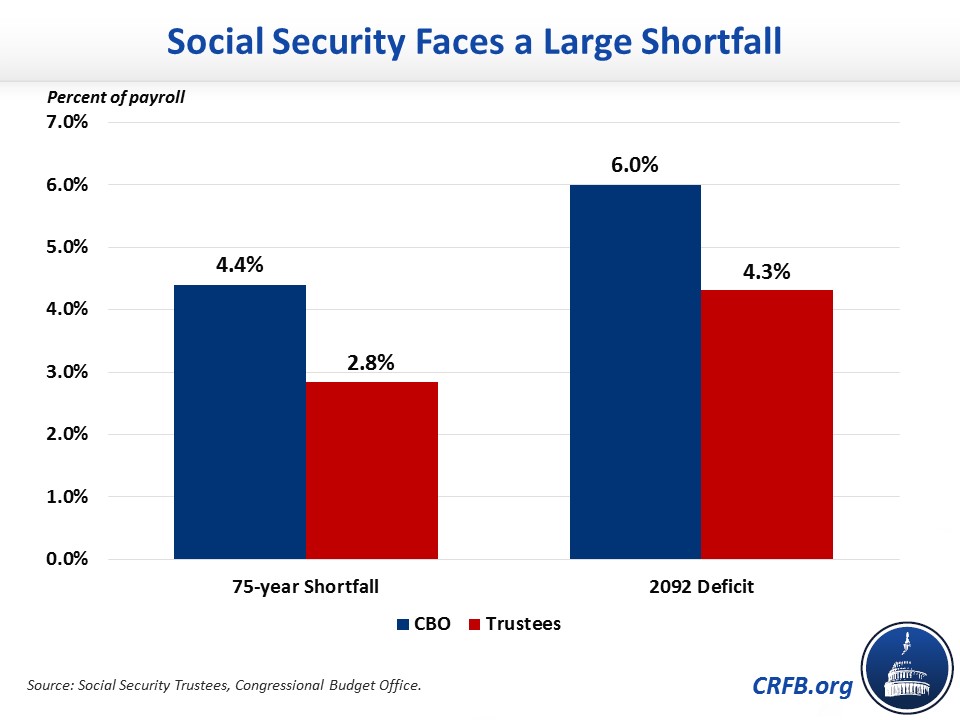

CBO projects a 75-year actuarial shortfall of 4.4 percent of payroll and 1.5 percent of GDP, which is more than 50 percent larger than the Trustees project. That means making the program solvent for 75 years would require the equivalent of an immediate 35 percent (4.4 percentage point) increase in the payroll tax rate or an immediate 25 percent cut in benefits.

By the 75th year, further adjustments would be needed to maintain solvency. CBO projects a shortfall of 6 percent of payroll (1.9 percent of GDP) in 2092, compared to 4.3 percent of payroll (1.5 percent of GDP) for the Trustees.

The difference between CBO and the Trustees is driven by more optimistic economic assumptions by the Trustees. They project faster long-term economic growth, less growth in income inequality, shorter life expectancy, higher fertility, and higher interest rates on trust fund assets.

| CBO | Trustees | |

|---|---|---|

| Insolvency Date (combined) | 2031 | 2034 |

| Automatic Benefit Cut at Insolvency | 25% | 21% |

| 75-year Shortfall | 1.5% of GDP (4.4% of payroll) |

1.0% of GDP (2.8% of payroll) |

| Deficit in 2092 | 1.9% of GDP (6.0% of payroll) |

1.5% of GDP (4.3% of payroll) |

| Tax Increase Needed for 75-year Solvency | 35% | 22% |

| Benefit Cut Needed for 75-year Solvency | 25% | 17% |

The differences between CBO and the Trustees highlights the need for policymakers reforming Social Security to include policies that are robust to different economic and demographic changes. For example, the retirement age could be indexed to life expectancy and the taxable maximum set to tax a certain share of wages, rather than simply raising the age and taxable maximum to pre-specified levels.

Despite some differences, though, CBO and the Trustees’ projections make one thing clear: Social Security faces a large shortfall and is on a clear path toward insolvency.

Restoring solvency will require tough tradeoffs, but acting soon can prevent abrupt benefit cuts, better target adjustments to those who can most afford them, allow for smart policy changes that improve the program and promote economic growth, give workers more time to plan for retirement, and allow the solution to be more equitably distributed among generations.

The longer Congress waits to enact such changes, the larger they will need to be and the fewer people they will be concentrated on.