Analysis of CBO's 2020 Long-Term Budget Outlook

Today, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its 2020 Long-Term Budget Outlook, which shows the federal budget is on an unsustainable long-term trajectory. Overall, the situation is much worse than the agency’s 2019 pre-pandemic projections. CBO’s report shows:

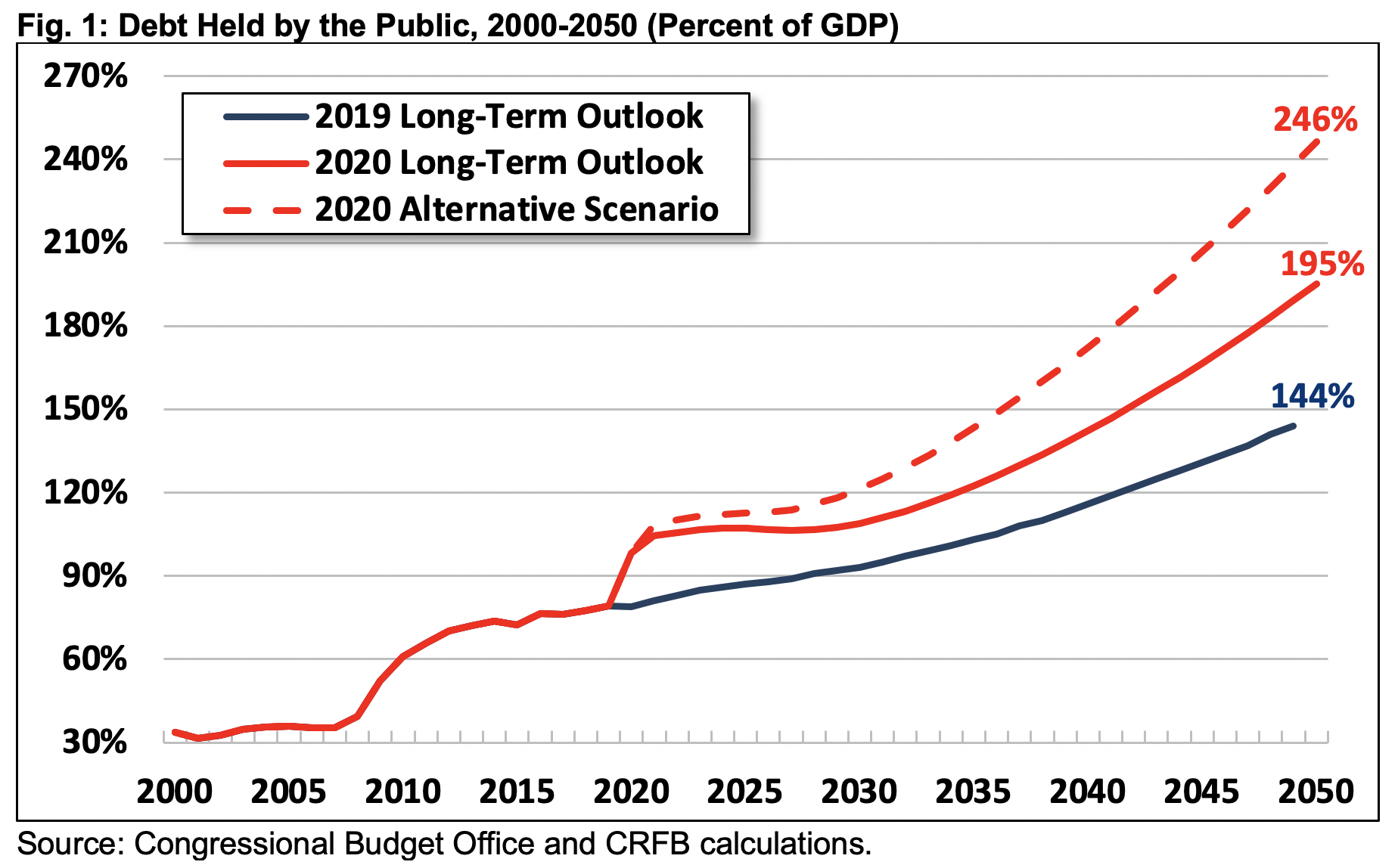

- Debt Will Nearly Double the Size of the Economy By 2050. Under current law, CBO projects federal debt held by the public will rise from 79 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 to 195 percent by 2050. Under a more realistic scenario, we estimate debt could reach 245 percent of GDP by 2050.

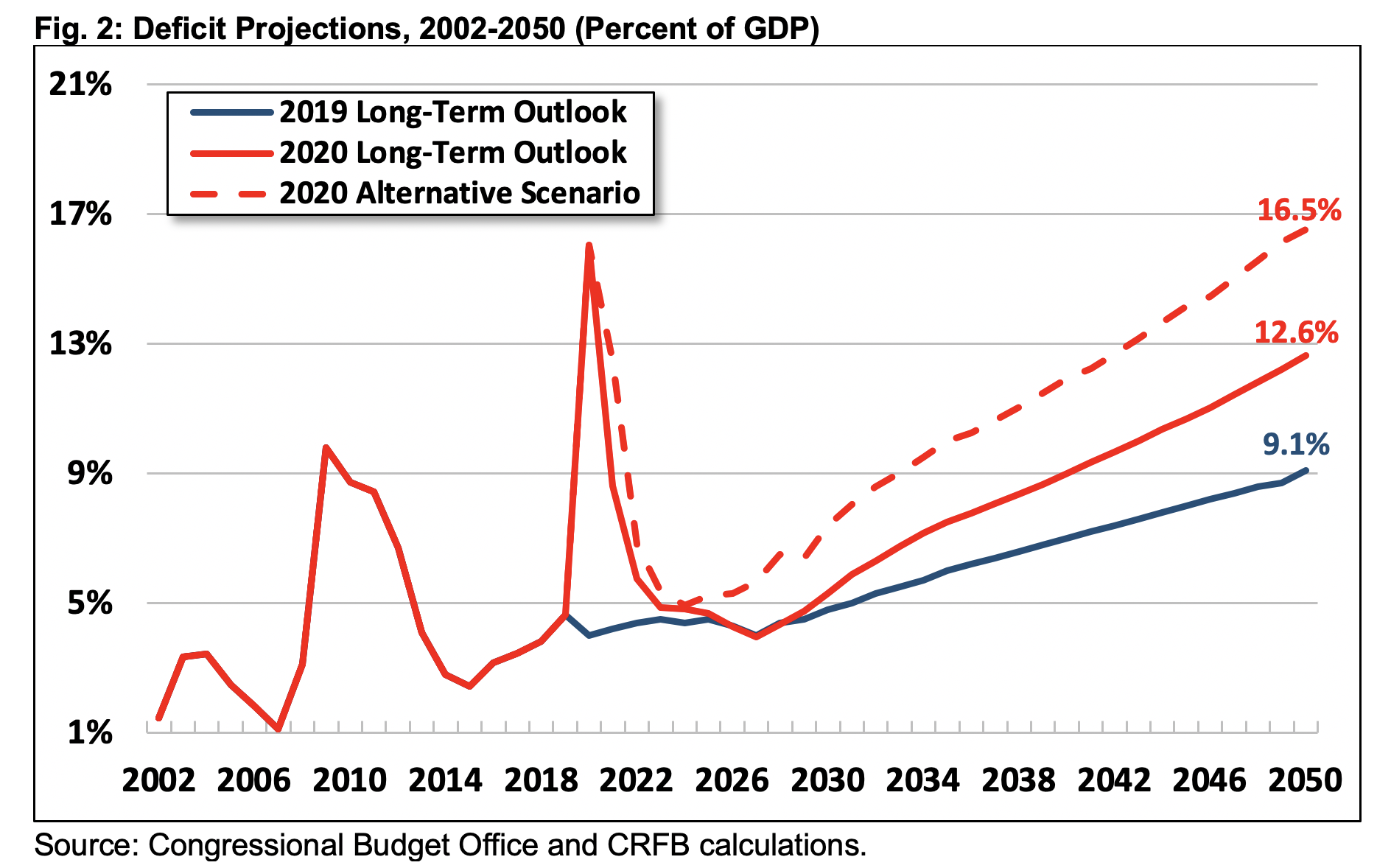

- Deficits Will Explode. By 2050, CBO projects annual deficits will grow to 12.6 percent of GDP under current law. This is lower than the COVID-driven 16.0 percent deficit in FY 2020, but over four times as high as the 3 percent of GDP average seen over the past 50 years and higher than at any point in modern history outside of World War II and the current crisis.

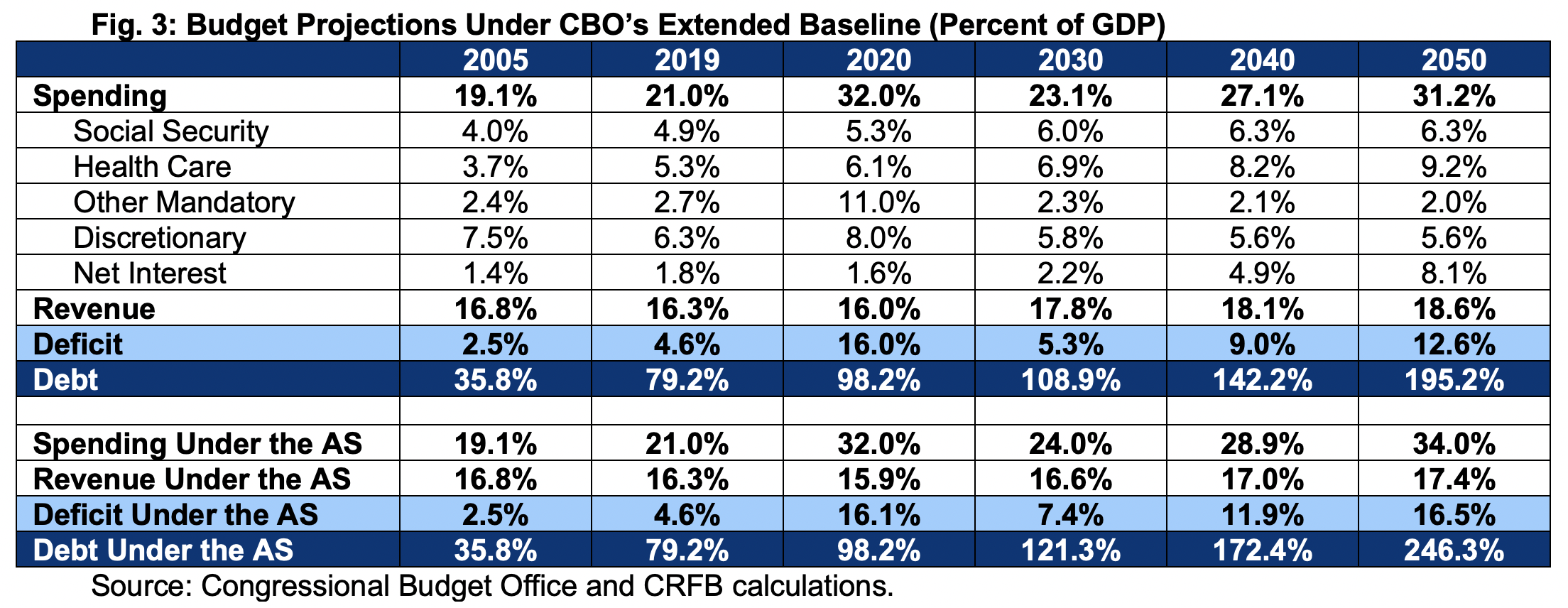

- Spending Growth Will Outpace Revenue. CBO projects spending will grow from 21.0 percent of GDP in 2019 to 31.2 percent by 2050, while revenue will grow from 16.3 percent to 18.6 percent of GDP. In the immediate term, spending temporarily spikes and revenue falls as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. More than all of the spending growth can be attributed to rising health, retirement, and interest costs.

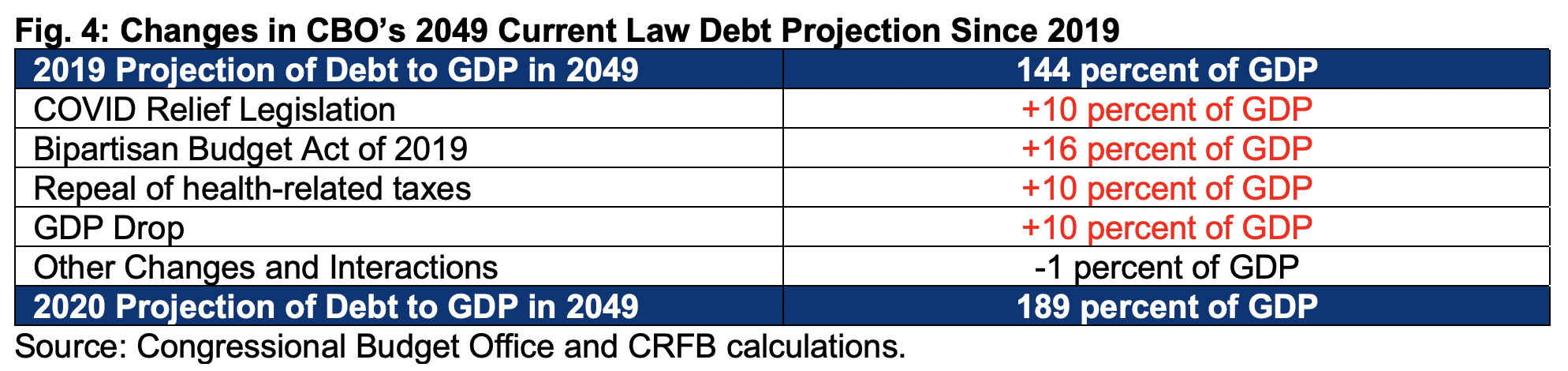

- The Long-Term Outlook is Worse Than Last Year’s Projections. CBO projects debt will reach 189 percent of GDP in 2049, almost one-third higher than the 144 percent of GDP in its 2019 projections. Higher debt is driven in large part by the COVID crisis and response, higher spending resulting from the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019, and lower revenue due to the repeal of various health-related taxes – especially the tax on high-cost insurance plans.

- High and Rising Debt Has Adverse and Potentially Dangerous Consequences. CBO estimates that national income will be $6,300 per person lower in 2050 as a result of debt rising from 2019 levels under current law. As we’ve written before, rising debt will also increase interest payments, place upward pressure on interest rates, weaken the ability to respond to the next recession or emergency, place an undue burden on future generations, and heighten the risk of a future fiscal crisis.

As CBO shows in its report, the longer policymakers wait to begin addressing the debt, the harder it will be. While the current focus should be on the COVID-19 crisis, policymakers must also work to get our long-term fiscal house in order.

Debt Will Nearly Double the Size of the Economy By 2050

CBO projects debt held by the public will rise from over 79 percent of the economy in 2019 and 98 percent by the end of 2020 to 195 percent of GDP by 2050, nearly 2.5 times the 2019 level. Projected debt in 2050 is nearly five times higher than the 50-year average of 42 percent of GDP and will be on track to double the previous record of 106 set just after World War II. In dollar terms, debt will rise from nearly $21 trillion today to $121 trillion by 2050.

Actual debt levels could grow significantly faster than CBO forecasts. Under our alternative scenario, which assumes policymakers enact another $1 trillion of fiscal support to address the current crisis, extend most expiring tax cuts, and grow appropriations with the economy rather than with inflation, debt would reach 246 percent of GDP in 2050.

Even under current law, high and rising debt represents a large fiscal gap. For example, CBO estimates policymakers would need to enact 3.6 percent of GDP in spending cuts and tax increases – starting in 2025 – in order to restore the debt to 2019 levels by 2050. That’s the equivalent of cutting all spending by one-sixth or increasing all revenue by one-fifth.

The longer policymakers wait to fix the debt, the harder and costlier it will get. That fiscal gap would grow to 4.4 percent of GDP if action was delayed until 2030, or 5.9 percent if delayed until 2035. Delaying action means the necessary changes will be spread among fewer people, policymakers will have less ability to carefully target adjustments, and ultimately it will be harder to phase in new policies or give families and businesses time to prepare and adjust for them.

Deficits Will Explode

Deficits have already risen dramatically from 2.4 percent of GDP ($442 billion) in 2015 to 4.6 percent of GDP ($984 billion) in 2019 and a COVID response-driven 16.0 percent of GDP ($3.3 trillion) this year. CBO expects deficits to recover from their recent spike but otherwise continue their upward trend, reaching 5.3 percent of GDP ($1.6 trillion) in 2030, 9.0 percent of GDP ($3.9 trillion) in 2040, and 12.6 percent of GDP ($7.8 trillion) in 2050.

CBO’s 2050 deficit projection of 12.6 percent of GDP would be higher than any time in modern history outside of World War II and the COVID-19 economic crisis, and is over four times the 50-year average of 3 percent of GDP.

Under current law, high deficits will grow with interest costs, despite relatively low interest rates. CBO projects primary deficits to grow to 3.1 percent of GDP in 2030, 4.1 percent in 2040, and 4.5 percent in 2050. They project interest costs will rise from 2.2 percent of GDP in 2030 to 4.9 percent in 2040 and 8.1 percent in 2050.

Deficits could be even higher if lawmakers continue their pre-COVID streak of fiscal irresponsibility. Under our alternative scenario that assumes policymakers enact an additional $1 trillion of fiscal support to combat the current crisis, extend most expiring tax cuts, and grow appropriations with the economy rather than with inflation, deficits would reach 16.5 percent of GDP in 2050. That’s higher than any time in modern history – including 2020 – other than the final three years of World War II; it is also more than five times the average over the last half-century.

Spending Growth Will Outpace Revenue

Rising debt and deficits are driven by a disconnect between spending and revenue. CBO expects spending to grow rapidly over the next three decades and revenue to grow gradually.

CBO projects spending will grow from 21.0 percent of GDP in 2019 to 31.2 percent of GDP by 2050 while revenue will grow from 16.3 percent to 18.6 percent of GDP. In the short term, spending will temporarily spike to 32.0 percent of GDP and revenue will fall to 16.0 percent as a result of the COVID-19 crisis – but these effects will quickly wane.

The projected long-term growth in spending is largely driven by rising health, interest, and retirement costs. CBO projects spending on Social Security and the major health care programs will rise from 10.2 percent of GDP in 2019 to 15.5 percent in 2050 while interest on the debt will grow from 1.8 percent of GDP in 2019 to 8.1 percent in 2050 (interest costs will actually be below 2019 levels through 2028 as a result of very low interest rates).

The 11.7 percent of GDP growth in Social Security, health, and interest costs explains more than the entire 10.3 percent growth in total spending through 2030. Meanwhile, revenue will only grow by 2.3 percent of GDP – failing to cover the rising cost.

Under our alternative scenario, spending and revenue would reach 34.0 and 17.4 percent of GDP, respectively, by 2050.

Rising health and retirement costs and insufficient funding also puts trust funds in danger. CBO estimates the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) will exhaust in FY 2021, the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund in FY 2024, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) in FY 2026, and Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) in calendar year 2031. On a combined basis, CBO estimates the Social Security trust funds will run out in calendar year 2031 and face a 75-year shortfall of 1.6 percent of GDP, or 4.7 percent of taxable payroll.

The Long-Term Outlook is Worse Than Last Year's Projections

CBO’s newest projections show significantly higher debt than last year’s projections in both the short and long term. Specifically, debt this year is projected to be 19 percentage points higher than the previous projection, debt in 2030 is projected to be 16 points higher, and debt in 2049 is projected to be 45 points higher – 189 percent of GDP in 2049, compared to 144 percent.

By our estimates, less than a quarter of the increase is due to legislation enacted to combat the COVID pandemic and resulting recession, which is largely one-time spending. Those measures (which we are tracking at COVIDMoneyTracker.org) are projected to add 11 percent of GDP of debt this year, holding steady at about 10 percent of GDP by 2049.

About half of the deterioration is due to two pieces of legislation enacted in 2019. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA19) – which lifted discretionary spending caps in 2020 and 2021 and thus increased CBO’s discretionary projections in future years – is responsible for increasing the debt by 16 percent of GDP. The repeal of three health care taxes at the end of 2019, particularly the “Cadillac tax” on high-cost insurance plans, increased debt by 10 percent of GDP.

Lower projected output and price levels also reduce the denominator against which debt-to-GDP is measured. In 2049, CBO projects GDP will be about 7 percent lower than it did last year. This alone is responsible for a 10-percentage point increase in debt-to-GDP.

Other economic and technical changes roughly cancel each other. Due in large part to the current crisis, CBO now projects lower economic output, income, price levels, and interest rates than previously. These changes reduce spending on Social Security, health care and interest, but increase spending in other areas (for example, unemployment benefits) and reduce revenue.

Total deficits in 2049 are projected to be 3.5 percent of GDP higher than in last year’s outlook – 12.2 percent as opposed to 8.7 percent.

The majority of this increase, 2.0 percent of GDP, is from interest costs that mainly stem from larger debt. Lower revenue contributes an additional 0.9 percent and higher discretionary spending an additional 0.5 percent.

High and Rising Debt Has Adverse and Potentially Dangerous Consequences

While the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis necessitated short-term borrowing to mitigate economic damage and spread costs over time, CBO warns that high and rising debt will have adverse and potentially dangerous consequences if allowed to grow continuously at its current pace.

In normal times, when the economy is operating near its potential and the Federal Reserve is no longer buying large quantities of long-term debt, increased federal borrowing tends to crowd out private investment. This leads to fewer buildings, machinery, and equipment, as well as fewer new ventures and technologies, which in turn depresses worker productivity and slows income growth.

CBO estimates that the economy will grow about 0.2 percentage points per year slower under current law as compared to a scenario where debt was restored to 2019 levels – 79 percent of GDP – by 2050. Under CBO’s baseline, Gross National Product (GNP) will be more than 6 percent lower in 2050 – the equivalent of $6,300 per person per year – if debt is allowed to rise from 2019 levels as under current law.

High and rising debt also puts upward pressure on interest rates – which are low in spite of, not because of, high debt. CBO estimates the rate on ten-year Treasury securities will rise from 0.7 percent today to 4.8 percent by 2050. Many factors drive this increase, including the continued accumulation of federal debt.

Rising debt and interest rates mean rapid growth in interest payments. Under current law, CBO projects interest payments to rise from 1.6 percent of GDP in 2020 up to 8.1 percent of GDP by 2050. High levels of debt mean that even small increases in interest rates could result in substantially higher interest payments. For example, if interest rates were just 1 percent higher than projected, net interest costs would be 15 percent of GDP by 2050. Each dollar spent on interest is unavailable for other priorities.

CBO also notes that high and rising debt increases the risk of a fiscal crisis, which CBO describes as “a situation in which investors lose confidence in the U.S. government’s ability to service and repay its debt, causing interest rates to increase abruptly, inflation to spiral upward, or other disruptions.”

They also point to other possible disruptions and dangers of debt, including higher inflation expectations, greater difficulty financing activity in international markets, or less willingness to borrow for a national emergency or crisis.

Conclusion

CBO continues to remind us what we’ve known for years but have chosen to ignore: the federal budget is on an unsustainable course, particularly over the long-term. CBO’s latest long-term baseline shows the budget outlook will deteriorate in the coming decades as a result of irresponsible tax and spending policies and the growth of health and retirement spending. Moreover, the response to the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis, while necessary to stabilize the economy and address the pandemic, has greatly increased long-term projections of debt and deficits.

Under current law, debt will grow nearly 2.5 times over the next three decades, from over 79 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2019 to 195 percent by 2050. Deficits will reach 12.6 percent of GDP in 2050, higher than any other time in post-WWII history besides this year.

High and rising debt will have serious, adverse consequences. CBO estimates per-person income will be $6,300 less by 2050 under current law, compared to a scenario in which debt is stabilized at 2019 levels. Furthermore, as we’ve previously written, rising debt also increases interest payments, places upward pressure on interest rates, weakens our ability to respond to the next recession or emergency, places an undue burden on future generations, and heightens the risk of a fiscal crisis.

Unfortunately, the actual fiscal situation could turn out to be even worse than CBO projects. Under our alternative scenario, which assumes additional COVID relief is enacted, tax cuts are continued, and appropriations grow with the economy, deficits will reach 16.6 percent of GDP by 2050 and debt will rise to 245 percent.

CBO estimates stabilizing debt at 2019 levels would require annual tax and spending adjustments between 2025 and 2050 equivalent to 3.6 percent of GDP. A carefully crafted package could be phased in gradually, targeted to ask the most from those who can best afford it, and designed to improve economic growth and thus reduce the burden of any adjustments. However, there is no magic wand we can wave to fix these problems

While policymakers should prioritize addressing the current pandemic and economic crisis, they cannot and should not continue to ignore our dangerous long-term fiscal situation.

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image