The Tax Break-Down: Child Tax Credit

This is the fourth post in our blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which will analyze and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform.

The child tax credit (CTC) is a flat-dollar tax benefit offered to most households to help offset the cost of children. It has been in the tax code since 1997, and was significantly expanded under President Bush in 2001 and President Obama in 2009. Today, the credit covers almost 60 million children and 35 million families. Many other OECD countries offer a child tax credit, either to all families or to those below a certain minimum income.

The credit allows taxpayers to reduce the amount of taxes they owe by $1,000 per child age 17 and under. For example, a two-child family owing $5,000 before the credit would owe only $3,000 after the credit. Currently, the credit is partially refundable for households that don’t have any tax liability – meaning the IRS will send those families a check. Specifically, a household can receive a refund up to 15 percent of income above $3,000. After 2017, the refundability threshold will increase from $3,000 to approximately $13,200. Alternatively, families with at least three children can get a refund up to their entire payroll tax liability not already offset by the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The CTC currently phases out starting at $75,000/$110,000 (individuals/couples). A two-child family would lose the credit entirely at $115,000/$150,000 of income.

The CTC was originally enacted as a part of the balanced budget agreement of 1997 as a nonrefundable $400 credit. It was raised to $500 in 1999 and increased to $1,000 and made partially refundable in 2001. In the 2009 stimulus act, the CTC’s refundability was expanded significantly on a temporary basis. This expanded refundability was extended for two years in 2010 and further extended through 2017 at the beginning of this year.

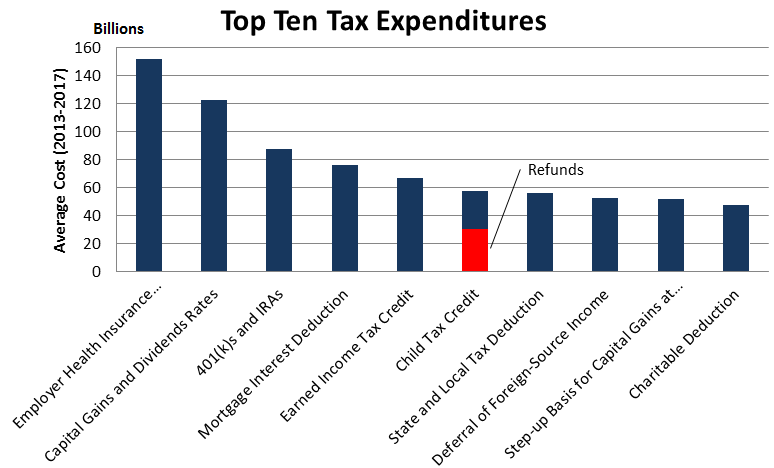

How Much Does It Cost?

The child tax credit is the sixth largest tax break today, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). It costs $57 billion in revenue this year, $290 billion over 5 years, and an estimated $550 over ten years. Of that total, slightly more than half is spent on refunds to taxpayers who have no tax liability. OMB estimates a smaller figure: the credit cost $47 billion in 2012.

If the current provisions were extended permanently instead of expiring in 2017, the CTC would cost an additional $12 billion per year starting in 2018, or more than $600 billion total over the next decade.

The Tax Foundation estimates that if the Child Tax Credit was eliminated and the revenue was used to reduce rates, all tax rates could decrease by 4.8 percent (so the top 39.6 bracket would become 37.7 percent).

Who Does It Affect?

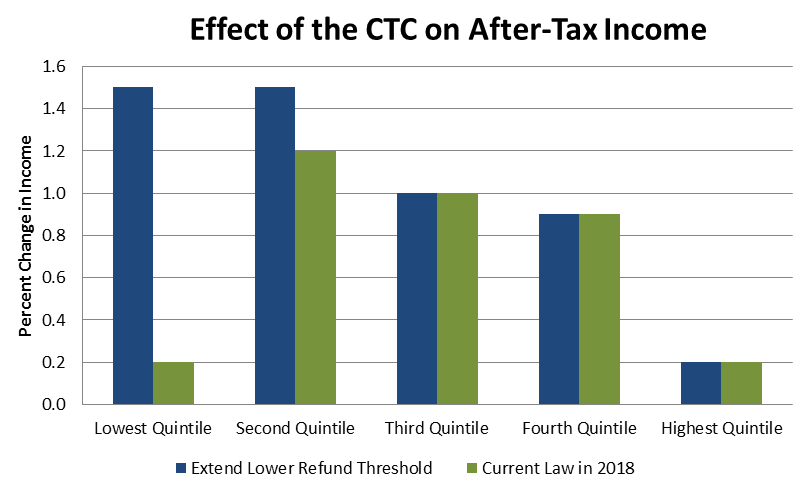

As opposed to some of the other tax breaks we’ve profiled, the child tax credit is relatively progressive, particularly in its current form. It boosts after-tax incomes for the bottom 40 percent of taxpayers by 1.5 percent. Since it provides a flat per-child benefit, an upper-income household sees a smaller percentage change in income. The top fifth of taxpayers only see a 0.2 percent increase in after-tax income. Because of income phase-outs, the top 1 percent generally do not benefit from the child tax credit.

Much of the credit’s progressivity comes from the law’s 2009 expansion to provide greater refunds to low-income households. If the expansion expires as scheduled at the end of 2017, taxpayers in the bottom quintile would lose most of their benefit, though those in the second quintile would retain much of their benefit and taxpayers in the top 60 percent would see no change.

In terms of the distribution of the benefit of the child tax credit, more than three quarters of the benefit goes to the bottom sixty percent of the income spectrum, including about 22 percent to the bottom quintile and almost 30 percent accruing to the second quintile. The wealthiest fifth of taxpayers receive less than 5 percent of the benefit.

What are the Arguments For and Against the Child Tax Credit?

Proponents of keeping or expanding the child tax credit argue that a family should be held harmless for the costs of having children, an equity goal the credit helps to achieve (though some argue it does not do enough and some argue it already overcompensates). Some suggest the credit accomplishes a laudable and fiscally important goal by encouraging people to have more children. Finally, proponents argue that the child tax credit, along with the earned income tax credit, provides crucial support for low-income families. According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, the Child Tax Credit and EITC lifted more than 9 million people, including 4.9 million children, out of poverty. They continue by pointing out each dollar of income earned through tax credits improves children’s school performance and increases future incomes by more than a dollar.

Opponents of the child tax credit argue that children should not be subsidized by the government and such favoritism in the tax code is inappropriate. According to this argument, the decision to have children is a parent’s choice on how to consume income, and therefore should not be favored under an income tax. The phase-out of the refundable portion adds 5 percent to the marginal tax rates of households above $75,000/$110,000 of income, which can disincentivize work. Opponents also argue the credit is wrought with fraud, often pointing to a 2011 Treasury Inspector General report that describes how $4.2 billion in child tax credits were refunded to individuals who were not authorized to work in the United States, but allowed to claim the credit under current law. Furthermore, some anti-poverty advocates argue that the $57 billion annual cost could be much better targeted, since much of the child tax credit (particularly at 2018 levels) goes to middle-class rather than poor families.

What are the Options for Reform?

A number of options exist to reform the existing Child Tax Credit. The President’s Budget plans for the CTC low-income expansions to be extended past 2017, which would cost almost $65 billion.

Because there are many overlapping tax incentives for children, including the dependent exemption, deduction for child care expenses, EITC, and exclusion for employer-provided child care, several tax reform plans (described below) consolidate and simplify these incentives into a single, larger child credit.

The credit could also be reduced in a number of ways. Complete repeal would raise more than $500 billion, enough revenue to lower tax rates by 4.8 percent. The credit could be reduced back to 2001 levels of $500, with a $10,000 refund threshold that rises with inflation, eliminating much of the benefit to low-income families.

A number of options make smaller CTC changes. Senator Ayotte proposed a bill this year to require taxpayers claiming the credit to include their Social Security numbers, effectively banning illegal immigrants from claiming the credit, even if their children are U.S. citizens. Options to simplify the credit’s definitions and calculations also raise small amounts of revenue.

The below table measures the cost of each option against current law, and against current policy, which assumes the child tax credit is extended at current levels past 2017.

| Ten-Year Revenue from Reform Options on the Child Tax Credit (billions) | ||

| Policy | Current Law | Current Policy |

| Extend current law refundability past 2017 | -$65 | $0 |

| Repeal Child Tax Credit | $505 | $570 |

| Make Child Tax Credit Non-refundable | $210 | $275 |

| Revert Child Tax Credit to pre-Bush era levels of $500/child, raising the refund threshold to $13,200 and indexing it to inflation | $375 | $440 |

| Lower eligibility age to 13 and younger | $100 | $115 |

| Require taxpayers to include their Social Security Number when claiming refundable credits for their children | $25 | $30 |

| Establish a single definition of children as below 19 for CTC, EITC, and Dependent Exemption | $20 | $25 |

| Restrict the refundable portion of the CTC and the EITC to taxpayers with less than $1,650 of investment income | $10 | $10 |

| Reduce computational complexity for CTC | $5 | $5 |

| Make the Child Tax Credit fully refundable, regardless of earnings | -$110 | -$45 |

| Repeal income phase-out for high-income taxpayers | -$110 | -$110 |

What Have Tax Reform Plans Done With It?

Most tax reform plans retain support for children, either through the child tax credit or other means. Many use tax reform as an opportunity to simplify and combine provisions regarding children. The Fiscal Commission’s illustrative tax reform plan eliminated most tax expenditures, but retained the child tax credit to enhance the code’s progressivity, as did the Wyden-Coats tax reform legislation. The Domenici-Rivlin plan combined the standard deduction, personal exemptions, CTC, and EITC into separate work and family credits (the family credit being larger than the current CTC), an approach also taken by tax reform advisory panels in 2005 and 2010. The Center for American Progress combines the credit and the dependent exemption into a new $1,600 child tax credit (along with a $600 credit for non-child dependents) while raising the income phase-out from $75,000 to $200,000. The Economic Policy Institute would make the credit fully refundable.

Where Can I Read More?

- Congressional Research Service – The Child Tax Credit

- Center for Budget and Policy Priorities – Policy Basics: the Child Tax Credit

- Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration - Individuals Who Are Not Authorized to Work in the United States Were Paid $4.2 Billion in Refundable Credits

- Urban Institute - Tax Simplification: Clarifying Work, Child, and Education Incentives

- Tax Foundation – Case Study #9: Child Tax Credit

- Center for American Progress – Separating Fact from Fiction About the Child Tax Credit

- American Enterprise Institute – Raising kids? Your taxes are far too high

*****

The child tax credit is one of the most widely-used tax breaks in the code today. It is available to nearly all taxpayers with children, is retained by most published tax reform plans, and is an important driver of the current progressivity of the code. Although Congress may not wish to remove this provision, they should remain open to reforming it. The tax code currently subsidizes family and children in a number of different ways, leading to unnecessary complexity. The child tax credit costs over half a trillion dollars over ten years and the dependent exemption (which is a NTEBP, not a tax expenditure) costs another half trillion. Tax reform represents an opportunity to simplify these provisions, curb abuse, and in the process can provide revenue to cut rates or reduce the deficit.

See other posts in The Tax Break-Down here. We've written about the State & Local Tax Deduction, Last-in-First-Out (LIFO) Accounting rules, and the preferential rates for capital gains.

Note: This post was updated on August 30 to correct typos regarding the President's policy and the scores for certain options, and to clarify the credit's phase-out range and use by non-citizens.