President’s Budget Calls for Record Low Discretionary Spending, Record High Revenue

As we showed last week, OMB projections show the President's budget will put the debt on a downward path this decade with deficits below 2 percent of GDP toward the end of the decade. This is true despite an aging population, growing health care costs, almost no changes to Medicaid and Social Security, and real but modest reductions to Medicare.

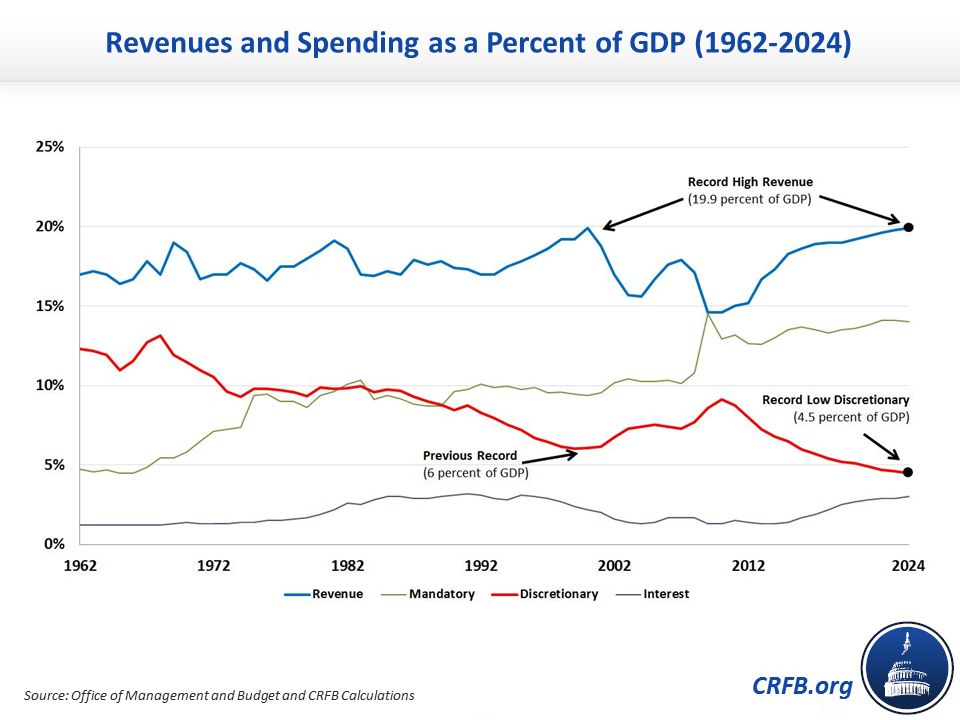

So how does the President's budget keep deficits at manageable levels despite continued growth of entitlement programs? Essentially, he allows discretionary spending as a share of GDP to fall to historic lows, and revenue to rise to historic highs.

Under the President's budget, the combination of the economic recovery, new taxes from the Affordable Care Act and Fiscal Cliff deal, increased revenue from real "bracket creep," over $1 trillion in net tax increases, and over $450 billion of additional revenue from immigration reform will lead revenue to rise from 17.3 of GDP in 2014 to 19.9 percent by 2024. This matches the previous record set in 2000, when an economic boom and stock market bubble helped bring revenues up to 19.9 percent of GDP.

Meanwhile, the discretionary reductions from the Budget Control Act, the drawdown in war spending, and the President's proposal to replace sequestration with a discretionary path that moves spending near to post-sequester levels by the end of the decade put downward pressure on discretionary spending as a share of GDP. In total, discretionary spending will fall from 6.8 percent of GDP in 2014 to 4.5 percent in 2024, the lowest is has been since before World War II.

Importantly, these discretionary reductions are occurring both on the defense and non-defense side. Total defense spending (including on the wars) under the President's budget is slated to fall from 3.5 percent of GDP in 2014 to 2.8 percent by 2024. By comparison, defense spending has averaged 4.5 percent over the past four decades, and has not been less than 3 percent since 2001. Meanwhile, non-defense spending—which includes everything from education to the National Park Service to the State Department to the federal workforce—is projected to fall from 3.2 percent of GDP in 2014 to 2.3 percent by 2024, which would be the lowest level on record. Over the last 40 years, non-defense spending has averaged 3.8 percent of GDP.

Many analysts and policymakers on both sides of the aisle have questioned the desirability and sustainability of allowing discretionary spending to fall so low or revenues rise so high. Yet in the final analysis, these changes highlight the consequences of failing to address the growth of our entitlement programs.

Had policymakers begun work to make Social Security and Medicare more secure at the beginning of this century, record-high revenues and record-low discretionary levels might not be necessary to put the debt on a more sustainable path. And even today, failure to address growing entitlement programs inevitably requires revenue and discretionary spending to be a greater contributor to debt stabilization.

This is not to say that discretionary reductions and revenue should not represent part of the solution—we've written many times before that they will have to be. But policymakers must recognize the inherent trade-offs. Without structural entitlement reforms that truly slow the growth of our health and retirement programs, discretionary programs will keep shrinking, tax burdens will keep rising, and it is unlikely we will be able to address our long-term debt growth.