New York Times Article Does More to Perpetuate Myths than to Dispel Them

With Social Security’s 90th birthday approaching, The New York Times (NYT) published an article this week alleging “6 myths about it that won’t go away." Unfortunately, the article does more to perpetuate many myths than it does to dispel them.

With the Social Security retirement program only seven years away from insolvency, it’s important to get the facts straight. Below, we correct the record on Social Security’s “myths” and the real danger that the program’s financing faces.

Alleged Myth 1: Social Security is ‘running out of money’

Fact: Social Security’s trust fund is running out of money – and soon

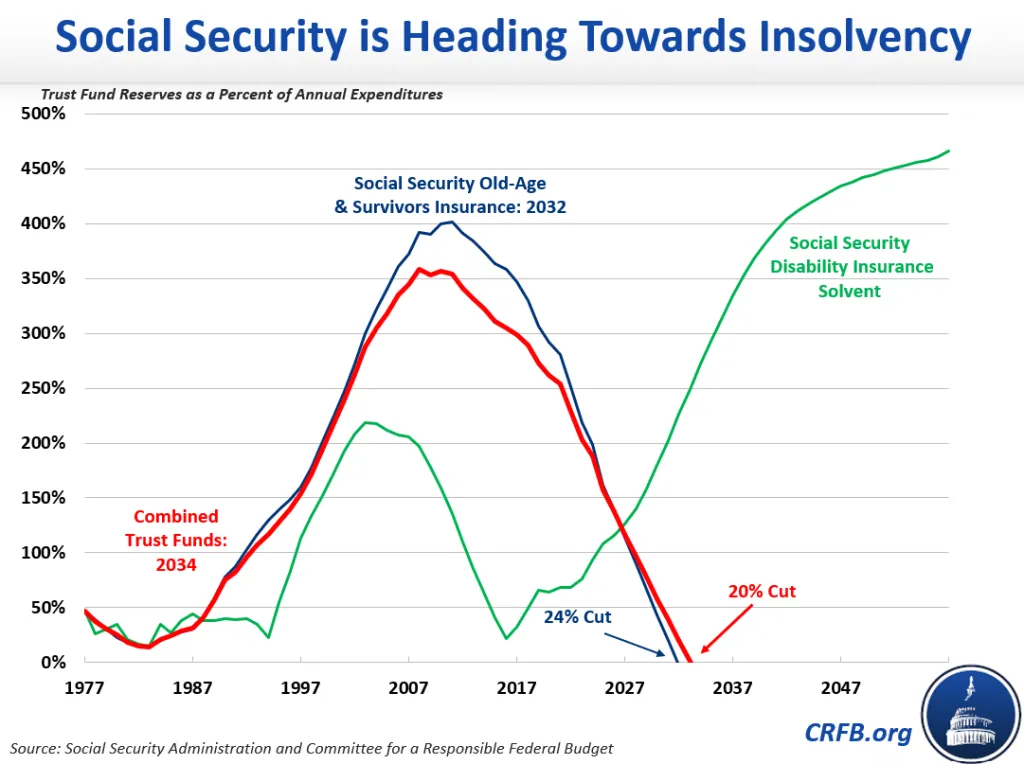

Though the NYT describes the claim that Social Security is running out as a “myth,” it rightly points out that Social Security has been “drawing down the program’s reserves” as costs continue to exceed revenue. By 2032 (2033 prior to OBBBA), the trust fund for the retirement program (Old-Age and Survivors Insurance, or OASI) will be empty; its reserves will have “run out.” At that point, the law calls for benefit payments to be limited to incoming revenues – which means a 24 percent across-the-board cut to all beneficiaries – the equivalent of about $18,000 in annual benefits for a dual-earner retiring couple in that year.

There is no myth here – the program’s trust fund is on course to depletion, and policymakers will need to affirmatively act to avoid this large, abrupt benefit cut in just seven years.

Alleged Myth 2: Aging boomers are the problem

Fact: Social Security’s shortfall is driven mainly by population aging

About 60 million seniors collect Social Security benefits today, up from less than 50 million a decade ago, 40 million in 2000, and 30 million in 1980. Those over 65 now represent 18 percent of the population compared to about 11 percent in 1980. And with over 10,000 Americans retiring every day, the Social Security rolls will continue to grow.

There is no question that the aging of the population – including the retirement of the baby boomers – is a key driver of Social Security costs. The NYT itself acknowledges that “an aging population has accelerated the drawdown of the trust fund.”

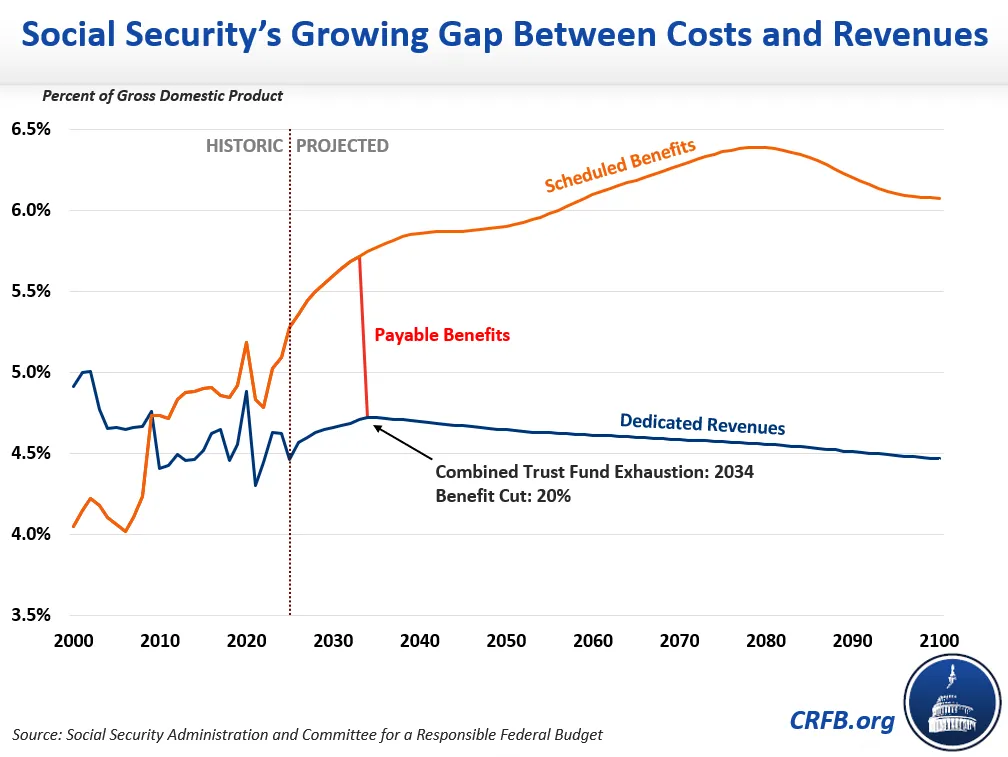

It is true, as the article states, that rising inequality and slow birth rates have contributed to Social Security’s revenue collection dipping from 5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1990 to 4.5 percent in 2024. But the aging of the population has driven costs from 4.2 percent of GDP to 5.3 percent over the same period – and is projected to continue driving up costs to 5.9 percent by 2050.

The NYT describes population aging as a myth because it “was always anticipated.” But the fact that lawmakers have known about this problem for over 40 years and done nothing to solve it does not make its existence a myth.

Alleged Myth 3: Social Security helps drive the deficit

Fact: Social Security is currently adding to the unified budget deficit and may add much more in the future

The NYT rightly explains that Social Security is financed largely by payroll taxes and other dedicated revenue and that its trust fund is not allowed to borrow under current law – but that doesn’t mean it can’t add to annual deficits.

First, it is important to understand the difference between “on-budget” deficits that exclude Social Security and the postal service and “unified” budget deficits, which include everything. Almost all discussion in Washington centers around the unified budget deficit, and Social Security can both add to and subtract from that measure.

Between 1990 and 2010, for example, Social Security’s revenue exceeded its costs by $1.1 trillion – reducing the overall budget deficit.1 Since then, costs have exceeded revenue by a combined $1.4 trillion, adding to deficits. This year, Social Security’s cash imbalance will add a projected $250 billion to the deficit.

Generally speaking, Social Security’s contributions to the deficit cannot exceed previous subtractions from the deficit under the law – though there are some exceptions related to one-time general revenue transfers such as the payroll tax holiday of 2011 and 2012 and inappropriate interest rate differentials. But it is nonetheless adding to the deficit today.

The NYT does correctly point out that, under current law, Social Security cannot borrow from general revenue to fund benefits after it is insolvent. Ironically, the same article floats the idea “to inject general revenue to keep benefits whole,” which would mean doing just that.

Alleged Myth 4: The trust fund is nothing but a pile of I.O.U.s

Fact: The trust fund represents a real obligation, but is not backed by assets

The trust fund reserves represent an obligation of the federal government, which is in a way a form of I.O.U. It is the same type of I.O.U. that a bond represents: a promise to repay the principal, with interest, later. It is almost certain to be paid back in its entirety, and in fact, for the last 15 years, the government has already been paying the trust funds for bonds it redeems. Unlike corporate bonds or stocks, however, these are not backed by private sector assets. And unlike other federal debt, the trust fund bonds are not traded on the private market. Because they represent a debit to one part of government and a credit to another, the trust fund holdings are in many ways an accounting mechanism to ensure past payroll tax collection allows for future benefit payments – they are not the same as the appreciating private assets one might see in a pension, mutual fund, or retirement account.

Alleged Myth 5: We need to cut benefits now to pay them later

Fact: Acting now with thoughtful benefit and revenue reforms is the best way to ensure benefits can be paid in full

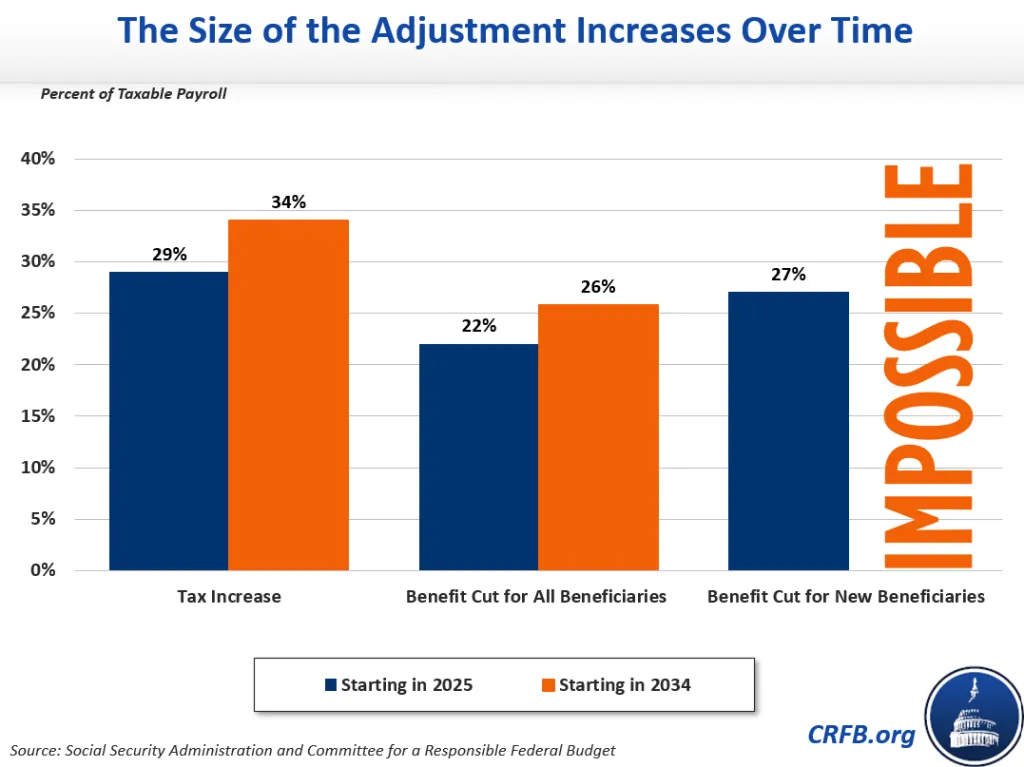

Under current law, Social Security beneficiaries face a 24 percent across-the-board benefit cut in just seven years. Avoiding this cut will require closing Social Security’s imbalance – which means reducing its costs (benefit payments), increasing its dedicated revenue, or some combination of the two. (Our Social Security Reformer allows users to design their own solvency plan.)

The NYT is right that we don’t need to cut benefits now to pay them later. But any fix to Social Security is likely to be bipartisan, and based on historical experiences and efforts, the fix will likely include some combination of benefit and revenue changes.

Acting sooner will literally reduce the necessary size of the adjustment. As an example, the program's Trustees estimate solvency could be restored with a 22 percent cut to benefits starting today, rising to 26 percent if beginning in 2034 when the theoretically combined trust funds are scheduled to go insolvent. And acting today allows policymakers to phase in policies gradually, target policies more thoughtfully, and give workers the time to plan and adjust.

Alleged Myth 6: Waste, fraud, and abuse abound

Fact: Fraud and abuse are indeed small in Social Security

Of the six alleged myths in the article, this is the only actual myth. Social Security has a less than 1 percent overpayment rate – among the lowest in the federal government. There is always room for improvement, especially when it comes to the disability program, but fraud and abuse are rare in the Social Security program – certainly not large enough to make a significant difference in the program’s finances.

* * *

Social Security is just seven years from insolvency and is desperately in need of a rescue plan. The first step is for politicians, experts, and the media to start telling the truth when it comes to Social Security’s challenges. We don’t need more articles that create more myths than they bust.

1 All dollar estimates in this paragraph are from cash balances for OASDI non-interest income and cost rates calculated from the 2025 Trustees Report, Table IV.B1. Rates as a percent of taxable payroll converted to cash by multiplying by taxable payroll in Table VI.G6.