IRA Energy Provisions Could Cost Two-Thirds More Than Originally Estimated

At the time of its passage, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) would spend roughly $400 billion through Fiscal Year (FY) 2031 on energy and climate-related provisions, primarily composed of tax credits. Based on new JCT scores, the energy provisions' projected costs have risen by about two-thirds, to $660 billion through 2031 and to $790 billion through 2033.1

Since enactment, JCT – which provides scores for tax legislation – has increased its estimate of the IRA's climate and energy tax credits significantly. These increases are due to a combination of higher inflation, greater demand for and interest in subsidized activities, looser-than-expected regulations, and other factors. Because CBO and JCT have not re-estimated the offsets, it is not clear whether a full re-estimate of the IRA would show reduced or increased budget deficits, though it would likely be close to budget-neutral.

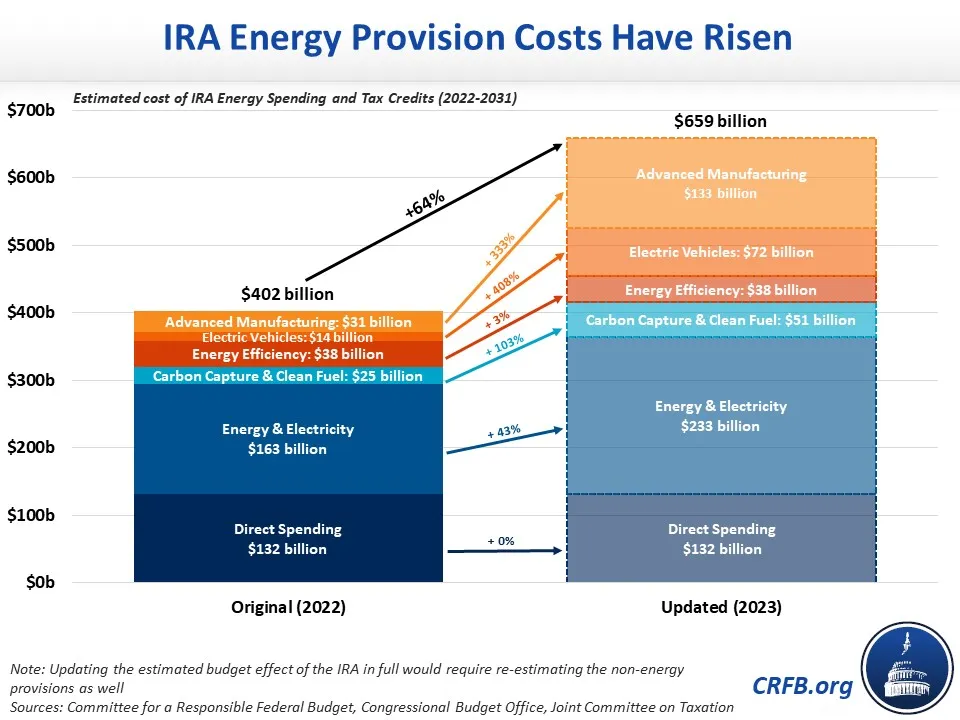

The IRA included a combination of new revenue, prescription drug savings, health spending, and energy and climate provisions. The energy and climate provisions were originally estimated to cost roughly $400 billion through 2031, including $132 billion of direct spending, $163 billion for energy and electricity, $25 billion for carbon capture and clean fuels, $38 billion for energy efficiency, $14 billion for electric vehicles, and $31 billion for advanced manufacturing.

Since that original score, projections of total costs are roughly two-thirds higher, or 50 percent higher after adjusting for inflation. While direct spending was mostly capped nominally, and therefore unchanged, the cost of the energy and climate tax credits have roughly doubled on a nominal basis.

In particular, the electric vehicle (EV) tax credits are now projected to cost five times as much as originally scored through 2031 ($14 billion to $72 billion), the advanced manufacturing credits are projected to cost over four times as much ($31 billion to $133 billion), and the carbon capture and clean fuel credits are projected to cost twice as much ($25 billion to $51 billion). These credits explain more than two-thirds of the total growth in the cost of the energy provisions. JCT also expects the energy and electricity credits to be 43 percent larger – rising from $163 billion to $233 billion.

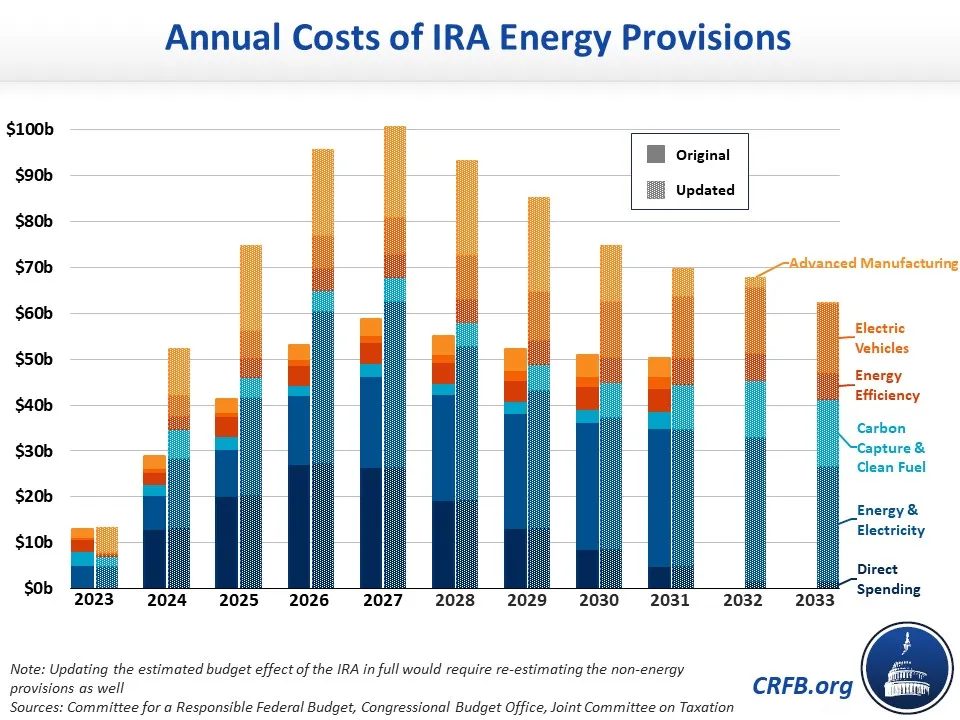

Some of this increase stems from an earlier assumed use of IRA tax credits, with energy provision costs expected to be more than 80 percent higher from 2024 through 2026 but about 40 percent larger in 2031.

Although higher than originally scored, these new projections are much lower than those from some outside organizations. For example, Goldman Sachs recently released a report suggesting energy provision costs had tripled. Goldman’s figures were likely considerably overstated, as they compared different budget windows (through Calendar Year 2032 instead of FY 2031), assumed very rapid green adoption (for example, that U.S. electric vehicle sales will comprise 70 percent of new cars by 2030 and 98 percent by 2035), and do not appear to account for certain interactions with the tax code.

Claims that the IRA was actually “deficit-increasing” are also premature, as only one part of the IRA has been re-estimated. The $256 billion higher price alone would more than consume the $238 billion of scored deficit reduction; however, higher inflation and recent corporate behavior suggest that the IRA’s taxes and offsets will also grow in magnitude. On net, the legislation is likely close to budget-neutral in the first decade – though significant uncertainty remains – and deficit-reducing over time, assuming the tax credits phase out as intended.

Still, lawmakers should act wherever possible to reduce the IRA’s price tag. Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), a key figure in drafting the IRA, has identified several areas where he argues the Treasury Department’s regulations for the new clean vehicle tax credit are much looser than intended or allowed under the legislation. One is the establishment of a “50 percent of value-added test” that treats extraction and processing separately. This relaxes what the law prescribed for determining if the IRA’s EV battery critical minerals requirement is met. Another allows “constituent materials” to be included as part of the value added for critical minerals. A third regulation adopts an expansive definition of a free trade agreement for determining which foreign countries can be involved in the EV production process. Adjusting these rules to more closely match the JCT's original interpretation of the IRA, either through the regulatory process or codifying legislation, could help to reduce energy provision costs. So too would closing various loopholes as they arise, such as the one counting leased electric vehicles as commercial rather than personal vehicles to gain eligibility for a larger tax credit.

Lawmakers could also consider incorporating caps or triggers that phase down or adjust some of the credits based on cost, usage, or emissions outcomes. Such caps and triggers previously applied to the electric vehicle tax credits prior to the IRA and will apply to the new clean electricity production and investment tax credits starting in 2032.

Overall, while the IRA has the potential to improve the country’s long-run fiscal outlook, the substantial growth in the expected cost of its energy provisions is cause for concern. Policymakers should act to mitigate these costs overruns to prevent an already challenging fiscal trajectory from becoming even worse.

1 This estimate is derived by combining CBO’s initial score of the IRA’s capped spending provisions with JCT’s estimate of repealing most of the IRA's tax credit provisions under the Limit, Save, Grow Act, JCT’s score of amendments to repeal certain provisions, and JCT’s most recent score of ending the expansion of the electric vehicle credits under the Build It In America Act.

Note (7/10/2023): This piece has been updated to clarify the source of the changes to the estimates.