Five Ways to Improve the House COVID Relief Package

Recently, we put forward our principles for responsible COVID relief. The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan currently under consideration in the House includes a number of important policies to help end the pandemic, provide much-needed relief to struggling households, and support a strong economic recovery. Unfortunately, it falls short on many of our principles — it is much larger than the needs of the economy, much of its spending is poorly targeted, it includes a number of measures unrelated to the COVID pandemic and economic crisis, and it would abruptly cut off aid to unemployed workers at the end of August (see our summary here).

Fortunately, policymakers in the House and Senate still have an opportunity to address these concerns. The following adjustments would dramatically improve the composition of the package and ensure sufficient COVID relief is enacted at a net cost of about $1.3 trillion. We believe additional reforms could easily reduce the size of the package further to about $1.1 trillion.

In this piece, we suggest that policymakers:

- Remove or offset unrelated policies.

- Right-size state and local aid to match need.

- Better target rebates based on need.

- Extend and taper expanded unemployment benefits.

- Establish triggers so aid matches needs of the economy.

#1: Remove or Offset Unrelated Policies

By our estimates, the House COVID relief package includes at least $312 billion of policies that have little to do with the current crisis and were long-standing priorities prior to the pandemic. Among the unrelated provisions are a pension bailout; expansions of the Child Tax Credit (CTC), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the child care tax credit; an increase in the minimum wage to $15 an hour; and Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansions. Many of these are worthwhile policies that policymakers should consider making permanent parts of the tax code or budget. However, they were all developed long before the COVID crisis and not in response to it. They should be subject to normal pay-as-you-go rules, which means each policy should either be fully offset with new revenue or spending reductions to cover its cost.

For example, policymakers could offset these policies by restoring the 39.6 percent individual income tax rate for high earners, raising the corporate income tax rate, and/or limiting the growth of drug prices. These and other offsets were proposed by President Biden during the 2020 presidential campaign.

| Policy | Cost/Savings (-) |

|---|---|

| Expand Child Tax Credit from $2,000 to $3,000 ($3,600 for children under age 6) and make it fully refundable for one year | $110 billion |

| Expand Earned Income Tax Credit to childless adults for one year, tripling the credit, and include those aged 19-24 and over 65. Permanently allow recipients to have more investment income and expand the EITC in territories | $23 billion |

| Expand Child Care and Dependent Care Tax Credit to $4,000 ($8,000 for 2 or more children) for one year | $8 billion |

| Provide grants to multi-employer pension plans and change single-employer pension funding rules | $58 billion |

| Increase federal minimum wage to $15/hour by 2025 | $54 billion |

| Expand Affordable Care Act subsidies by reducing the maximum cost of insurance plans | $34 billion |

| Increase base Medicaid match to states that newly expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act | $16 billion |

| Allow states to expand Medicaid coverage for prisoners close to release and for pregnant and postpartum women for 5 years | $9 billion |

| Total, Policies Not Directly Related to the COVID Crisis | $312 billion |

| Potential Offsets | Cost/Savings (-) |

| Restore the top individual income tax rate to 39.6 percent | -$135 billion |

| Raise the corporate income tax rate | -$100 billion per 1% increase |

| Cap Medicare Part B and D drug price growth at the rate of inflation | -$80 billion |

Source: Congressional Budget Office and CRFB estimates of Biden offsets. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

#2: Right-Size State and Local Aid to Match Need

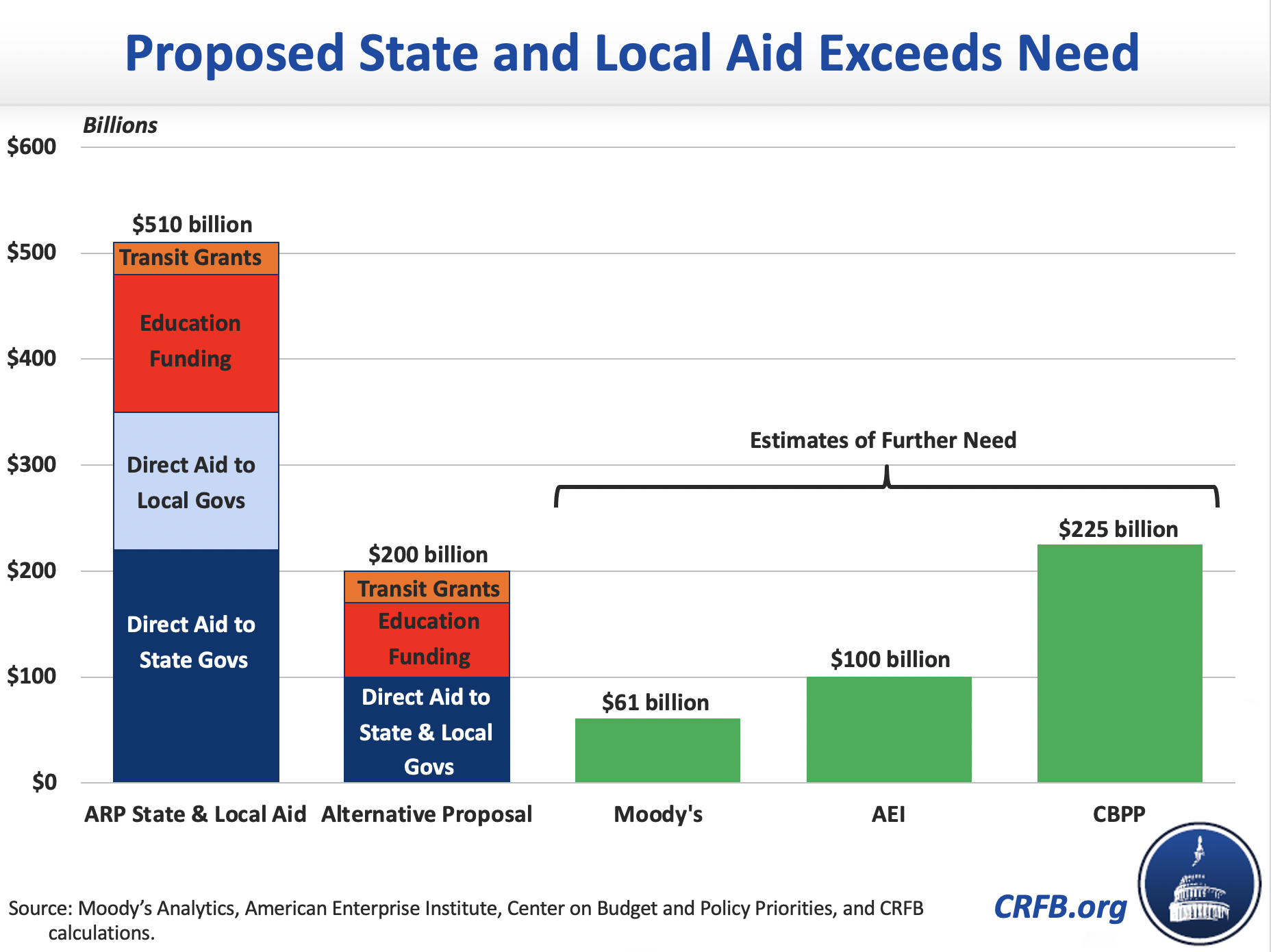

Between direct aid ($350 billion) and support for public schools ($130 billion) and transit programs ($30 billion), the House bill includes over $500 billion of aid to state and local governments. With many states now facing budget surpluses or strong revenue gains and others experiencing fewer losses than expected, this funding appears to be excessive. We recently showed that total state and local revenue has largely recovered and that needed aid is likely a fraction of what has been proposed.

We suggest policymakers reduce total aid to roughly $200 billion by shrinking direct aid to $100 billion and aid to public schools to $70 billion. The $100 billion of direct aid would be enough to cover states' revenue losses, based on estimates from Moody's Analytics and the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). The school aid reflects how much the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates would be spent through the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2023.

#3: Better Target Rebates Based on Need

The House package would issue a third round of Economic Impact Payments of $1,400 per eligible adult, child, and dependent. These rebates would phase out between $75,000 and $100,000 of individual income and $150,000 and $200,000 of family income. Under this proposal a family of five that made $130,000 in 2019 and saw its income rise to $150,000 in 2020 would receive $7,000 of additional rebates on top of the $3,000 received in January and $3,900 received last Spring. If the legislation retains expanded child and child care tax credits, a typical family of five would end up with at least $19,000 and as much as $28,000 in tax credits this tax year (compared to a maximum of just over $8,000 prior to the pandemic). Policymakers should better target these rebates — by pegging them to income loss between 2019 and 2020, by reducing the income level where rebates begin to phase out, and/or by integrating the child recovery rebate with the child tax credit. Relatively modest targeting could reduce the cost of rebates by $50 billion, while aggressive targeting could reduce their cost by $100 billion or more.

| Option | Total Cost | Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Phase out rebates from $150,000 to $200,000 for joint filers ($75,000 to $100,000 for singles) | $425 billion | $0 |

| Phase out rebates from $100,000 to $150,000 for joint filers ($50,000 to $75,000 for singles) | $375 billion | $50 billion |

| Phase out rebates from $80,000 to $130,000 for joint filers ($40,000 to $65,000 for singles) | $350 billion | $75 billion |

| Phase out rebates from $80,000 to $130,000 for joint filers ($40,000 to $65,000 for singles) and set child rebate to $500 in light of CTC expansion* | $300 billion | $125 billion |

| Phase out rebate based on 2020 income gains | Unknown | Substantial |

Source: CRFB calculations. *The House package would expand the Child Tax Credit from $2,000 to $3,000 ($3,600 for children under age 6) and make it fully refundable for one year.

#4: Extend and Taper Expanded Unemployment Benefits

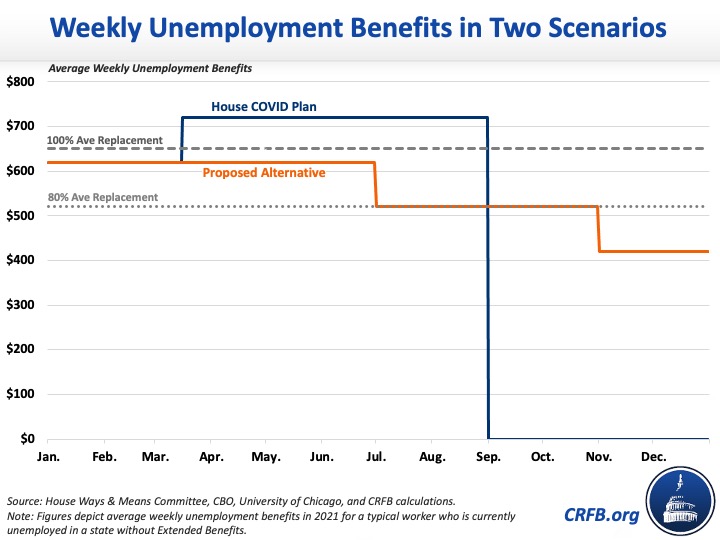

Currently, unemployed workers — including the self-employed and gig workers — can collect unemployment benefits through mid-March with a $300 per week federal supplement. The House bill would boost this supplement to $400 per week, but benefits would expire at the end of August. This makes little sense, as a $400 per week supplement would mean two-thirds of beneficiaries would collect more in benefits than they would collect in paychecks (most income support programs are capped at 80 percent of wages) and it is widely expected that high levels of joblessness will continue beyond August. Rather than boost-and-cliff unemployment benefits, policymakers should consider extending the current $300 supplement and then gradually taper it down as the pandemic ends and the economy recovers. This would ideally be done with automatic triggers but could also be based on current economic projections. A reasonable package could continue benefits through the end of 2021, at a net cost of $50 to $75 billion.

#5: Establish Triggers so Aid Matches Needs of the Economy

Rather than design a package based on what policymakers think the economy will look like, they should consider incorporating triggers that allow the package to adjust automatically based on what actually happens in the economy. For example, the unemployment supplement could be phased down based on employment levels in each state and expanded unemployment benefits eligibility could expire once national employment has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, state and local aid could be distributed quarterly based on economic conditions in each state. Ideally, triggers would be two-sided (see our Medicaid proposal), provide needed support in bad times, and reduce borrowing in good times. Regardless, triggers would help right-size the package to actual needs and conditions.

Budgetary Impact of Modifications

The adjustments suggested above, setting aside the triggers, could reduce the cost of the package from $1.9 trillion to $1.3 trillion with extended support for unemployed workers through the end of the year as opposed to the end August. This would still be over three times the size of the projected output gap for 2021 and therefore still large enough to support a full economic recovery. Additional revisions could reduce the size of the package even more. For example, the package boosts funding to the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) Disaster Relief Fund well above its pre-pandemic level and likely provides excessive funding to colleges and universities. It also supports restaurants and small businesses with additional rounds of grants, whereas preferential loans could be far more cost-effective. In a future post, we will put forward additional cost-reducing proposals. Taken together, these adjustments could reduce the size of the package to $1.1 trillion.

| Policy | Cost/Savings (-) |

|---|---|

| House Package Under Consideration | $1.9 trillion |

| Remove or Offset Unrelated Policies' | -$312 billion |

| Right-Size State and Local Aid to Match Need^ | -$310 billion |

| Better Target Rebates Based on Need | -$125 to -$50 billion |

| Extend and Taper Unemployment Benefits | $50 to $75 billion |

| Subtotal Cost of Revised Package | ~$1.3 trillion |

| Additional Cost Reductions* | -$200 billion |

| Total Cost of Revised Package | ~$1.1 trillion |

Source: CRFB calculations. 'Includes expanded Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Care Tax Credit, Affordable Care Act subsidies and Medicaid expansions, an increase in the federal minimum wage to $15/hour by 2025, and a few smaller policies. ^Reduces direct aid to state and local governments from $350 billion to $100 billion and aid to public K-12 schools from $100 billion to $70 billion. *Includes reductions of funding to FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund and colleges and universities, additional targeting for rebates (such as consolidating with CTC expansions), and other adjustments.

The COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis are far from over, and more relief and support is needed to get us through it. However, the $1.9 trillion relief package currently under consideration in the House would spend too much and would poorly target most of its spending relative to actual needs.

While our suggested improvements are only illustrative, they show a clear path to improving the package.

Note: This blog was updated on 2/25 to add more context on the size of tax credit available to families.