ARCHIVE: Appropriations 101

- What are appropriations?

- How does Congress determine the total level of appropriations?

- How will this year's appropriations process be different?

- How does Congress allocate appropriations?

- How are appropriations levels enforced?

- What happens if funds are needed outside the appropriations process?

- What role does the President play in the appropriations process?

- What is the timeline for appropriations?

- What happens if appropriations bills do not pass by October 1?

- What is a continuing resolution?

- What happens during a government shutdown?

- Do agencies have any discretion in how they use funds from appropriators?

- What is the difference between appropriations and authorizations?

- Where are the House and Senate in the current appropriations process?

What are appropriations?

Appropriations are annual decisions made by Congress about how the federal government spends some of its money. In general, the appropriations process addresses the discretionary portion of the budget – spending ranging from national defense to food safety to education to federal employee salaries – but excludes mandatory spending, such as Medicare and Social Security, which is spent automatically according to formulas.

How does Congress determine the total level of appropriations?

After the President submits the Administration’s budget proposal to Congress, the House and Senate Budget Committees are each directed to report a budget resolution that, if passed by their respective houses, would then be reconciled in a budget conference (see Q&A: Everything You Need to Know About a Budget Conference).

The resulting budget resolution, which is a concurrent resolution and therefore not signed by the President, includes what is known as a 302(a) allocation that sets a total amount of money for the Appropriations Committees to spend. For example, the conferenced budget between the House and Senate set the 302(a) limit for Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 at $1.017 trillion.

In the absence of a budget resolution, each chamber may enact a deeming resolution that sets the 302(a) allocation for that chamber. Until recently, deeming resolutions have been unnecessary because both the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA18) and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA19) gave the Chairs of the Budget Committees authority to set the 302(a) allocation for the Appropriations Committees in lieu of the respective chambers passing formal resolutions. For the last four consecutive years, the statutory discretionary spending cap levels were set at the amounts provided by those budget deals.

Discretionary spending has been subject to statutory spending caps since FY 2012 (and additional cuts through sequestration beginning in 2013), though this current fiscal year will be the last year those caps will be in effect. The Budget Control Act of 2011 set discretionary caps through the end of FY 2021, which have been modified by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019.

How will this year’s appropriations process be different?

Unless lawmakers enact new spending caps, discretionary spending levels for FY 2022 and future years will no longer be specified due to the expiration of the Budget Control Act of 2011. In the absence of a concurrent budget resolution, leaders of the House and Senate Budget Committees may propose deeming resolutions at whatever level they find necessary to fund discretionary priorities for the fiscal year, but each chamber must pass its own deeming resolution to officially set 302(a) allocations. In the House, this can be done by a simple majority vote, such as the FY 2022 deeming resolution passed on June 14. However, in the Senate there would be no privileged consideration of such a resolution, making it vulnerable to the filibuster.

The discretionary spending level lawmakers choose for FY 2022 could shape the trajectory of spending for the next decade. Discretionary funding is expected to grow each year, but the extent of that growth could be limited by a new agreement on spending caps. Agreement on future discretionary spending could also improve the budget process, leading to more timely enactment of appropriations.

How does Congress allocate appropriations?

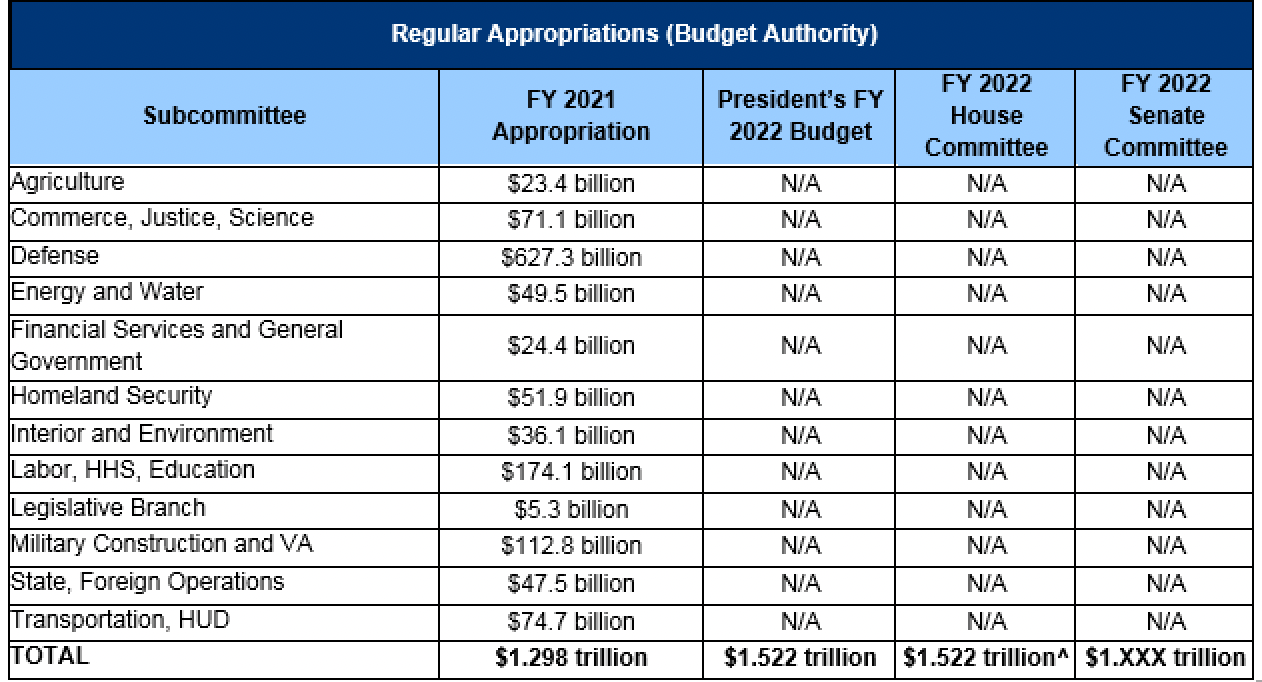

Once they receive 302(a) allocations, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees set 302(b) allocations to divide total appropriations among the 12 subcommittees dealing with different parts of the budget. The subcommittees then decide how to distribute funds within their 302(b) allocations. The 302(b) allocations are voted on by the respective Appropriations Committees, but they are not subject to review or vote by the full House or Senate. The table below lists the FY 2021 regular (non-war, non-disaster) appropriations along with the House and Senate FY 2022 302(b) allocations. The table will be updated as both the House and Senate Appropriations Committees release their 302(b) allocations.

Source: House Appropriations Committee, Senate Appropriations Committee, CBO estimate of H.R. 133, Office of Management and Budget.

*In addition to base discretionary appropriations provided in the table, final FY 2021 spending measures also included a total of $77 billion in Overseas Contingency Operations spending, $68.65 billion of which is designated for the Department of Defense, $8 billion of which is designated for the Department of State, and $350 million of which is designated for military construction. Including OCO funds, disaster relief, emergency requirements, and program integrity, FY 2021 spending measures provided $1.616 trillion in budget authority.

^According to the House Budget Committee, the deeming resolution incorporates certain technical and scorekeeping adjustments to translate the topline appropriations number from the President's budget request into a formal 302(a) allocation. The House deeming resolution provides for $1.506 trillion in regular appropriations for FY 2022, but all 12 appropriations bills are expected to total the administration request of $1.522 trillion as they are released.

Each subcommittee proposes a bill that ultimately must pass both chambers of Congress and be signed by the President in order to take effect. Although the budget process calls for 12 individual bills, all of them are often combined into what is known as an omnibus appropriations bill, and sometimes a few are combined into what has been termed a minibus appropriations bill.

How are appropriations levels enforced?

If any appropriations bill or amendment in either chamber exceeds the 302(b) allocation for that bill, causes total spending to exceed the 302(a) allocation, or causes total discretionary spending to exceed any statutory spending cap in place (if applicable), any Member of Congress can raise a budget “point of order” against consideration of the bill. The House can waive the point of order by a simple majority as part of the bill’s rule for floor consideration, and the Senate can override it through a 60-vote majority. Statutory spending caps come with even stricter rules and can result in consequences aimed at correcting violations, such as across-the-board cuts to put spending in line with the overall caps or other mechanisms to ensure fiscal responsibility.

What happens if funds are needed outside of the appropriations process?

After initial appropriations bills have been signed into law, Congress can pass a supplemental appropriations bill in situations that require additional funding immediately, rather than waiting until the following year’s appropriations process. Supplementals are often used for emergencies such as natural disasters or military actions. Occasionally, Congress has used supplemental appropriations to stimulate the economy or to provide more money for routine government functions after determining that the amount originally appropriated was insufficient. Supplemental appropriations bills are subject to the same internal and statutory spending limits as regular appropriations and require the same offsets to ensure they do not exceed spending limits unless designated as emergency spending.

What role does the President play in the appropriations process?

Although Presidents have no power to set appropriations, they influence both the size and composition of appropriations by sending requests to Congress. Specifically, each year the President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) submits a detailed budget proposal to Congress based on requests from agencies. The appendix to the President’s budget submission contains much of the technical information and legislative language used by the Appropriations Committees. In addition, presidents must sign or veto each of the appropriations bills, giving them additional influence over what the bills look like.

What is the timeline for appropriations?

The 1974 Budget Act calls for the administration to submit their budget request by the first Monday in February and for Congress to agree to a concurrent budget resolution by April 15. The House may begin consideration of appropriations bills on May 15 even if a budget resolution has not been adopted, and it is supposed to complete action on appropriations bills by June 30 (the process is generally designed for the House to take the lead on appropriations and the Senate to follow). However, none of these deadlines are enforceable, and they are regularly missed. The practical deadline for passage of appropriations is October 1, when the next fiscal year begins and the previous appropriation bills expire. For a full timeline of the budget process, read more here.

What happens if appropriations bills do not pass by October 1?

If appropriations bills are not enacted before the fiscal year begins on October 1, federal funding will lapse, resulting in a government shutdown. To avoid a shutdown, Congress may pass a continuing resolution (CR), which extends funding and provides additional time for completion of the appropriations process. If Congress has passed some, but not all, of the 12 appropriations bills, a partial government shutdown can occur.

What is a continuing resolution?

A continuing resolution, often referred to as a CR, is a temporary bill that continues funding for all programs based on a fixed formula, usually at or based on the prior year’s funding levels. Congress can pass a CR for all or just some of the appropriations bills. CRs can increase or decrease funding and can include “anomalies,” which adjust spending in certain accounts to avoid technical or administrative problems caused by continuing funding at current levels, or for other reasons.

What happens during a government shutdown?

A shutdown represents a lapse in available funding, and during a shutdown the government stops most non-essential activities related to the discretionary budget. To learn more, see Q&A: Everything You Should Know About Government Shutdowns.

Do agencies have any discretion in how they use funds from appropriators?

Executive branch agencies must spend funds provided by Congress in the manner directed by Congress in the text of the appropriations bills. Appropriations bills often contain accompanying report language with additional directions, which are not legally binding but are generally followed by agencies. In some instances, Congress will provide for very narrow authority or use funding limitation clauses to tell agencies what they cannot spend the money on. That said, Congress often provides broad authority, which gives agencies more control in allocating spending. Agencies also have some authority to reprogram funds between accounts after notifying (and in some cases getting approval from) the Appropriations Committees.

What is the difference between appropriations and authorizations?

Authorization bills create, extend, or make changes to statutes and specific programs and specify the amount of money that appropriators may spend on a specific program (some authorizations are open-ended). Appropriations bills then provide the discretionary funding available to agencies and programs that have already been authorized. For example, an authorization measure may create a food inspection program and set a funding limit for the next five years; however, that program is not funded by Congress until an appropriations measure is signed into law. The authorization bill designs the rules and sets out the details for the program, while the appropriations bill provides the actual resources to execute the program. In the case of mandatory spending, an authorization bill both authorizes and appropriates funding for a specific program without requiring a subsequent appropriations law.

Where are the House and Senate in the current appropriations process?

Congress began appropriations work for FY 2022 in March, and the House began marking up individual appropriations bills in June. Discretionary spending levels are no longer subject to caps under the Budget Control Act of 2011 (see Understanding the Sequester), as they had been since FY 2012, and additional sequestration, as they had been since FY 2013. This means that lawmakers have more leeway to set discretionary spending however high they would like, as long as the appropriations bills written in accordance with these spending levels can ultimately pass both the House and the Senate.

Although Congress is supposed to complete a budget resolution to lay out fiscal principles and set an appropriations level, lawmakers have not adopted one. Lawmakers are using a procedure known as "deeming," allowing the Appropriations Committees to begin their work assuming adherence to an overall discretionary spending level known as a 302(a). They could also adopt a more slimmed-down version of a budget resolution later that includes a 302(a) allocation and triggers the use of reconciliation for future policy priorities.

Once a 302(a) allocation is adopted through a budget resolution or through deeming, spending totals for each of the 12 appropriations bills, or 302(b) allocations, then need to be formally adopted by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. As in previous years, the House is expected to take the lead on marking up and passing appropriations bills over the summer. Last year, the Senate did not even release most of its FY 2021 appropriations bills until the fall, after the new fiscal year had already started.

For a detailed explanation of how the chambers can move forward with appropriations without passing a budget resolution, see our blog House and Senate Move Forward on Appropriations. To follow the progress of appropriations throughout the process, see our Appropriations Watch: FY 2022.