Analysis of CBO's July 2021 Budget and Economic Outlook

Today, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released initial details of its updated Budget and Economic Outlook, accounting for enactment of the American Rescue Plan and months of new economic data. CBO’s new baseline shows:

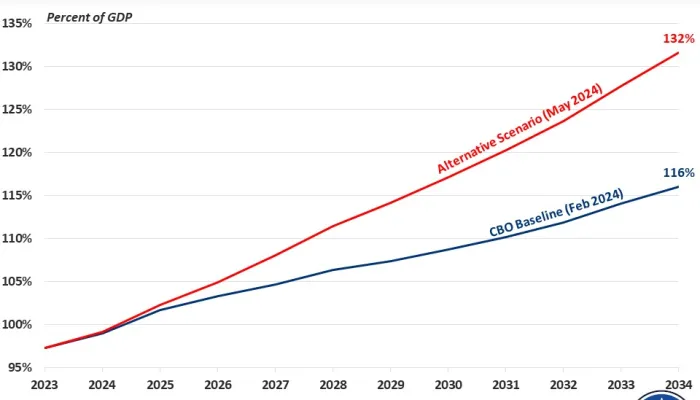

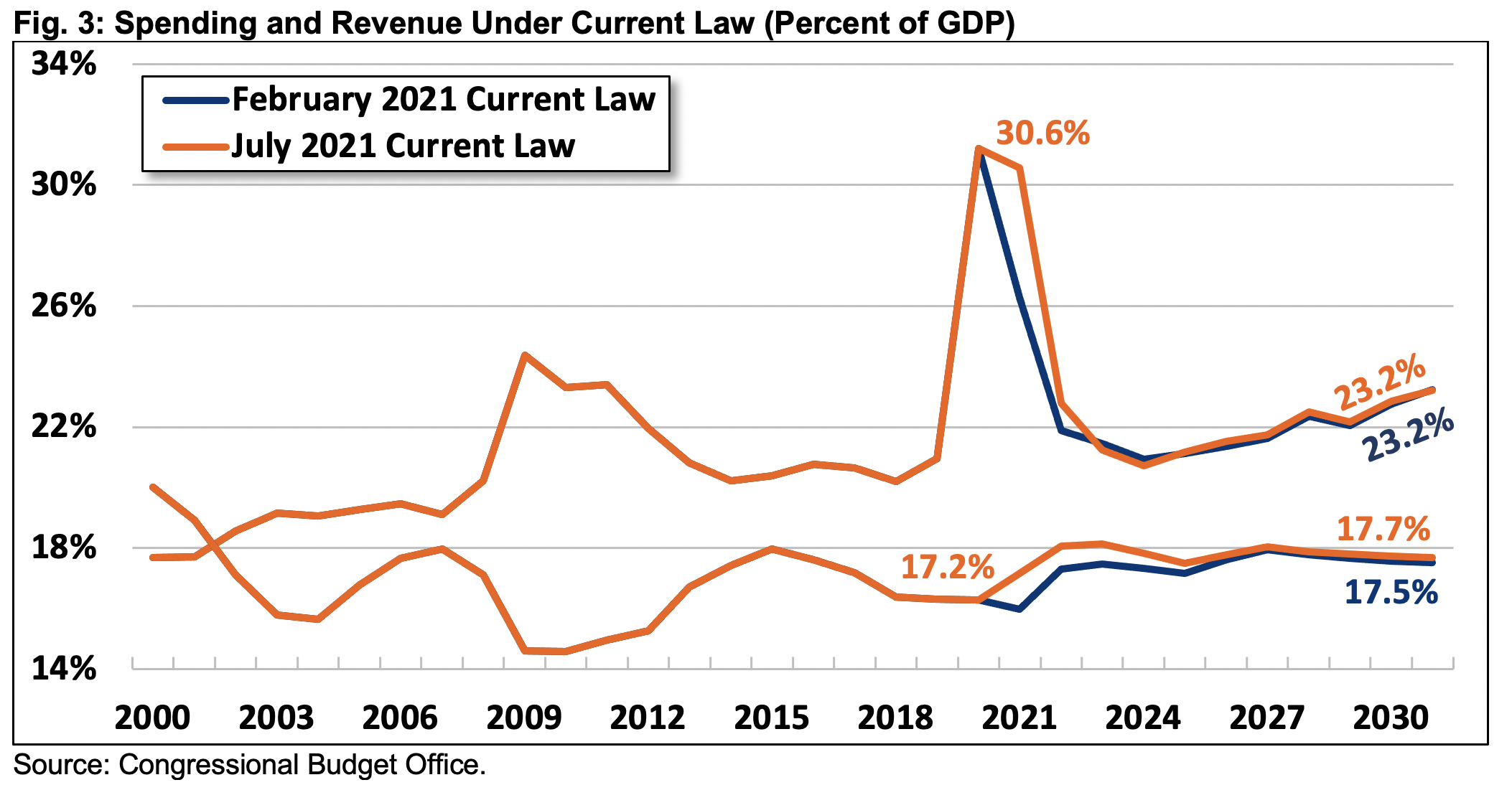

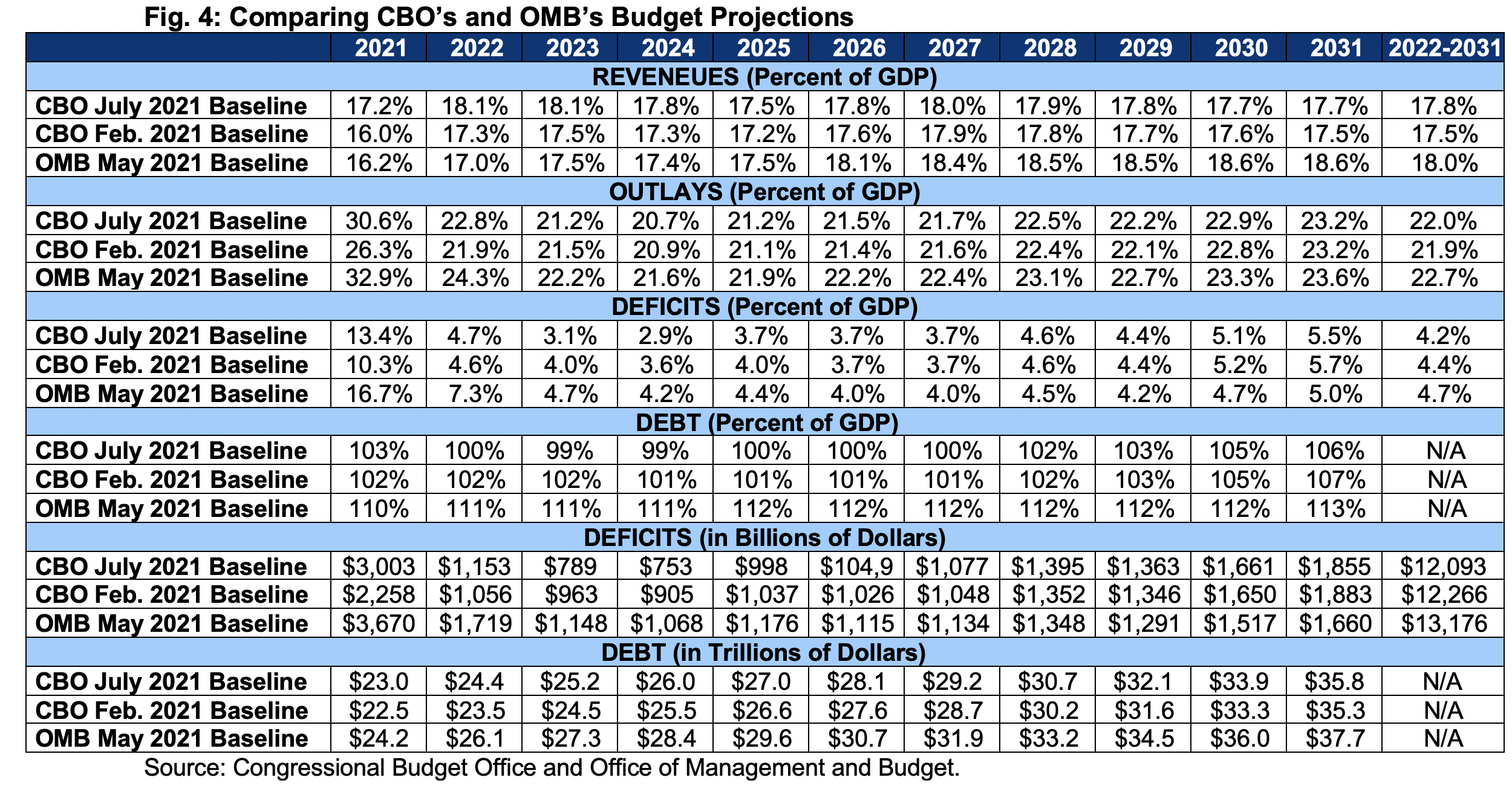

- Federal debt held by the public will rise from 100 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 to 103 percent in 2021 and reach a record 106 percent by 2031. In nominal dollars, debt will increase by $13.5 trillion, from $22.3 trillion today to $35.8 trillion by the end of 2031.

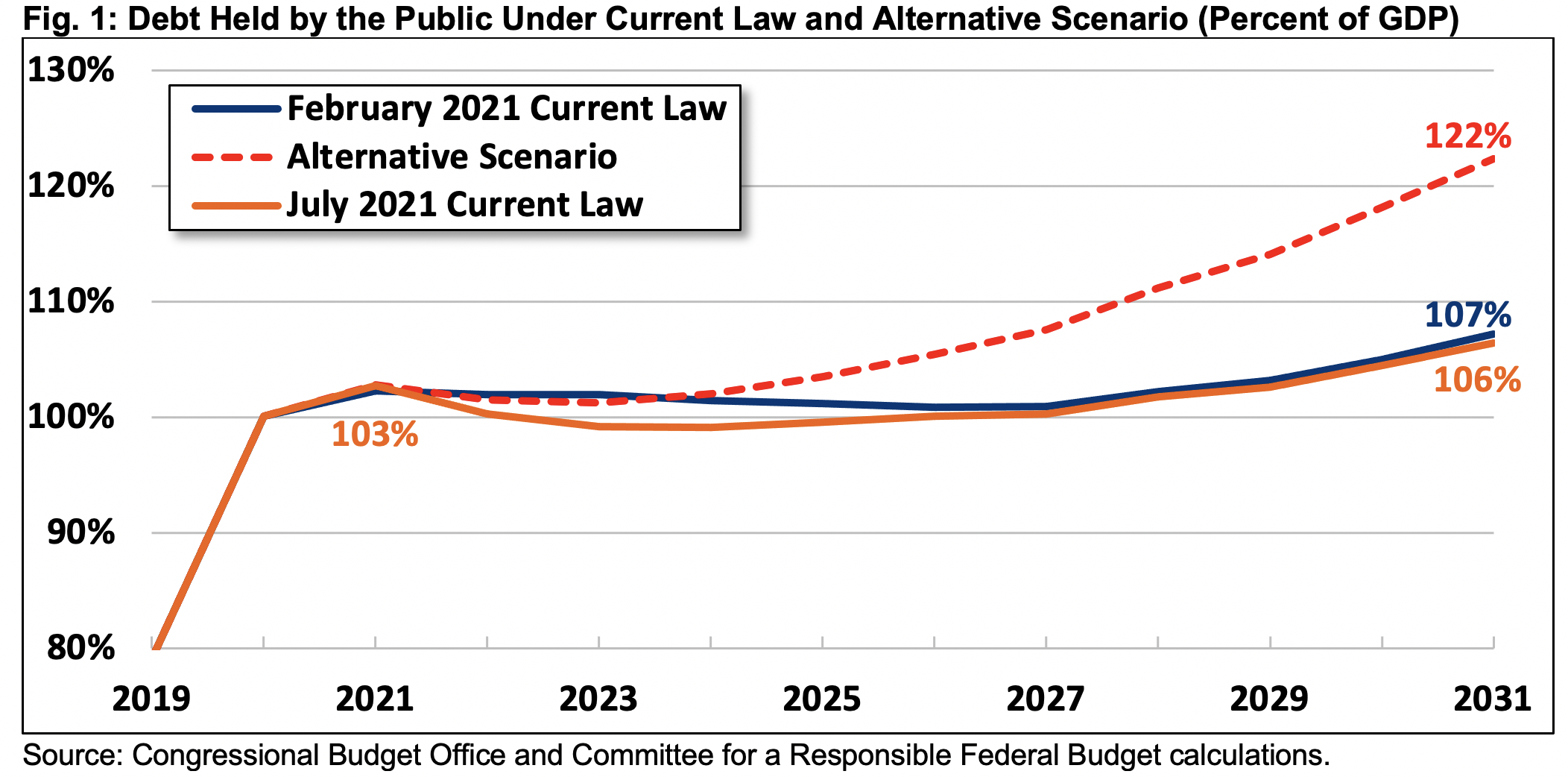

- The budget deficit will total $3.0 trillion (13.4 percent of GDP) in FY 2021, average $1.2 trillion (4.2 percent of GDP) over the next decade, and reach $1.9 trillion (5.5 percent of GDP) by 2031.

- Deficits will total $15.1 trillion between FY 2021 and 2031, $0.6 trillion higher than previously projected. The American Rescue Plan increased deficits by roughly $2.0 trillion, meaning economic and technical changes – such as a stronger economy – reduced projected deficits by about $1.4 trillion.

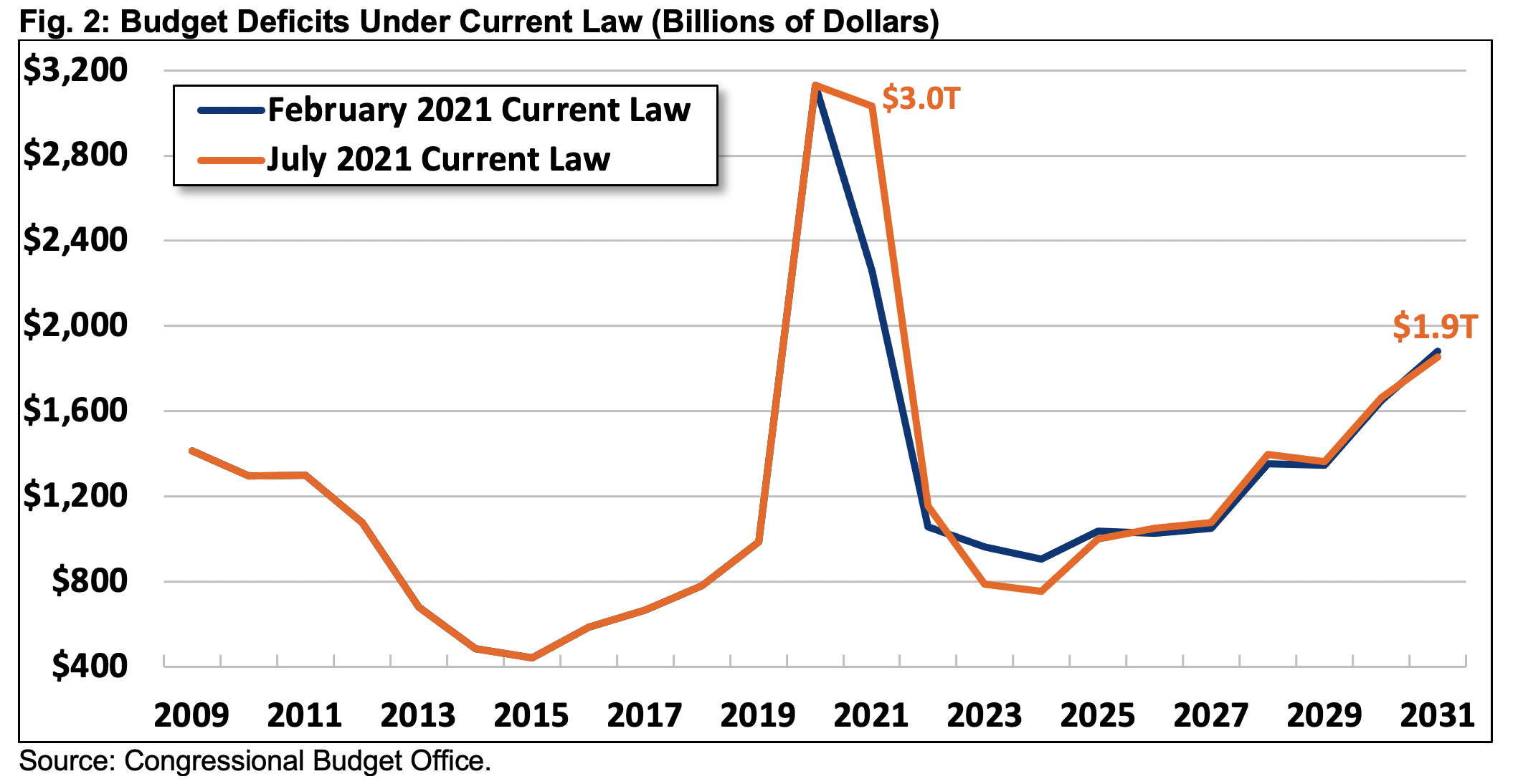

- Rising deficits and debt are driven by a disconnect between spending and revenue. CBO estimates spending will average 22.0 percent of GDP over the next decade, compared to a historical average of 20.6 percent of GDP. Revenue will average 17.8 percent of GDP, compared to a historical average of 17.3 percent of GDP.

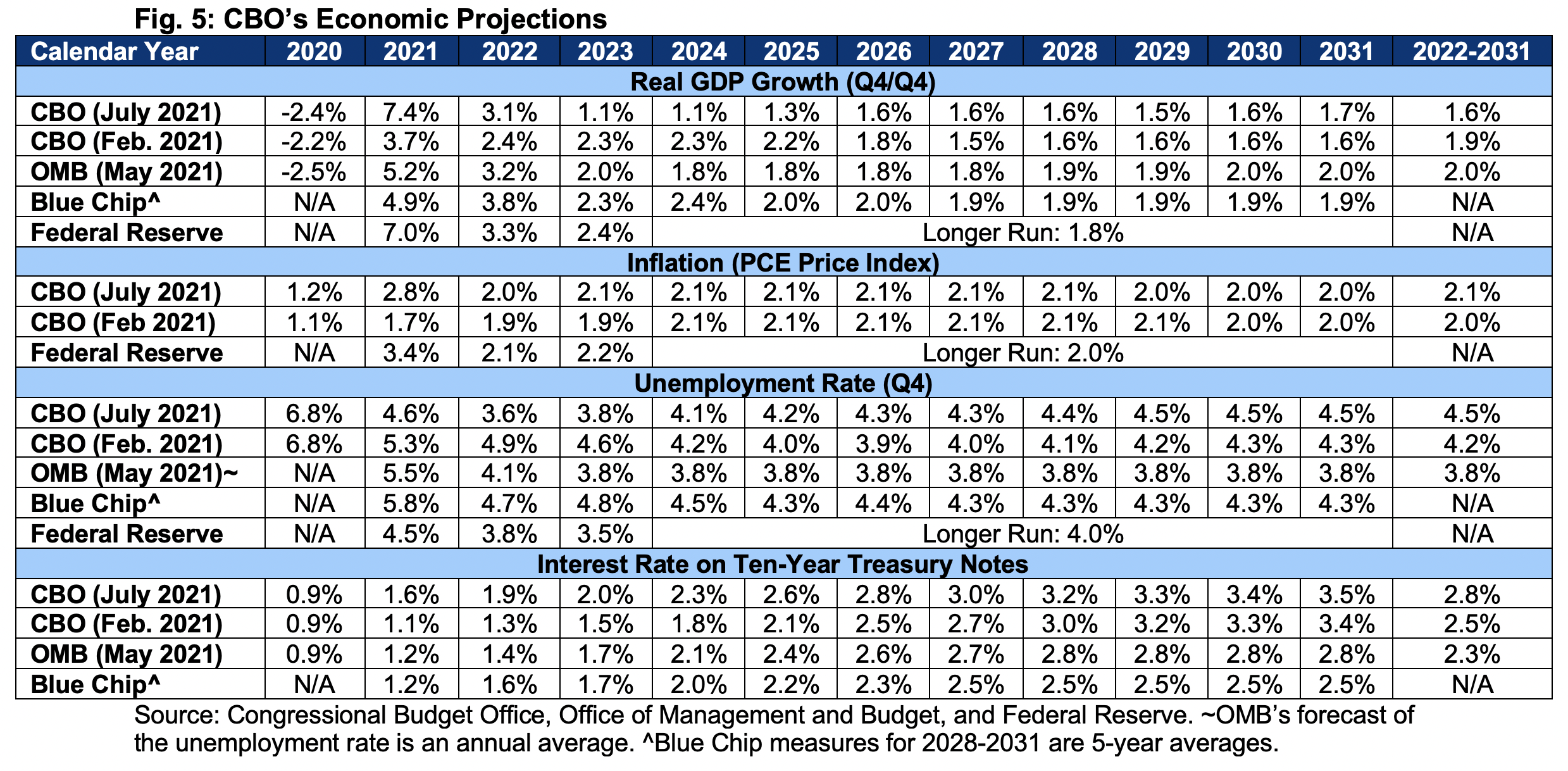

- As the economy recovers from the COVID-induced recession and absorbs enacted fiscal stimulus, CBO projects strong near-term economic growth and relatively high near-term inflation. CBO projects the economy will grow by 7.4 percent in calendar year 2021 and 3.1 percent in 2022, which is above its pre-pandemic trend. Inflation will total 2.8 percent in 2021 and 2.0 percent in 2022.

- Beyond 2022, CBO projects the economy will grow by an average of 1.5 percent per year (1.7 percent in 2031) and inflation will average 2.1 percent per year. CBO projects unemployment will fall to a low of 3.7 percent in 2023 and rise to 4.5 percent by 2031.

With debt already approaching record levels, it is important that policymakers resist calls to increase it further. Extending existing policies or enacting new ones, without sufficient offsets, could further worsen an already daunting fiscal picture.

Instead, policymakers should begin to address long-term debt growth by debating and enacting gradual tax and spending reforms.

The United States Faces Record Debt Levels

CBO estimates debt will reach record levels. Under current law, federal debt held by the public will rise from 100 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2020 to 103 percent by the end of 2021. From there, it will dip slightly to a low of 99 percent of GDP by FY 2024 before rising continuously to more than 106 percent by the end of FY 2031 – surpassing the prior record set just after World War II in 1946.

In nominal dollars, debt will grow from $21.0 trillion at the end of FY 2020 to $23.0 trillion in 2021 and to $35.8 trillion by the end of FY 2031. This $12.8 trillion increase between FY 2021 and 2031 is similar to what was projected in February. However, the debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to be slightly lower in FY 2031 – 106.4 percent instead of 107.2 percent – due to a higher estimate of nominal GDP.

The modest reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the next few years appears to be driven by projections of rapid economic growth combined with low net interest payments as a result of the low interest rates available over the past year and a half. As the economy normalizes, debt is projected to resume its upward trajectory.

Debt levels could be significantly higher if policymakers extend most expiring tax cuts and grow annual appropriations with the economy instead of inflation. Under our alternative scenario, debt would fall slightly less than the current law projection and would fall to a low of 101 percent of GDP in 2023. From there, debt would rise much more sharply to a record 108 percent of GDP by FY 2027 and to 122 percent by 2031.

The United States Faces Large Deficits as Spending and Revenue Diverge

High and rising debt is driven by persistent annual budget deficits. CBO estimates the budget deficit will total $3.0 trillion this year, fall to $1.2 trillion in FY 2022 and to $753 billion in 2024 as COVID relief winds down and the economy recovers, and then rise gradually to $1.9 trillion by 2031. As a share of the economy, the deficit will fall from 13.4 percent of GDP in FY 2021 to a low of 2.9 percent in 2024 before growing to 5.5 percent by 2031.

This year’s nominal dollar deficit will the second largest in history and the sixth largest as a share of GDP – eclipsed only by five years of borrowing to fight World War II and COVID-19.

CBO estimates deficits will total $15.1 trillion (4.9 percent of GDP) over the 11-year period from 2021 to 2031, which is $0.6 trillion (0.1 percent of GDP) higher than CBO’s February projection of $14.5 trillion (4.8 percent of GDP). Given the $2.0 trillion cost (including interest) of the American Rescue Plan, this suggests that economic and technical changes (including feedback from the American Rescue Plan) reduced projected budget deficits by roughly $1.4 trillion.

Looking forward, over the 2022-2031 budget window CBO projects spending will total $63.4 trillion (22.0 percent of GDP) and revenue will total $51.3 trillion (17.8 percent of GDP).

This disconnect comes mostly after the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent relief efforts, which increased spending from 21.0 percent of GDP ($4.4 trillion) in FY 2019 to 31.2 percent of GDP ($6.6 trillion) in 2020 and a projected 30.6 percent of GDP ($6.8 trillion) in 2021.

CBO projects that spending as a share of GDP will drop to a low of 20.7 percent of GDP ($5.4 trillion) in FY 2024 before rising to 23.2 percent of GDP ($7.8 trillion) by 2031. Revenue, meanwhile, will reach a high of 18.1 percent of GDP ($4.6 trillion) in FY 2023 before falling back to 17.7 percent of GDP ($6.0 trillion) by 2031, assuming expiration of many Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provisions.

CBO Projects Strong Near-Term Growth and Higher Inflation

As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to absorb fiscal and monetary support, CBO projects strong near-term economic growth, a relatively rapid jobs recovery, and higher-than-normal rates of inflation.

After contracting by 2.4 percent by the end of calendar year (CY) 2020, CBO forecasts the economy – as measured by real GDP – to grow by 7.4 percent by the end of 2021 and 3.1 percent by the end of 2022, exceeding its long-term potential. The unemployment rate will fall from a high of 6.8 percent at the end of CY 2020 to 4.6 percent by the end of 2021 and 3.6 percent by the end of 2022.

Beyond 2022, CBO expects growth to slow to 1.1 percent per year for two years and then stabilize at about 1.6 percent per year thereafter. The unemployment rate will reach 4.5 percent by 2031.

On inflation, CBO expects the Consumer Price Index (CPI) will increase by 3.4 percent in 2021 and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index to grow by 2.8 percent. Beyond that, CBO expects PCE inflation of roughly 2.1 percent per year and CPI of 2.4 percent per year.

CBO expects interest rates will rise over the next decade, with the ten-year bond rate growing from 0.9 percent in 2020 and 1.6 percent in 2021 to 3.5 percent by 2031.

CBO’s forecast is similar to that of other estimators, though its near-term growth and inflation estimates are somewhat higher than those based on earlier economic data.

Conclusion

CBO’s latest budget projections confirm that the country is on an unsustainable fiscal trajectory. While deficits and debt will temporarily subside as the economic recovery takes hold, debt will soon begin to grow and will reach a new record of 106.4 percent of GDP by the end of the decade.

Unfortunately, much of the current political discussion revolves around policies that would further worsen the fiscal outlook by boosting discretionary appropriations and enacting trillions of dollars in new spending initiatives. Any such legislation should be fully paid for so as to not add to the debt.

Similarly, policymakers should pay for the extension of any expiring provisions. Under our alternative scenario – which assumes expiring provisions continue and discretionary spending grows with the economy rather than inflation – debt will reach 122 percent of GDP by the end of the decade.

As the current crisis subsides and the economy recovers, policymakers will soon need to go beyond paying for new initiatives and work to get the country on solid fiscal ground. This includes actions to secure Social Security and other trust funds headed toward insolvency, limit the growth of the health care costs and other programs, and raise additional tax revenue. Adjustments can be phased in gradually but should be enacted sooner rather than later.