Would Reducing Fraud Make Social Security Solvent?

Ending benefit payments to thousands of beneficiaries would barely move the needle on solvency – there would need to be almost 10 million ineligible 106-year olds in order to save Social Security solely by ending fraudulent and mistaken payments. Moreover, even Mr. Trump’s own estimate of thousands of beneficiaries over age 106 who don’t exist is likely a significant overestimate.

According to a 2013 report by the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) Inspector General, there were just over 1,500 deceased individuals still receiving benefits in total, including many below the age of 106 and accounting for about $15 million in additional improper benefit payments. A 2015 report did find 6.5 million active Social Security numbers for people over the age of 112 – but only 13 of them were being used to receive benefits. A much bigger fraudulent use of the remaining numbers is to contribute payroll taxes into the system, not to collect benefits from it, a situation that applied to almost 67,000 of the numbers.

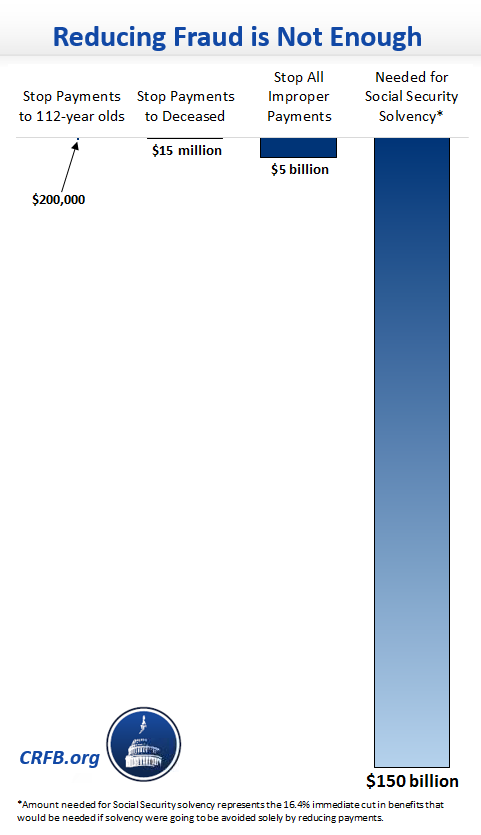

This data suggests the group Mr. Trump is referencing is between 13 and 1,500 recipients in size and is therefore costing the system between $200,000 and $15 million annually. To put that in context, total benefits this year will exceed $900 billion, meaning that stopping all of these payments would reduce program costs by between 0.00002 and 0.002 percent.

Even if SSA could somehow eliminate all improper payments, estimated by SSA at about $5 billion per year (which is likely impossible1), it would only reduce costs by at most 0.6 percent. This would extend the program’s solvency by about 4 months.

By comparison, the Social Security Trustees estimate restoring solvency by solely reducing benefits would require an immediate 16.4 percent cut – an equivalent of reducing Social Security benefits this year by about $150 billion.

Of course, waste is often in the eye of the beholder. Trump has previously suggested that rich people should voluntarily give up their Social Security benefits – if “waste” includes some people who are currently entitled to benefits, the savings could be larger; however, it would still be unlikely to ensure solvency. If Mr. Trump’s plan to save Social Security relies on cutting waste, fraud, and abuse, he would need to cut total benefits by 16.4 percent, not the fraction of one percent that he’s currently discussing.

The financing problems facing the Social Security Trust Funds are one reason why Congress and the President should reform Social Security so it can remain solvent for future generations. Try our Social Security Reformer to see various option for to raise revenue and slow the growth of benefits to see what this might look like.

There is a fairly small amount of waste, fraud, and abuse within the Social Security system. Although efforts should be taken to reduce it (and some are ongoing), even stopping all of the waste would not dramatically alter the course of Social Security’s finances.

Our Rating: False

1 “Improper payments” is a particular term that captures all payments to the wrong person, with insufficient documentation, or in the wrong amount (either too much or too little). In cases of improper documentation, such as deceased individuals, the entire amount is considered an improper payment. In cases of an over- or underpayment, just the amount paid over or under the scheduled benefit is tallied as improper. For several reasons, it would be difficult to recover the entire $3 billion figure we used here. Some of that amount is already recovered, and it costs money to recover additional overpayments. Some of the $3 billion is also an underpayment, so correcting the improper payment would spend more money.

Update: 3/18/16: We corrected the footnote to more accurately describe how improper payments are counted.

Update 4/25/16: We have updated this document to include newer data for the amount of improper payments ($5 billion in FY 2014), posted after this piece was originally published. The original version cited $3 billion in improper payments in FY 2013.