What Would the American Jobs Plan Mean for the Debt?

Recently, President Joe Biden unveiled his American Jobs Plan focused on upgrading and repairing America’s physical infrastructure, investing in manufacturing and research and development, and expanding long-term health care services. The plan includes $2.65 trillion of new spending and tax credits, focused mostly over the next eight years, and would be fully paid for within 15 years through corporate tax increases. Because it pairs temporary spending measures with permanent offsets, the plan would have near-term costs but eventually produce long-term budget savings. We estimate the plan would increase debt by 3 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2031 compared to current law, but reduce projected debt by 3 percent of GDP by 2041. The plan would reduce debt even further over the very long run.

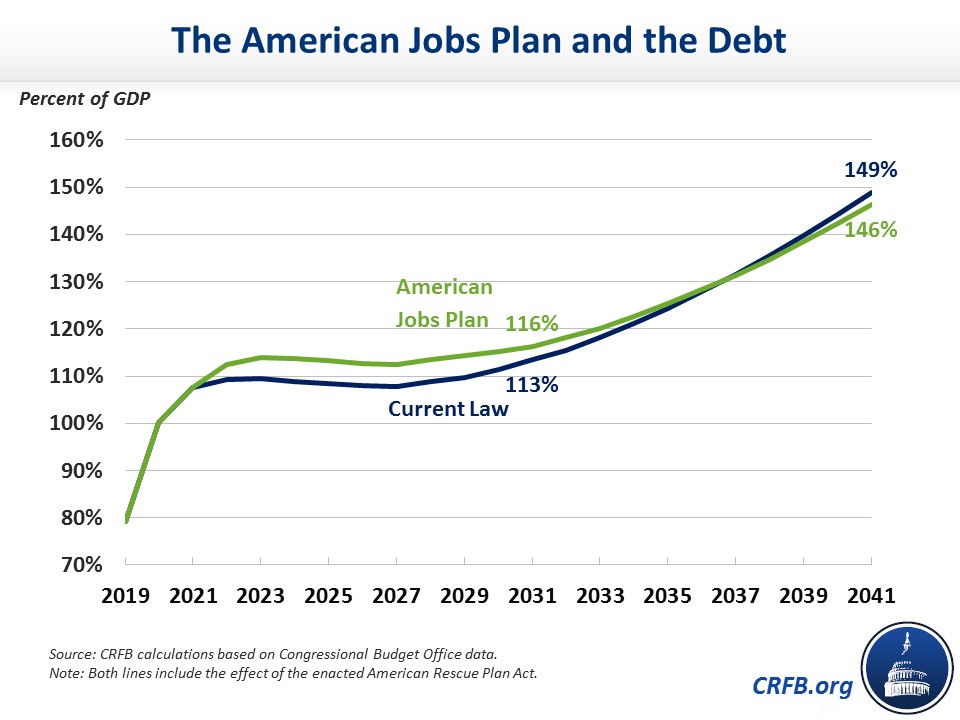

Following enactment of the American Rescue Plan Act last month, we projected that federal debt held by the public will reach 108 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) this fiscal year – higher than the prior record of 106 percent of GDP set just after World War II – and then rise to 113 percent of GDP by the end of 2031 and 149 percent by the end of 2041.

While the American Jobs Plan is deficit-neutral over a 15-year period, it would increase deficits over the traditional ten-year budget window – by $900 billion according to our estimates (closer to $1 trillion including interest). As a result, we estimate debt would grow to 116 percent of GDP by 2031, rather than 113 percent under current law.

Beyond 2031, however, the plan would reduce deficits by roughly $200 billion per year. By 2036, it would reduce debt to below current law projections, and after two decades, we estimate debt would be about 3 percent lower than under current law – 146 percent of GDP instead of 149 percent. Beyond that, we expect even more significant debt reduction since the permanent offsets in the plan would continue to reduce deficits, putting debt roughly 10 points below current law in 2051.

Of course, our projection that the American Jobs Plan would result in long-term debt reduction assumes its costs are credibly temporary and its offsetting revenue increases will be sustained for at least the next 15 years. Since both of these assumptions are far from certain, policymakers would be wise to offset spending in the plan over a more traditional ten-year window. This would also improve the plan's long-term fiscal effect. For example, if policymakers reduced the size of the package so that it would be fully offset within ten years instead of 15, debt-to-GDP would be 6 percent lower than under current law after 20 years rather than 3 percent. Of course, policymakers could also consider additional or alternative offsets.

Regardless of the exact budget window, it is critical that Congress follows the President's lead and fully offsets any new spending initiatives.