Trust Funds and the Budget

Charles Blahous's paper on the Affordable Care Act has sparked a lot of buzz, leading to some discussion about "double-counting" the Medicare savings and how to view the federal budget with regards to trust funds. Thinking about how the trust funds fit into the budget can be a headache-inducing topic, but we'd like to simplify the views and see how it relates to Blahous's view on the HI trust fund. It is an important topic since it comes up frequently, especially with regards to Social Security, and it will continue to come up with regards to the various trust funds the federal government maintains.

The simplified version of the discussion breaks down to two views: the unified budget view and the trust fund view.

The unified budget view simply sees the budget as the whole of spending and revenue, ignoring trust funds and legal limits on the ability to pay benefits that come from them. Take, for example, Social Security. Under this approach, the program would not be considered separately from other federal spending or revenues -- it is simply a program of disability and retirement benefits that the federal government funds from all incoming revenues, including from the payroll tax. Trust funds are not important under this view. Comparing the two sides of the federal ledger (total spending and payroll tax revenue) shows that the program is either in surplus, deficit, or balance--currently, it is running deficits.

When a baseline is constructed with this view, it is implicitly assumed that any trust fund that will run out of money will have that hole filled by general revenues from the Treasury. This is the way most people/organizations construct a baseline, including CBO. Taking this view, the ACA reduces Medicare spending by the full amount of its cuts, leading to net deficit reduction as a result of the entire bill. With the regards to double counting, if one takes this view, then one would say that the savings count for reducing the deficit but don't really matter for the purposes of trust fund solvency.

The trust fund view states that balances in the trust funds matter for the purposes of program impact on the deficit and legal limitations on outlays. This is the view people take when they point to the Social Security trust fund balances as proof that the program does not add to the deficit, and it is also to some extent the view that Blahous used in his paper by focusing on the consequences of trust fund insolvency. Constructing a baseline with this view would require that all programs be financed by their trust funds without any general revenue, whether that means automatically cutting spending to bring it in line with revenue or assuming that the dedicated financing is increased. This view would hold that the Medicare savings could strengthen HI trust fund solvency, but if it did so, it would not have any impact on the deficit.

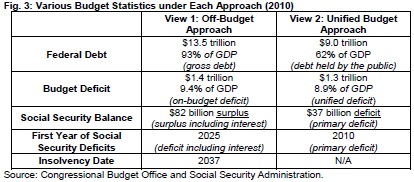

In a paper we wrote last year on Social Security and the budget, we compared these two views as it pertains to Social Security (note that we refer to the trust fund view as the off-budget view in this chart):

Neither view of the budget is necessarily wrong, but they do have different implications. Most baselines and projections tend to rely on the unified view since it provides a more realistic picture of debt going forward. Similar to how current policy baselines show more realistic policy outcomes than current law, that view assumes that Congress would more likely use general revenue transfers than allow transportation, disability benefits, Medicare, and Social Security spending to be cut significantly in one year. The unified view assumes that lawmakers will make good on the promises they have implicitly made, and thus highlights the extent to which they need to enact reforms to make good on those promises.

But taking the trust fund view, as Blahous does in his piece and as those claiming that Social Security does not add to the deficit, is not technically wrong either -- it is just a different way of looking at things.

What is wrong is to try to hold both views simultaniously in order to make two necesarily competing claims. Medicare savings cannot be said to both strengthen the HI trust fund and be available to offset new spending. Arguments to the contrary must rely on taking a mix of the two views: that dedicated financing flowing into a trust fund must go to future benefits and can't reduce deficits, and that reducing spending on a trust-fund financed program can reduce the deficit.

Neither view is necessarily wrong, but one must be consistent in their view when talking about the Affordable Care Act, Medicare, Social Security or any issue that involves trust funds in the federal budget.