Social Security Costs Keep Increasing Over the Long Term

CBO's Long-Term Budget Outlook, released last month, included updated projections for Social Security and Medicare, including individuals' expected benefits and taxes paid. The Social Security trust fund projections are very similar to last year's: the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund is scheduled to be insolvent sometime in Fiscal Year 2017 (which starts in October 2016) and the larger Old Age and Survivor's Insurance Trust Fund is expected to run out of money in 2031. If the two programs are considered as one (if Congress reallocates funds from one to another as necessary), the combined fund will be exhausted in 2029, one year sooner than projected in last year's report.

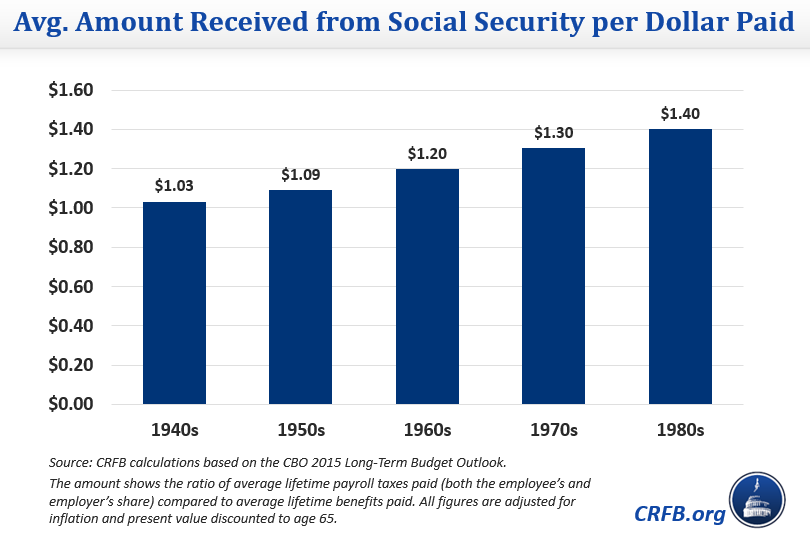

Some information that wasn't in last year's report (but was in a separate publication on Social Security) explains that each succeeding generation will get more out of Social Security than they paid in. Individuals born in the 1940s are expected to, on average, receive $1.03 for every dollar paid in Social Security taxes. This amount increases over time, with those born in the 1980s scheduled to receive $1.40 in benefits for every $1 paid in taxes, up from $1.03 for those born in the 1940s. These amounts assume that Social Security will continue to pay full benefits even after the trust fund runs out.

Future generations are getting more out of Social Security primarily because they are expected to live longer. Future retirees, who are expected to higher wages than current retirees, will have higher annual benefits and taxes, but longer life expectancy means that workers will spend a greater portion of their lifetime in retirement than past workers, so the return on lifetime taxes increases. Future generations are also expected to pay slightly less payroll tax on average, since CBO now assumes that income inequality will grow, and more wages will be earned above the maximum threshold for the Social Security tax (currently $118,500 a year).

The fact that Social Security benefits are scheduled to expand rapidly – due to population aging, longer lifespans, and growing benefit levels – while revenue falls slightly is why the program is scheduled for insolvency. As CBO explains, "if current laws remained unchanged, Social Security outlays would exceed the program’s revenues by almost 30 percent in 2025 and by more than 40 percent in 2040."

Restoring solvency would require additional revenue and/or reductions in future benefits. CBO estimates that it would take a payroll tax increase of 4.4 percentage points (1.4 percent of GDP), an about one-quarter benefit reduction, or some combination of the two to restore solvency. You can use our Social Security Reformer to look at the most commonly discussed options.

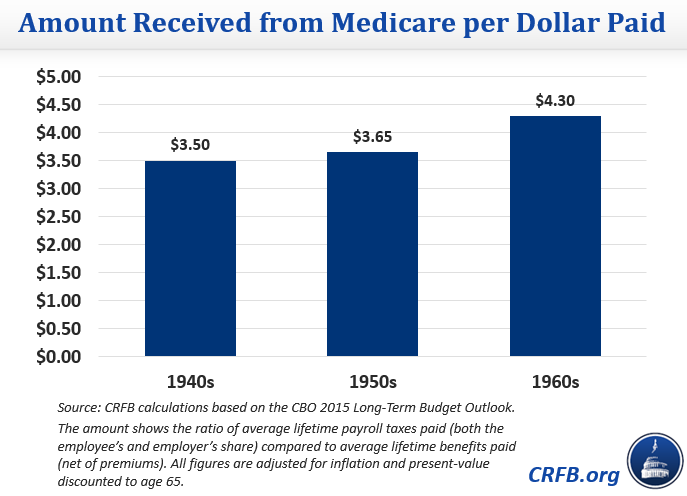

The imbalance between benefits received and taxes paid is even greater for Medicare, where beneficiaries receive $3 to $4 in benefits for every dollar they pay in taxes. This is in part because payroll taxes only pay for one part of Medicare, Part A, while Parts B and D are financed only in part by beneficiary premiums. Like the Social Security graph above, these numbers assume that Medicare continues to make full payments even after the Part A trust fund runs out within 15 years.

The impending insolvency of trust funds in Social Security and Medicare reflect the widening gap between benefits and taxes paid over time. Lawmakers will have to bring them in line to keep these programs on sound financial footing.

This blog is part of a series examining aspects of CBO's 2015 Long-Term Budget Outlook. Click here to read our 6-page summary of CBO's paper, or here for other blogs in the series.