Moving on Up: Interest Costs in the CBO Baseline

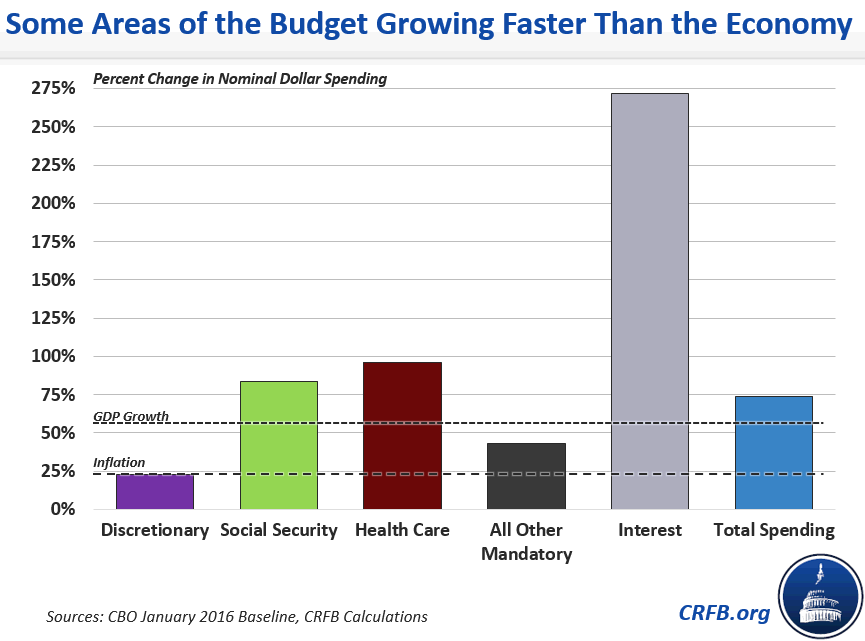

With the Congressional Budget Office releasing its final baseline last week, we know the dire fiscal future facing the country. Thanks to policymakers' disregard for fiscal discipline, the baseline is much worse than it had been in August. Of particular concern is the rapidly increasing interest costs in the baseline. Interest is the fastest growing type of spending over the next 10 years.

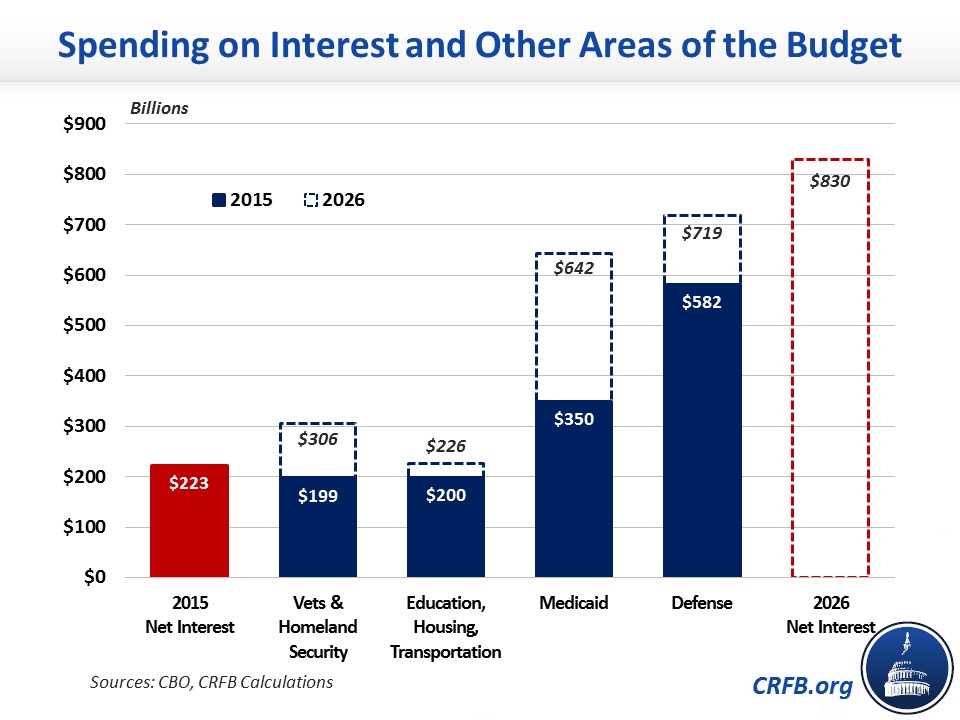

The $223 billion in interest costs during fiscal year (FY) 2015 resulted from servicing the $13.1 trillion debt at an average interest rate of 1.7 percent. Even at record-low interest rates, this is already more than we spend on the Departments of Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs combined. This is also more than current spending on the Departments of Education, Housing and Urban Development, and Transportation combined. Every dollar the United States devotes to interest payments is a dollar that either cannot fund national priorities or that must be collected through higher taxes. As interest rates rise back to more normal levels and debt continues to grow, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects spending on debt service to increase significantly.

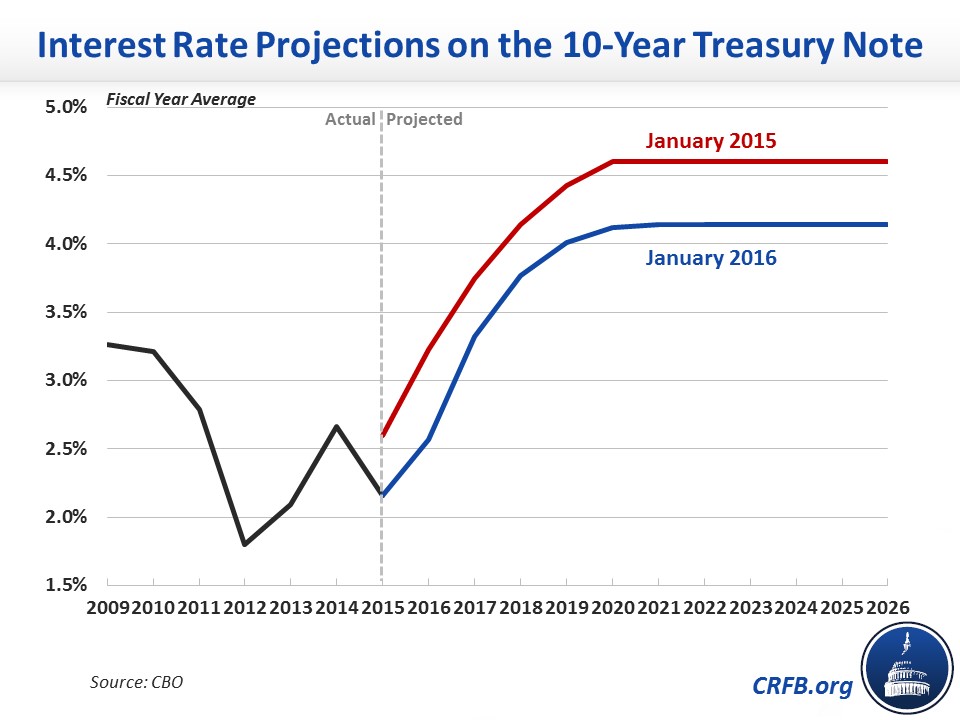

CBO projects the 10-year Treasury note interest rate to increase from 2.2 percent in 2015 to an average of 4.1 percent after 2019, and the interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills to increase from less than 0.05 percent in 2015 to 3.2 percent after 2019. CBO also projects debt held by the public will grow from $13.1 trillion at the end of fiscal year 2015 to $23.8 trillion by 2026.

As a result of these factors and deficit financing a year-end tax and spending deal, CBO's January baseline concluded that interest payments will rise (We have published charts and a paper explaining the January baseline).

In nominal dollars, net interest costs will nearly double between 2015 and 2019 from $223 billion to $438 billion; by 2026 interest costs will have more than tripled to $830 billion. As a share of the economy, federal interest payments are expected to double by 2022, from 1.3 to 2.6 percent of GDP, and then continue to grow to 3.0 percent of GDP by 2026. Interest payments will grow faster than every other major part of the budget, inflation, and the economy.

The annual budget deficit will rise from $439 billion in 2015, surpassing $1 trillion in 2022, and reaching $1.4 trillion in 2026. A notable amount of this is led by the $607 billion rise in interest payments. By 2022, interest payments will surpass how much the government spends on all of its investments, including research and development, education, training, and infrastructure. By 2026, interest payments will consume 16 percent of all revenue collected and represent slightly more than 1 out of every 8 dollars the government spends.

CBO also warns that if interest rates are higher than projected then the deficit would be notably worse. While the impact would be relatively small in 2016, amounting to only about $38 billion, the problem would compound over time increasing the deficit in 2026 by over a quarter of a trillion dollars. In all, if interest rates were 1 percentage point higher than baseline every year the debt would grow an additional $1.7 trillion by 2026.

Without a plan to reduce debt as a share of the economy from its current post-World-War-II historic highs, even small increases in interest rates beyond projected levels could significantly worsen an already unsustainable fiscal picture. The best way policymakers can protect against the risk of rising interest rates is to enact a thoughtful mixture of tax and spending reforms that put the debt as a share of the economy on a clear downward path over the long run.

See our paper for more detail of the January CBO Baseline: Analysis of CBO's January 2016 Budget and Economic Outlook.