More on Capital Gains and Tax Reform

Last week, we featured a piece by CRFB Senior Policy Director Marc Goldwein discussing one option to reduce tax rates while maintaining progressitivity and raising $1 trillion in revenue: eliminating the special rates for capital gains along with other deductions. In theory, a lower tax on capital gains might be preferred in order to incentivize savings. But there are also serious drawbacks to the approach, including the tax arbitrage that preferential rates encourage and the general fact that other rates must be higher to make up for the lost revenue.

We also discussed a joint House Ways and Means Committee/Senate Finance Committee hearing on capital gains, which unsurprisingly produced split opinions. Those in favor of a capital gains preference argued that it would encourage savings and thus help economic growth, and it would help compensate for double taxation of gains through the corporate income tax and illusory gains from inflation. Opponents argued that the preference was very regressive, increased complexity in the tax code, and did little to help economic growth.

Adding to the discussion on the tax treatment of capital gains are two helpful new papers from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). The JCT summarizes the current rules on taxation of capital gains and the end of the year changes under current law. Currently for taxpayers above the 15 percent bracket, the long-term capital gains (assets held for more than a year) tax rate is 15 percent while those in the lower brackets pay no capital gain tax. Under current law, the long-term capital gains tax will increase to 20 percent for the upper brackets and 10 percent for the lower brackets.

The capital gains tax, though, is not that straightforward. There are tax exclusions for assets passed on to heirs ("step-up" basis), portions of gains from home sales, and gains from certain small business stock. Deferral of tax burden exists for exchanges of similar property (like-kind exchanges) until the final property is sold, even if the exchanged properties have different values. Furthermore, some income that would normally be treated as earned income-- from sales of timber, livestock, and ore; coal royalties; and carried interest from partnerships to name a few -- gets capital gains treatment.

| Cost of Capital Gains Tax Preferences (billions) | ||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Capital Gains Preference* | $66.2 | $62.0 | $48.3 | $59.4 | $71.2 | $80.2 |

| Step-up Basis for Capital Gains at Death | $19.9 | $23.9 | $36.2 | $38.4 | $40.7 | $43.1 |

| Exclusion for Home Sales | $16.0 | $23.4 | $31.6 | $34.9 | $38.6 | $42.6 |

| Exclusion for Small Business Stock | $0.1 | $0.3 | $0.7 | $1.0 | $1.1 | $0.8 |

| Treatment of Certain Agricultural Income | $0.9 | $0.8 | $0.7 | $0.8 | $1.0 | $1.1 |

| Treatment of Timber Income | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 |

| Treatment of Coal Royalties | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 | $0.1 |

Source: OMB

*Includes carried interest. Excludes agriculture, timber, ore, and coal.

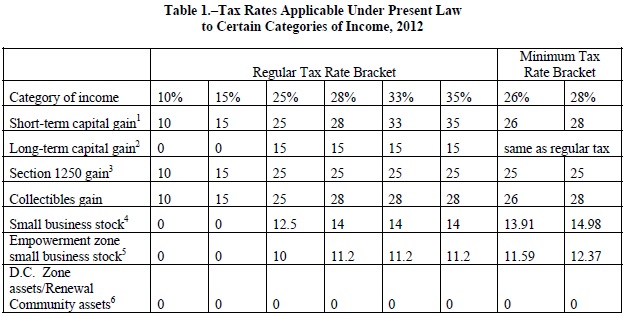

The JCT background report further reinforces a point brought up by Goldwein, that there is no one tax on capital gains, but rather a complex set of rules. This complexity in turn creates economic inefficiency and encourages efforts to classify or convert ordinary income into preferentially taxed capital gains. JCT itself demonstrated the complexity of capital gains rules for 2012 with a table in the report.

Chye-Ching Huang and Chuck Marr of CBPP argue that the special rates for capital gains and dividends should be reconsidered, claiming that the preference is economically inefficient, regressive, and expensive. Because the capital gains preference overwhelmingly benefits high-income earners, they say, it would be especially hard to both lower rates and raise more revenue while maintaining the code's progressitivity without raising that rate.

Having a lower tax rate for capital gains might be a policy that lawmakers choose to have. But the revenue will likely have to be made up with higher rates, which is why plans like Simpson-Bowles and Domenici-Rivlin chose to eliminate the preference. Lawmakers should put all preferences on the table, including those for capital gains and dividends, so as not to limit themselves as they work to improve the tax code and put the debt on a downward path.