Employee Retention Credit Faces 7X Cost Overrun

The pandemic-era Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERC) was designed to help businesses retain workers during the pandemic. But after low initial uptake during the pandemic itself, employers have been applying for the credit in droves – some fraudulently so– thanks to a cottage industry of “ERC promoters” who are encouraging applications after the fact.

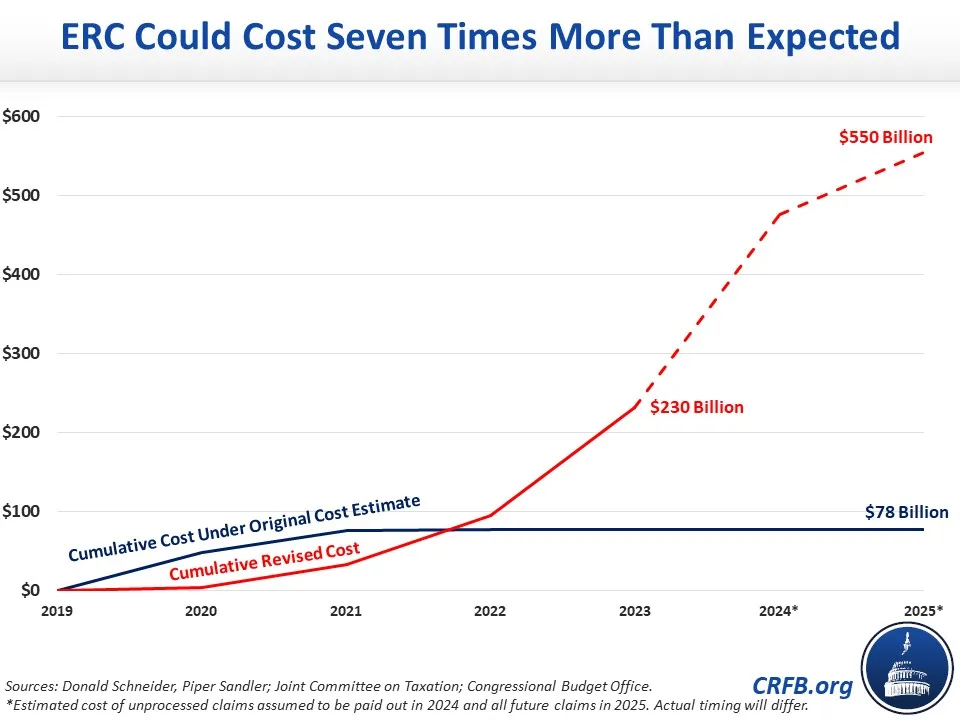

While original scores put the cost of the ERC at about $78 billion, it may end up costing over $550 billion – seven times the initial deficit impact – and mostly go to businesses who do not need it to retain workers or survive the pandemic. Policymakers should act quickly to cut off ERC payments and recover fraudulent collections, ideally dedicating some or all the savings to deficit reduction.

The ERC was originally established in the March 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) to incentivize, encourage and support employers to keep their workers on payroll during the pandemic by providing a refundable tax credit of up to $5,000 per employee, effective through the end of 2020. The original credit was offered as an alternative to accepting loans through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). After initial uptake was slower than expected, lawmakers expanded the credit in the Response & Relief Act, to up to $14,000 per employee and businesses who lost 20 percent of revenue as opposed to 50 percent under the CARES Act, allowed businesses with PPP loans to claim the credit, and extended it through June 2021. The ERC was once again extended through the end of 2021 in the American Rescue Plan, making the maximum allowable credit up to $28,000 per employee, though the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law ended the ERC as of September 2021. Although the credit only applied to payroll between March of 2020 and September of 2021, businesses have until April 15, 2025 to apply.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and Congressional Budget Office estimated that the original ERC would cost $55 billion. Thanks to extremely low uptake of the credit, they estimated a much lower cost of extensions, and a total combined cost of roughly $78 billion. As of summer of 2021, estimators thought the actual cost would come in much lower.

However, take-up rates increased when ERC eligibility opened up to PPP borrowers and especially when third-party ERC promoters started raising awareness of the credit and offering to file for the credit on behalf of businesses, in exchange for a cut. In addition to promoters exploding the take up rate, the credit seems to have become highly susceptible to fraud due to the self-attestation component and the limited time and resources the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) had to review for mistakes.

In September of 2023, the flood of applications became so large that the IRS ordered an immediate stop to processing claims.

Using data from the IRS and elsewhere, Donald Schneider of Piper Sandler has estimated the ERC added around $230 billion to the deficit through FY 2023 and will cost over $550 billion in total if action isn’t taken to prevent further applications. This includes $240 billion still being processed and another $70 billion of further applications that would continue through April of 2025.

The IRS has since taken some steps to combat fraud including educational campaigns to identify scams, disclosure programs to withdraw filed claims with little penalty, and a moratorium on processing new claims. However, legislative actions would be needed to truly stem new costs.

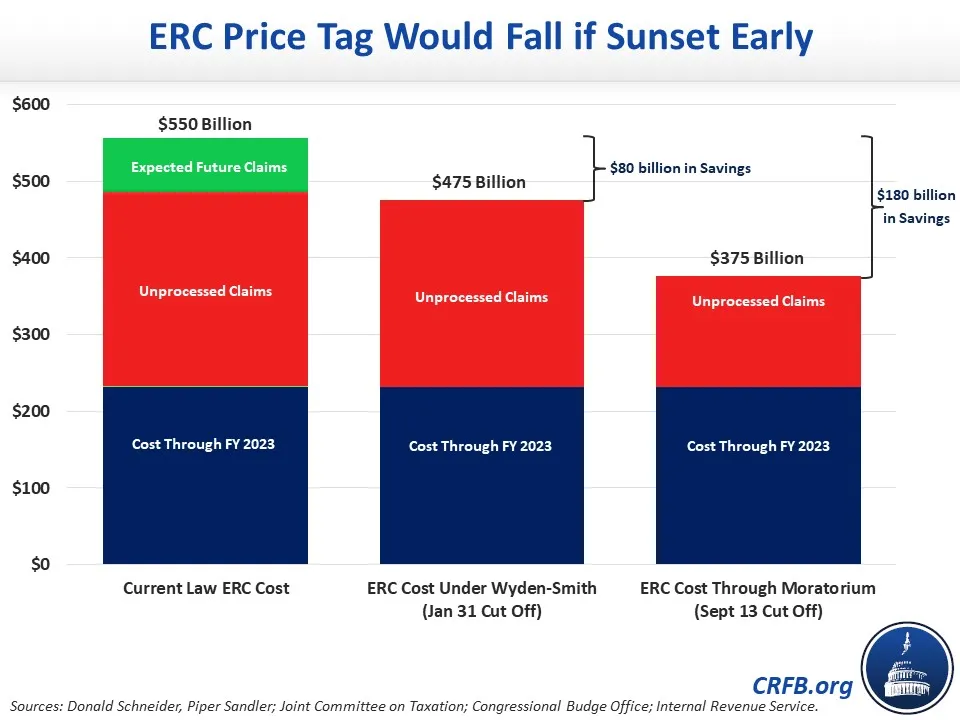

The recently proposed bipartisan Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act of 2024 (Wyden-Smith) would reduce the cost of the ERC by $79 billion. This would come mostly from cutting off new applications for the credit on January 31, 2024, rather than the current end date of April 15, 2025. Additional savings would come from reducing fraudulent claims, including an increase in financial penalties on promoters for aiding and abetting in tax fraud and an increase in disclosure requirements.

Lawmakers could generate additional savings by cutting off applications retroactively. For example, Donald Schneider has estimated that ending applications at the time of the moratorium – September 14, 2023 – would increase savings to roughly $180 billion. Very few businesses who applied this late in the process – a year and a half after the beginning of the pandemic – need these funds for its originally intended purpose. Additional savings could be achieved by ensuring the IRS is adequately funded and has adequate time to review and process claims; cutting IRS funding is a step in the wrong direction.

Ideally, much of the savings from ending these excessive payments would go toward deficit reduction, especially in light of massive levels of federal debt. Much more structural tax and spending changes will be needed to truly get the debt under control, but eliminating excessive and unintended payments is a good start.