Defunding Health Care Innovation Jeopardizes the Budget

In a move that could stall promising health care delivery system reforms and drive up entitlement spending, the House Appropriations Committee last week voted to defund the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) in their 2016 Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education bill.

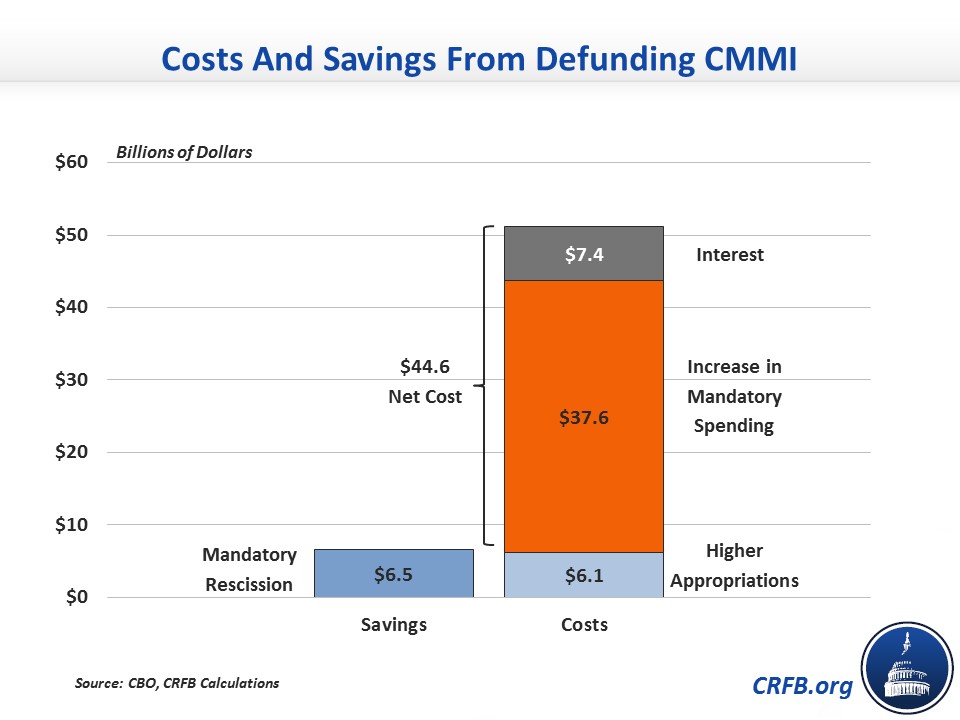

Abandoning CMMI in particular would increase deficits this decade by $45 billion (or by $37 billion before incorporating the additional interest payments needed to service the higher debt), according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and potentially by much more over the long run. The Innovation Center, created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is in charge of testing new approaches to improve quality and reduce cost within Medicare and Medicaid, including promising programs such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), bundled payments, and initiatives to increase care coordination among low-income seniors and people with disabilities who are dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Rescinding CMMI’s remaining $6.8 billion ($6.5 billion of outlays) in funding through 2020 (funding beyond 2020 is not eliminated) would put these initiatives and many more in jeopardy or delay them significantly, and severely curtail CMMI’s ability to fine-tune them as time progresses. Moreover, they would no longer be able to undertake new delivery system reform efforts with the potential to improve quality and lower costs, which is part of the reason CBO finds that defunding would increase mandatory federal health care spending by about $37 billion over the next ten years.

The rescission also represents an egregious budget gimmick, and is perhaps the worst CHIMP (change in mandatory program) we have seen so far. As we’ve explained before, CHIMPs allow policymakers to cut mandatory spending in order to pay for discretionary spending increases. More often than not, the discretionary spending increases are real, but the mandatory cuts are fake – and for one reason or another do not generate actual savings. In this case, the situation is far worse – rather than failing to generate savings, this CHIMP creates significant future costs.

Specifically, this CHIMP allows Congress to spend $6.2 billion of savings ($6.8 billion of rescissions minus $0.6 billion of costs) from FY2016, while ignoring the $37 billion increase in deficits over the subsequent nine years. The result is $45 billion of net new costs over a decade – $6 billion on the discretionary side, $31 billion on the mandatory side, and over $7 billion more in interest payments. The mandatory spending costs of this change should be reflected on the pay-as-you-go scorecard and thus require offsets.

With fast-rising health care costs a key detriment both to the economy and our nation’s fiscal future, CMMI’s ability to experiment and innovate is desperately needed, particularly as evidence grows that delivery system reform changes are playing a role in the recent cost slowdown. In fact, there’s a strong case that our delivery system efforts should be reinforced and made stronger, rather than rolled back.

CMMI’s flexibility to hone its approaches over time provides an additional benefit and “increases the likelihood that a model tested by CMMI will be successful in either reducing spending without harming the quality of care or improving quality of care without increasing spending,” according to CBO. For this reason, CBO actually finds that a House bill to start a new demonstration outside of CMMI to allow value-based insurance design in Medicare Advantage (MA) would result in lower savings than the comparable model that CMMI was likely to undertake. Therefore, CBO estimates that the House bill would actually increase Medicare spending by $210 million over ten years.

Further hampering health care reforms, the House bill also defunds AHRQ, which funds valuable health services research and produces important data like the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, detailing how Americans use and pay for health care. Learning what works and what doesn’t in health care delivery is critical to creating a sustainable health system that provides high quality, affordable care.

To bring health care costs under control while delivering high-quality care, institutions like CMMI and AHRQ that can foster innovation are critical resources that should not be abandoned without a viable alternative.

Such a move seems particularly odd in the wake of the overwhelming bipartisan support behind the recent Sustainable Growth Rate replacement legislation, which provided an important boost for the efforts to promote alternative payment models underway at CMMI. Why encourage such delivery system reforms with one hand while stunting their development with the other?