CBO Takes a Look at the Distribution of Taxes and Transfers

On Monday, we took a look at the breakdown of federal spending and taxes by the type of household, particularly between elderly and non-elderly households. But CBO's recent analysis of 2006 household data also contains valuable information on the income distribution of the budget as well. CBO excludes elderly households from this analysis as market income is not a good measure of their resources -- they rely instead mostly on retirement savings, Social Security benefits and pensions -- but the report still provides useful insight into the effect of taxes and transfers on the overall income distribution.

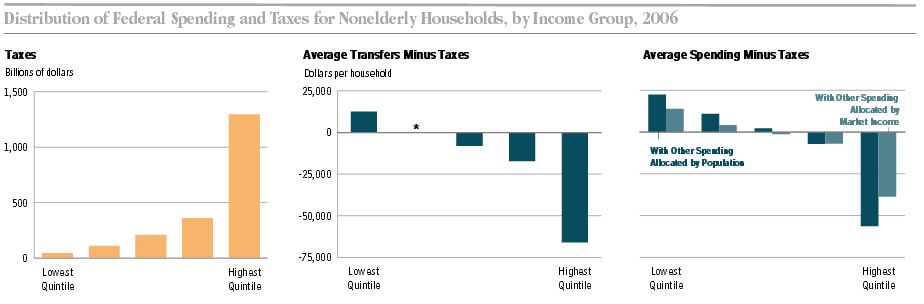

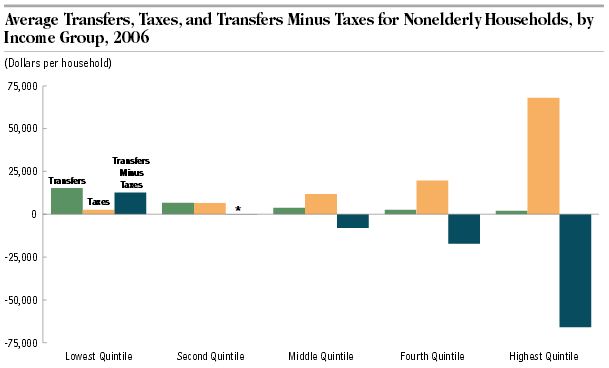

For non-elderly households, the lowest income quintile receives about $13,000 in net transfers after taxes, while the top three quintiles, particularly the top quintile, paid more taxes than they received in transfers. When government spending other than transfers is included, the bottom two quintiles are shown to benefit, the 3rd and 4th quintiles roughly break even, and the highest quintile pays more in taxes than it receives in benefits.

One noticeable finding from CBO's report is how much of the progressivity of the federal budget is the result of the tax code. For nonelderly households, transfers are progressive, with lower income households receiving a larger share, but the tax code's effect on distribution is far larger. Of course, including elderly households would again change the distribution, as would including the activities of state and local governments. Internationally, America has a very progressive tax code since most other industrialized nations have some form of sales tax, but transfers are less progressive than in many other industrialized nations.

Lawmakers ultimately need to decide what combination of taxes and transfers is best for achieving the progressivity they desire. But one myth that is counterproductive is the idea that deficit reduction plans will hurt low income households and make income distribution more regressive. As we've shown on this blog, many plans have adopted the Fiscal Commission's principle of instituting reforms that protect low-income households. The Bipartisan Path Forward, a plan Erskine Bowles and Al Simpson released in March, contained many low-income protections, such as a repeal of sequestration and an including old age "bump up" with their chained CPI proposal, similar to the policy included in the President's Budget.

Tax reform can also be progressive, as many of the tax expenditures in the code disproportionately benefit wealthier households. Many of these provisions, if not eliminated, could be redesigned to be more progressive and cost less, for example, by turning deductions into credits.

Protecting the disadvantaged in a comprehensive deficit reduction is one of the enduring legacies of the Fiscal Commission and one that the budget conferees should follow. Not all of the budget options released in CBO's report may hold lower-income households harmless, but they can easily be modified to do so. Morever, what ultimately matters is the overall effect of a plan, and a comprehensive plan is better positioned to make lower-income people better off overall. Lawmakers will need to make tough choices, but if they are committed to protecting the disadvantaged, it is definitely achievable.