CBO Analyzes the Economic Effects of Waiting to Fix the Debt

Waiting to address our high and rising national debt has substantial adverse consequences. High debt slows income growth, increases interest payments, places upward pressure on interest rates, weakens our ability to respond to the next recession or emergency, places an undue burden on future generations, and increases the risk of a fiscal crisis. In a recent report, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) examined the economic effects of implementing two illustrative policy options in 2026, 2031, and 2036 to stabilize debt as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In each scenario, CBO assumed the policy change would be announced immediately and people would adjust their behaviors in anticipation.

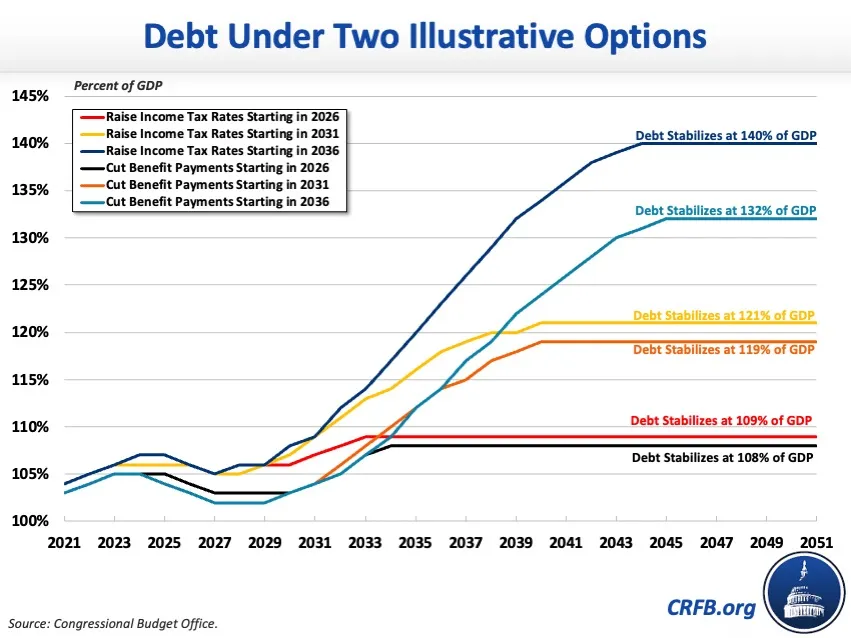

The first illustrative option CBO examined was a gradual increase in the personal income tax rates on labor income and capital income in proportion to the tax rates that were in effect for tax year 2021. CBO found that debt would stabilize at 109 percent of GDP by 2033 if the policy change were implemented in 2026, at 121 percent by 2040 if the change were implemented in 2031, and at 140 percent by 2044 if the change were implemented in 2036.

The second illustrative option was a gradual cut in benefit payments, which assumed Social Security benefits and federal spending on the major health care programs – Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the exchanges – would be cut proportionally to each program’s share of total government spending. CBO found that debt would stabilize at 108 percent of GDP by 2034 if the policy change were implemented in 2026, at 119 percent by 2040 if the change were implemented in 2031, and at 132 percent by 2045 if the change were implemented in 2036.

CBO found that waiting to stabilize debt-to-GDP through personal income tax rate increases would ultimately reduce the size of the capital stock and the labor supply, after-tax wages, consumption, the after-tax rate of return on private savings, and economic output. Specifically, CBO found that delaying the personal income tax rate increases until 2031 would reduce the size of the capital stock in 2051 by 1.5 percent and the size of labor supply by 0.4 percent compared to increasing taxes in 2026. Delaying them until 2036 would decrease the capital stock by 4.0 percent and the size of labor supply by 1.7 percent.

After-tax wages in 2051 would be 2.1 percent lower with a five-year delay and 9.5 percent lower with a ten-year delay, while consumption would be 0.5 percent and 2.5 percent lower, respectively. The after-tax rate of return on private savings would be negligibly affected by a five-year delay but would increase by 0.2 percentage points in 2051 with a ten-year delay.

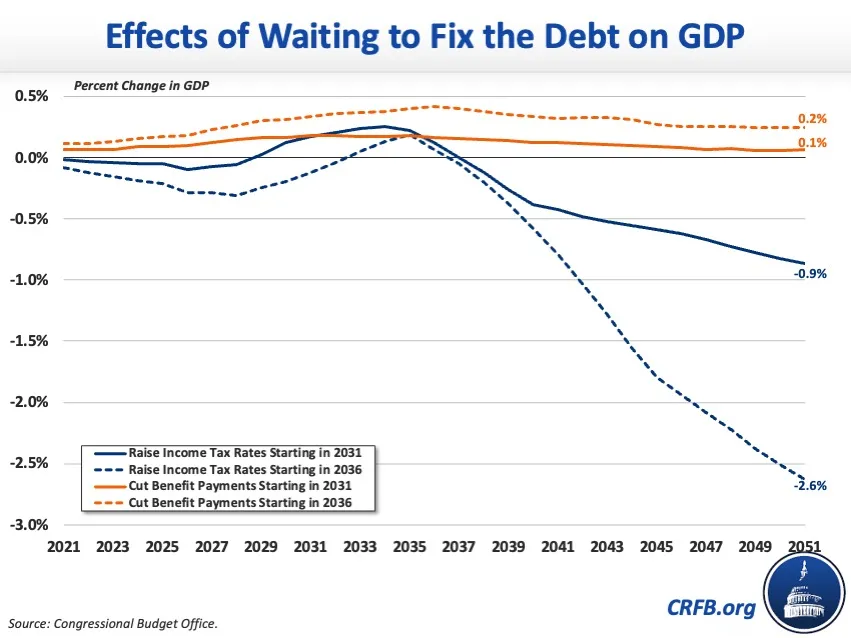

Regarding economic growth, CBO found that if policymakers raised income tax rates to stabilize debt at 121 percent of GDP beginning in 2031, economic output in 2051 would be 0.9 percent lower. On the other hand, stabilizing debt at 140 percent of GDP by raising income tax rates beginning in 2036 would reduce 2051 GDP by 2.6 percent.

On the other hand, CBO found that waiting to stabilize debt-to-GDP by reducing Social Security benefits and health care spending would ultimately decrease the size of the capital stock, after-wages, and consumption but would increase the size of the labor supply, the after-tax rate of return on private savings, and economic output. Specifically, CBO found that delaying the benefit reductions until 2031 would reduce the size of the capital stock in 2051 by 0.1 percent, after-tax wages by 0.3 percent, and consumption by 0.1 percent. Delaying the policy change until 2036 would reduce after-tax wages in 2051 by 0.6 percent, consumption by 0.2 percent, and would negligibly affect the size of the capital stock.

The after-tax rate of return on private savings would be negligibly affected by a five-year delay but would increase by 0.1 percentage points in 2051 with a ten-year delay. CBO found that if policymakers cut benefits to stabilize debt at 119 percent of GDP beginning in 2031, economic output in 2051 would be 0.1 percent higher. On the other hand, stabilizing debt at 132 percent of GDP by cutting benefits beginning in 2036 would increase 2051 GDP by 2.2 percent. The size of the labor supply would ultimately increase by 0.2 percent with a five-year delay and by 0.4 percent with a ten-year delay because a decrease in benefits would reduce people’s incomes and incentivize them to work more to maintain their standard of living.

CBO’s estimates were made using its life-cycle model of the economy that assumes people base their decisions on how much to work and to save on current economic conditions and government policies, as well as their expectations of future conditions and policies. Therefore, CBO's estimates reflect the way in which people respond, on average, to economic and policy changes. In addition, the model assumes that the increase in debt from larger budget deficits increases the interest rate on government debt because higher deficits and debt crowd out private investment.

Importantly, CBO’s estimates are subject to uncertainty because they reflect the way in which people have responded to policy changes in the past, which does not necessarily indicate how people will respond to future policy changes. Moreover, they do not account for two key effects waiting to fix the debt would have: less available fiscal space for the federal government to respond to the next recession or emergency and an increased risk of a fiscal crisis. In addition, any event that pushes the economy into a recession could dramatically affect debt-to-GDP and other economic factors not considered in CBO's analysis.